Why is Dedicated Funding Needed Today?

Managing flooding and building and maintaining stormwater infrastructure are not new components of most cities’ public works programs.

However there is a growing need to ensure adequate and reliable funding streams are available at the municipal scale to reduce increasing street flooding, basement back-ups, as well as erosion, contamination and degradation of rivers and lakes, which arise from inadequately managed stormwater. Today many municipalities in our region face a triple threat with regard to stormwater management:

- Increasing impervious surfaces—think hard surfaces such as roads, driveways, parking lots and rooftops—which repel rainwater, sending increasing amounts of runoff to our storm sewers;

- Existing stormwater infrastructure that is under-sized, not-well maintained and/or fast approaching the end of its useful life; and

- Frequent and more intense rain events, which are expected to increase.

The Illinois State Water Survey recently released a report that projects the frequency of extreme rainfall events out to the year 2100 in Cook County based on impacts of future climate change. The underlying findings are that heavy rainfall events are expected to increase. And a federal survey in 2008 found that municipalities in the Chicago region had a stormwater management funding backlog of $233 per household.1 As storms increase in severity, and as infrastructure continues to age, the costs for effective stormwater management is expected to increase. Robust stormwater programs with dedicated sources of revenue are needed to address these urgent challenges.

Costs of urban flooding

A report from the Center for Neighborhood Technology examined flood damage in Cook County, Ill. between 2007 and 2011. The study found that insurance claims paid out for the five-year period amounted to more than $773 million.

Where will the money come from to fund capital projects, and system operation and maintenance? Public utilities such as electricity, natural gas and telecommunications fund capital projects, operation and maintenance, by charging users a fee. Likewise, customers pay user fees for drinking water and wastewater services.

For years we have treated stormwater differently. Although stormwater systems provide a service—they help prevent street flooding, basement back-ups and pollution—stormwater programs and infrastructure needs have very often not been funded by a dedicated revenue source. This trend is changing throughout the country, as municipal leaders are considering ways to establish dedicated funding to attend to their communities’ stormwater challenges.

The purpose of this guide is: to identify what avenues are available for municipalities to reliably and consistently generate adequate funds to manage stormwater.

Deferring maintenance is not a sustainable solution

If maintenance activities are scaled back due to insufficient budgets, facilities and equipment can break down, causing problems such as property damage, street flooding and emergency repairs. The National Research Council has found that each $1 “saved” by deferring maintenance and repair work results in a long-term capital liability of $4 to $5.

To compile this guide, we combed through national and regional reports, surveys and other source materials. First-hand interviews with knowledgeable stormwater managers can be found in the case study section of this resource. A variety of options are profiled, and communities can select and tailor the option(s) most suitable for their circumstances. While MPC generally encourages communities to consider setting up a dedicated revenue stream for stormwater, that may not be suitable for underserved communities with limited financial capacity which would most likely require outside, additional resource assistance.

Given the triple threat facing communities in our increasingly wet, rainy region, having a steady stream of revenue available for stormwater services is critical. Read on to learn what kind of funding streams other local units of government are establishing today to protect their communities.

What are some dedicated revenue options?

There are several ways for municipalities to generate dedicated funds to support operation and maintenance, and finance stormwater projects. What’s more, once established, dedicated funds can be leveraged to raise additional capital for infrastructure projects. Following are some of the approaches U.S. communities are using today.

General versus dedicated funds

Municipalities commonly fund and finance their stormwater-related infrastructure projects through their general funds. General fund budgets are supported by revenue from taxes (property, sales and/or income taxes), franchise fees paid by utilities, and federal/state revenue sharing. These funds are appropriated to address a wide variety of community needs through municipal budgeting processes. General funds may provide sufficient revenues for stormwater management in municipalities with limited stormwater needs. However, in many situations the general fund approach is inadequate or inconsistent. That’s because the stormwater program often competes with other city departments to access finite general fund dollars, and stormwater needs can be short-changed. Eventually inadequate stormwater budgets manifest in the form of emergency repairs (which always cost more than routine maintenance), flooding and/or water pollution.

Dedicated tax

One way to ensure that stormwater needs have a steady stream of revenue is to establish a dedicated tax. The taxes collected are then used exclusively for stormwater solutions. This approach generates dollars through a levied municipal sales tax, but earmarks the funds for stormwater projects, thus guaranteeing long-term funding.

Stormwater fee

An increasingly popular funding strategy is the adoption of stormwater fees. These types of fees are often referred to as a stormwater utility fee or a stormwater service fee. A steady stream of revenue is generated through a user fee assessed to property owners, and the revenues from the stormwater charges go into a discrete fund that may only be used for stormwater projects and services (including management, operation and maintenance). A key distinction is that the money paid into the fund is a fee for service and not a tax.

In many cases, communities form a stormwater utility to manage the revenue collected and be responsible for stormwater infrastructure and services. A stormwater utility is to stormwater what a public water supply utility is to drinking water—it is a stand-alone service unit supported by fees. In other communities, fees are collected and deposited into a dedicated stormwater fund and stormwater projects and services are managed by the city engineering department or the department of public works.

| Year |

Number of stormwater utility fee systems |

| 2010 |

1,112 |

| 2013 |

1,412 |

| 2016 |

1,583 |

Source: Data from the 2010, 2013, and 2016 Western Kentucky University’s Stormwater Utility Surveys

Survey work done by Western Kentucky University identified almost 1,600 communities in the U.S. and Canada which have fees for stormwater infrastructure and services through a dedicated fee system. Most of these communities have stormwater utilities. Thirty-nine states have one or more community with a dedicated stormwater fee. Seven states have 100 or more stormwater utilities. Minnesota, Wisconsin, Iowa and Ohio have significantly more communities collecting dedicated stormwater fees than does Illinois.2

The fees charged are often based on how much impervious area there is on a property or how much stormwater is estimated to run off a property. Many communities include a credit program as a component of their fee system, which lowers the fee charged based on site improvements such as rain gardens or cisterns or detention features that reduce the amount of stormwater running off a property during a storm. With a stormwater fee in place, a community can improve its stormwater infrastructure through dedicated funds generated in an equitable manner.

Special assessments/special service areas

Special service areas in Illinois

Under Illinois law, Special Service Areas (SSAs) can be created in both home-rule and non-home-rule units of local government. For home-rule municipalities, the Illinois Constitution provides that the municipality may “levy or impose additional taxes upon areas within their boundaries in the manner provided by law for the provision of special services to those areas and for the payment of debt incurred in order to provide those special services.” (Illinois Constitution, Article 7, §6 (l)(2).)

Non-home-rule municipalities “shall have only powers granted to them by law.” (Illinois Constitution, Article 7, §7.) This is generally thought to include having the power to impose additional taxes/fees on areas receiving the provision of special services.

Special assessment is a term used to describe specific charges that governmental units can levy certain real estate parcels for public projects or services. This charge is levied in a specific geographic area frequently referred to as a special service area. A special assessment is charged to owners of parcels identified as receiving a direct and unique benefit from particular public facilities or infrastructure. Special assessments can pay for new or improved infrastructure projects (capital projects), and/or for the operation and maintenance of facilities/ infrastructure. Multiple special service areas can be formed within a municipality, when discrete facilities/infrastructure benefit different community areas.

Special assessment charges may be seen by residents and businesses as being equitable, since only residents who benefit from such developments are asked to pay for them. Additionally, because residents and business owners in a particular community may be acutely aware of local flooding issues, they are often willing to pay a stormwater fee, because of the direct connection between the benefit of such projects and their cost.

Special assessments are best used for local capital improvement projects and for the operation and maintenance of facilities/infrastructure that benefit a specific area. For example, if a community needs to construct new storm sewer lines and a detention basin for an industrial park, and then subsequently operate and maintain these infrastructure elements, it may make sense to designate the industrial park as a special service area.

How can stormwater funds be leveraged?

By establishing dedicated stormwater management funding, municipalities are able to proactively finance infrastructure projects to reduce the impacts of flooding. Following are some examples of how a community can leverage its dedicated revenue source to finance stormwater capital improvement projects.

Municipal bonds

A municipal bond is a bond issued by a local unit of government to pay for public projects such as roads, schools, and water, wastewater and stormwater infrastructure. Bonds are not a revenue source; they are a means of borrowing money. Bonds allow expenditures—such as capital improvement projects for stormwater management—that exceed a local government’s annual resources.

If a community is considering issuing bonds to pay for stormwater infrastructure projects, it must evaluate how much money is needed over what time period, and identify how the bond holders will be paid. Municipal bonds may be set up as general obligations of the issuer or secured by specified revenues. Either way, the community must have a reliable stream of future incoming funds to demonstrate its ability to pay back its investors.

State revolving funds

Another means of financing a stormwater infrastructure project is a low-interest loan from the State Revolving Fund (SRF). Through its Clean Water SRF, a State can obtain low-interest loans for wastewater and stormwater projects which help protect and improve water quality. If a community in Illinois wishes to apply for a SRF loan, the Illinois Environmental Protection Agency requires the submission and approval of a complete financial package including a dedicated revenue stream that is adequate to assure loan repayment. Thus, similar to municipal bonds, having an established revenue stream is necessary for a community considering an SRF loan to raise capital for crucial infrastructure projects.

Community-based public-private partnerships

In addition to bonds and loans, communities also can consider establishing public-private partnerships (P3s) to finance needed stormwater infrastructure improvements. This approach engages the private sector in funding infrastructure projects to meet public service needs. P3s involve the private sector in financing, planning, design, construction, operation, maintenance and/or rehabilitation and replacement of publicly-owned infrastructure.

With P3s, a community typically maintains ownership and ultimate responsibility of any infrastructure, however the private sector is brought in to help finance projects and/or improve cost efficiencies for construction and/or operation and maintenance. P3s may allow for increasing the ability to leverage public funds while minimizing impacts to a municipality’s debt capacity. Like the other financing tools described, P3s require a dedicated revenue stream for repayment.

Case studies

The following section features some useful case studies of communities that have been successful at implementing a dedicated revenue stream, and seen improvements to stormwater conditions for residents and businesses.

Westmont, Ill.

Steady stream: Stormwater management sales tax

Highlight: Involving community members in developing solutions

The Village of Westmont is a northeastern Ill. community with a population of about 25,000. After major flooding events in April 2013, the Mayor of Westmont asked residents to come forward to discuss flooding impacts. One month after the April floods, the community was invited to talk about the hardships they faced due to flood damages. Larry McIntyre, Westmont communications director, took the lead as project manager. Westmont officials listened to the residents and businesses, and recognized substantial stormwater management improvements would be needed. A month after the initial community meeting, Larry and his team set up a stormwater committee comprised of 14 residents which was advised by Village technical/engineering and finance staff. The committee was tasked with working on solutions to the flooding problems. The committee worked diligently on the issues, and the committee and Village leaders eventually came up with six options to raise revenue for stormwater management, including Special Service Areas, stormwater utility fees and a dedicated sales tax.

The Village initially leaned in the direction of a 3-tier user fee system. Through public engagement, Larry and his team discussed the pros and cons of a fee versus a sales tax. Momentum built within the Village for the sales tax option. Many found the utility fee methodology too confusing, and this approach was also viewed by some as being too costly for businesses. A sales tax provided administrative advantages for the Village, as the tax would be paid along with other sales taxes, with the funds initially routed to the State and then paid to the Village in regular installments.

A referendum was held in April 2015. To encourage voter understanding and participation, the village came up with a slogan: “a vote ‘no’, supports the status quo”— the status quo being continued flooding with no solution. The 0.5% Stormwater Management Sales Tax was passed by voter approval, and the Village began collecting the tax on July 1, 2015. It is projected that the sales tax will generate more than $750,000 each year. These funds will be used to pay for stormwater improvement projects.

The sales tax is imposed on a seller’s receipts from sales of tangible personal property for use or consumption. Tangible personal property does not include real estate, stocks, bonds or other ‘paper’ assets. Westmont car dealerships are not subject to the stormwater sales tax, so as not to encourage car-buying in other jurisdictions.

Back to cases

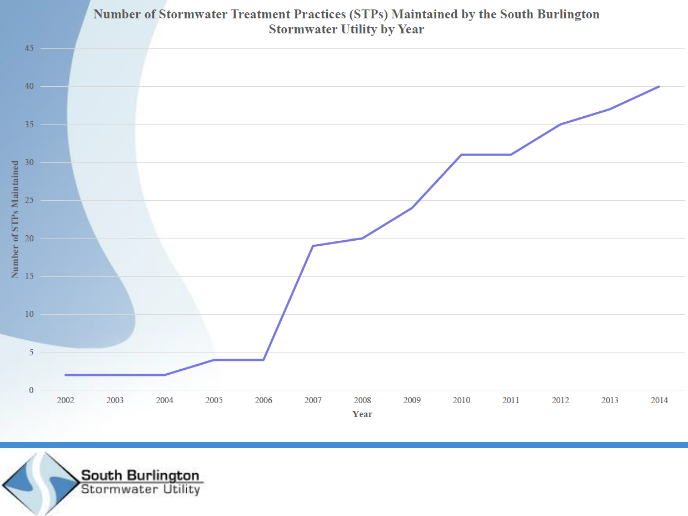

South Burlington, Vt.

Steady stream: Stormwater utility fee

Highlight: Keeping up with regulatory requirements

South Burlington is a community located on the shore of Lake Champlain, with a land area of approximately 16.6 square miles and a population of about 18,600. Stormwater infrastructure includes more than 6,268 catch basins and 177 miles of pipe. The City has been subject to some significant water quality requirements to restore and protect Potash Brook, Bartlett Brook, Centennial Brook, Munroe Brook, Englesby Brook and Lake Champlain, and has been building and maintaining an increasing number of stormwater control measures.

“In its first 10 years, the South Burlington Stormwater Utility has successfully completed over 20 stormwater treatment projects within the City. We will likely need to construct an additional 100+ projects over the next two decades in order to meet water quality standards in our watersheds. As an MS4 community we pair local dollars raised through our stormwater utility with the State and Federal grant funding, which is critical to the economic viability of our implementation process,”

—According to South Burlington Public Works’ Assistant Stormwater Superintendent, David Wheeler.

Photo: South Burlington

The City sewer ordinance was updated in March 2005 to establish a stormwater utility fee. Stormwater fees were first assessed in April 2005. Revenues produced from the fees collected are used for:

- Stormwater infrastructure operations

- Capital improvements

- Maintenance

- Storm drain cleaning

- Street sweeping

- Stormwater treatment practices

- Finding and eliminating illicit discharges

- Public education and outreach

- Watershed planning

- Technical assistance

- Plan review (stormwater aspects)

The stormwater fee paid by any single family residential property is a flat rate of $6.54 per month, while non-single family residential properties pay a fee based on the amount of impervious area relative to the impervious surface of an average single family residential parcel. By installing stormwater treatment practices in accordance with the State of Vermont Stormwater Management Manual, a commercial property owner can receive credits to reduce its fees by up to 50 percent.

South Burlington Stormwater Services maintains a webpage with information on key projects planned or underway for community members to see what progress is being made. Having a dedicated revenue stream has enabled the municipality to consistently carry out needed operation and maintenance functions as well as new projects to help restore and protect its valuable water resources.

Back to cases

Highland Park, Ill.

Steady stream: Stormwater utility fee

Highlight: Funding and implementing projects can reduce citizen hardships

The City of Highland Park, with a population of almost 30,000, is located on the western shore of Lake Michigan and has areas that drain to three watersheds. The initial motivation for a stormwater utility fee was a number of major flooding events in 2001 to 2002. Aging and sometimes undersized storm sewer infrastructure contributed to flooding in Highland Park, and the City’s storm sewers in many places did not have capacity to capture and convey a 10-year storm event.

Valued results!

Before the implementation of the stormwater utility fee and the full implementation of maintenance and upgrades to storm sewers, public works would receive 200-300 calls during and after a flood event. Today the City receives very few calls following a 6-inch/24 hour rain event.

The City of Highland Park adopted a stormwater management fee in 2006. Support for the fee was driven by the need to fund stormwater operating and capital expenses, and to address water quality and flooding issues without having to increase property taxes. As of 2016, revenues from the stormwater management fee contributed to 45 percent of the Sewer Fund that pays for infrastructure upgrades. The plan has been in place for the Sewer Fund to pay for 100 percent of operating and capital costs with revenues collected from the stormwater management fee as well as other fees. A yearly average of approximately $1 million is budgeted for the City’s storm sewer maintenance and stormwater projects.

2016 Sumac Road storm sewer upgrade project construction largely funded by the City's stormwater management fee.

Photo: City of Highland Park, Ill.

The stormwater management fee is collected based on impervious area of properties, with 2,765 sq. ft. of impervious surface area equaling one impervious area unit. The fee appears on the water bill. The City offers a credit for properties, commercial or residential, that detain and treat their stormwater prior to discharge to the City storm sewer. Such properties may be eligible for a 25 percent credit.

Ramesh Kanapareddy, director of public works, provided information regarding progress resulting from the stormwater infrastructure and operational improvements that have been completed using revenues from the fee system. Before the implementation of the stormwater utility fee and the full implementation of maintenance and upgrades to storm sewers, on an average Department would receive 200 to 300 calls during and after a heavy flood event. Today, the City receives few calls following a six-inch/24-hour rain event, and 10-year storm events are handled with the upgrade of storm sewers. This is a huge win for the community and shows the benefit of comprehensive maintenance and strategic stormwater projects. These kinds of results have led to a growing acceptance of the stormwater utility fee.

Back to cases

Rolling Meadows, Ill.

Steady stream: Stormwater management fee

Highlight: Leveraging capital through a stormwater fee

A stormwater project under construction

Photo: Rolling Meadows Department of Public Works

The City of Rolling Meadows is located in northeastern Ill. and has a population of about 24,000. The City first implemented a stormwater management fee in 2001; the fee system was instituted via ordinance after severe flooding events that year. Simultaneous with the establishment of the fee system, the City created a Stormwater Management Fund to which fees collected were directed, and an accounting system was set up to track all expenditures for stormwater maintenance and capital projects. A bond for stormwater projects and services was issued in 2002. Revenue from the stormwater management fee is used to pay off the bond and to operate and maintain the City’s storm sewer infrastructure.

According to Fred Vogt, public works director for the City of Rolling Meadows, the first successful projects using funds generated by leveraging the stormwater fee revenues were implemented between 2003 and 2005 when the City completed two large stormwater drainage projects. The City offers a Rear Yard Drainage financial assistance program for private property owners that provides up to 50 percent in matching funds to correct drainage problems if a utility easement or drainage easement is provided. Rolling Meadows is planning a Salt Creek Park District Partnership to create stormwater storage detention systems and new storm sewers to limit or eliminate flooding in affected areas near South Park. The engineering designs are underway for this City and Park District collaboration.

Although Rolling Meadows does not have formal metrics for measuring the success of stormwater fee-funded projects, the City notes that since storm sewer system improvements began in 2002 several neighborhoods no longer experience flooding despite several heavy rainfall events that took place in 2007, 2008, 2011 and 2013.

Back to cases

Northbrook, Ill.

Steady stream: Stormwater utility fee

Highlight: Funding and implementing projects can reduce flood insurance costs

The Village of Northbrook, Ill., with a population of over 33,600, has seen an increasing incidence of major flood events over the past decade. To address stormwater and flooding issues, the Village’s Stormwater Management Commission, staff and the Village Board contributed to a Master Stormwater Management Plan completed in August 2011. The plan initially included 22 public infrastructure projects intended to reduce flooding impacts. An addendum to the plan in April 2012 added another six projects, and an April 2015 plan update added three more, bringing the total to 31.

The Village established a utility fee in 2011 to generate funds for stormwater management and maintenance. The utility fees fund three main components: operation and maintenance costs; capital improvements; and paying off debt service for bonds issued to fund stormwater management projects. Additionally, some projects have received grants to help fund costs.

Mr. Kelly Hamill, director of public works for Northbrook, highlighted two projects that have provided tangible benefits in terms of reduced flooding and reduced flood insurance costs. The Techny Drain project provided additional capacity for stormwater. The project was carried out in four phases and was completed in 2012. With the success of this project, 15 properties that were once in a flood zone, per the Flood Insurance Rate Map, will no longer be in a flood zone. This will reduce flood insurance costs for property owners.

Wescott Park project under construction

Photo: Village of Northbrook

The Wescott Park project consists of constructing a new storm sewer to supplement the existing sewer and construction of a stormwater chamber underneath the northern half of the park. The chamber will be able to hold about 7.5 million gallons of water. Together with the new storm sewer, the project will improve flood protection, controlling rainfall from all storms up to a once-in-25-years storm. This is a significant improvement from the currently estimated once-in-five-years storm (a much smaller storm size). The stormwater chamber will include a rainwater harvesting system, which will enable the Village and the Park District to reuse water captured during rain storms. A total of 91 properties will see a reduction in property flooding. Twelve of the 91 properties have experienced structure flooding, and the reduction in structure flooding of these 12 properties will be measured over time. The project is a combined effort of the Village of Northbrook, Northbrook Park District and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago.

The Village also maintains a stormwater webpage full of information about the Master Plan and projects planned or underway.

Back to cases

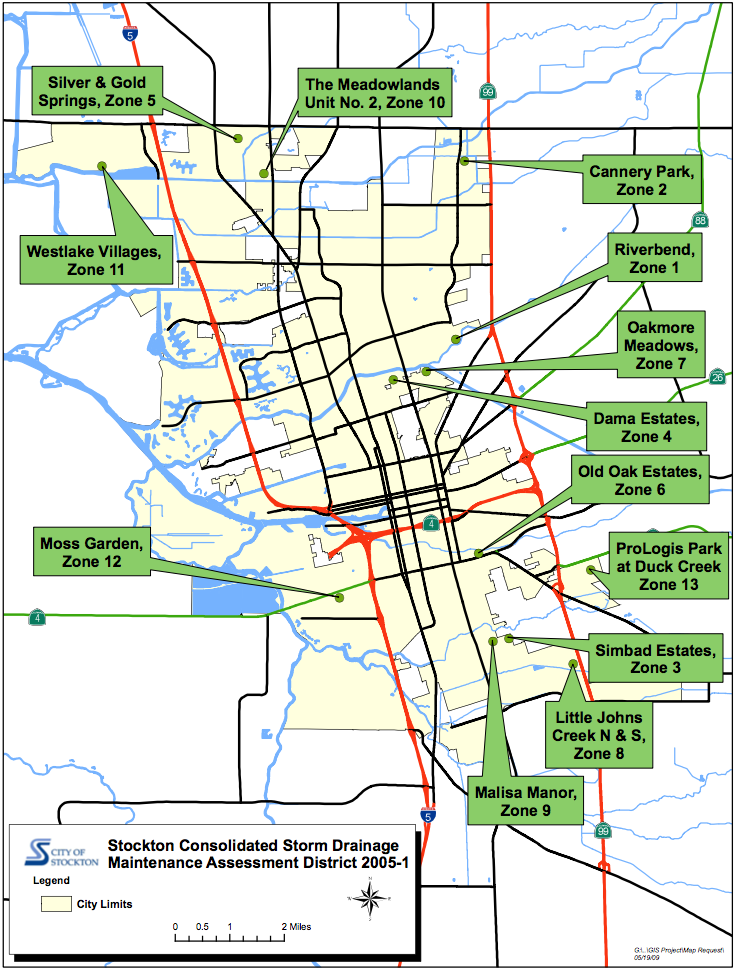

Stockton, Cali.

Steady stream: Special service areas

Highlight: Assessing fees to property owners for stormwater services in their neighborhood

Stockton Consolidated Storm Drainage Assessment District

City of Stockton, Download PDF

The City of Stockton is located in northern Cali. and has population of more than 300,000. In 2005, the Stockton City Council adopted a resolution to establish an assessment district designated as the “Stockton Consolidated Storm Drainage Maintenance Assessment District No. 2005-1” (District) and created the first assessment zone within the District. The formation of this District was based on provisions of the Municipal Improvement Act of 1913 and the Stockton Improvement Procedure Code. The Act and Stockton Code contain provisions for the City to form an Assessment District and annex zones within the District’s boundaries for the maintenance and operation of improvements that provide benefit to a specific area. The purpose of the District is to provide funding for the operation, maintenance and replacement of stormwater quality treatment devices to comply with the City’s Stormwater Quality Control Plan to meet the City’s Stormwater National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System Permit.

The associated annual assessments are collected via the San Joaquin County tax roll with county property taxes. The assessments provide funding for the inspection, operation, maintenance and replacement of the improvements/devices in each zone as well as other administrative costs, including the preparation of an annual engineer’s report and the assessment roll. Property owners are responsible for funding only those improvements within the Zone from which they receive benefit. All fees, costs and expenses incurred to operate the device/zone are paid from the proceeds of the annual assessments levied and collected on the property taxes. The use of the funds collected within the various zones are legislatively restricted by Proposition 218 and are used to pay only the expenses related to the maintenance and operation of the specific stormwater quality treatment device(s) detailed in the engineer’s report for that zone.

Back to cases

Montgomery, Ill.

Steady stream: Special service areas

Highlight: Improving stormwater management through centralized maintenance

A naturalized stormwater basin in Montgomery.

Photo courtesy of Village of Montgomery and Pizzo and Assoc.

The Village of Montgomery Ill., in Kane and Kendall counties, and has a population of more than 19,400. Montgomery has both Special Service Areas (SSAs) and a Special Assessment Area (SAA). The Village points out important distinctions between the two: SSAs are focused on maintenance of stormwater management measures, while an SAA is used to fund infrastructure construction. The Village found there was uneven, sometimes sub-optimal maintenance of stormwater facilities by homeowner associations—this is especially important as the Village requires nearly all stormwater basins to be naturalized with deep rooted prairie plants. By ordinance, the Village established SSAs and through an annexation agreement or HOA dissolution took over management and maintenance of the facilities. This system ensures that necessary maintenance is done on schedule, and allows the cost of a subdivision’s continuing maintenance to be borne by the subdivision itself (rather than the Village as a whole). The assessed amount is added to each property’s tax bill and is only for the cost of the maintenance of the subdivision’s public areas, e.g., stormwater basins. This is an ongoing assessment as maintenance is a continuing cost.

Again, while SSAs are used to pay for maintenance, Special Assessments are used to fund public infrastructure construction costs associated with a particular subdivision. The construction costs are spread out over a number of years and eventually will be paid off. There is just one subdivision in Montgomery that is a SAA.

Back to cases