Flickr user rob (cc)

As any car owner can tell you, delaying maintenance increases the risk of experiencing a larger issue down the road.

By Margaret Schneemann, Water Resource Economist, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant

By Margaret Schneemann, Water Resource Economist, Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant - October 26, 2016

Getting water into our homes and businesses requires a vast distribution system of underground pipes, many of which have been in the ground a long time. Eventually, pipes wear out, causing water leaks and breaks that require repair and replacement.

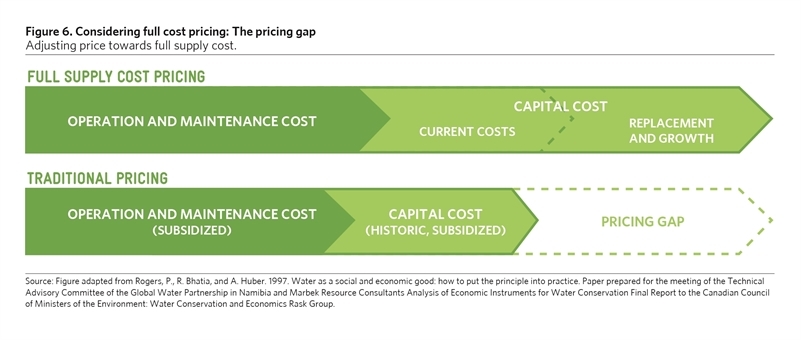

Keeping up with repair and replacement so that we can continue to have reliable and safe water supply means someone somewhere has to pay. While some funding progress has been made in terms of federal programs, as well as making state programs more accessible, the majority of water service funding comes from our monthly water bills. In order to make the needed upgrades to our water pipes and pumps, it will take a shift in the way water is priced—a shift toward full-cost pricing—to comprehensively address water infrastructure needs.

What do I mean by full cost pricing? It’s more than just covering operating expenses. It’s setting a price based on the full economic and social costs of a practice or service—providing drinking water to our homes, businesses and schools for example.

Consider the expenses related to owning and driving your car.

At first glance, it might seem like the cost of driving equals the cost of gas—you put the gas in the car and it goes. But the cost of driving also consists of maintenance fees such as oil changes, tune-ups, tire replacements; other operation costs, such as insurance, registration, parking fees and financing costs; and a lease or car payment or savings you are placing in reserve for your next car. All of these are the direct costs—what economists refer to as the full supply costs, or financial costs—of owning and operating your car.

As any car owner can tell you, ignoring maintenance puts you at risk of experiencing a larger issue down the road that is a lot more expensive to fix than had you proactively invested in maintenance of the car over time.

Beyond these direct costs to car owners, there are societal costs of driving.

These costs include road maintenance and construction costs—paid for directly by drivers through taxes and fees, but also by society, or general taxpayers who may not own a car. Then there are also traffic congestion costs—the longer you spend in traffic, the less time you have to do other things like work or spend time with your family. Economists call these opportunity costs. Another societal cost is emissions—vehicle exhaust, for example, contributes to air pollution and affects our health. Emissions also contribute to the growing concerns about climate change. These costs are known as externalities that society as a whole has to bear the cost of.

Together, these supply costs and societal costs comprise the full costs of driving.

Now apply these cost considerations for water. The supply costs to operate a water utility include all the financial costs of water service: operation, maintenance, administrative costs, any debt service and reserve contributions toward infrastructure reinvestment and replacement. These costs all factor into the cost of water.

CMAP

We need sufficient funds to properly maintain our water systems and keep them in safe, working order. Charging too little for water and delaying maintenance on such an important system puts us all at risk of not only incurring costlier repairs down the line, but also community safety. Not placing sufficient funds into reserves also can compromise a system’s ability to meet ongoing needs.

For many communities here in Illinois, moving toward full-cost pricing will first require closing the gap between current funds recovered from water bills and the full supply cost to provide a safe and reliable service. Common culprits for this gap are:

Fortunately, there are tools to help communities better assess whether or not their current water rate objectives meet the cost needs of operating the water utility—full-cost pricing, affordability, conservation. For example, the Northeast Illinois Water and Wastewater Rates Dashboard allows communities to compare residential water rates against multiple characteristics, including utility finances, system size, customer base demographics and geography. The tool complements a free full-cost pricing manual that can assist communities who want to ensure sustainable water service now and into the future.

Addressing the social costs of water use—costs of water supply planning, conservation programming and water source protection—will, however, require additional policy beyond setting water rates to cover costs.

An important example of the social costs of water use in our region is the potential for communities at risk of running out of groundwater due to aquifer desaturation. If we pull water out of aquifers faster than they are able to be recharged, we’re imposing a cost on future generations left with depleted aquifers and unusable water sources. Economists refer to this as the opportunity cost of water use.

As is the case with direct costs, these and other shared water management challenges can be addressed with sensible policies. For example, water planners can use opportunity cost (or depletion cost) pricing to address water supply and demand imbalances, in conjunction with other policies, including ones addressing the affordability of water service for residents and businesses and carefully considering the location of new water supplies (wells).

When given a choice, residents typically vote in favor of cheaper utility services. Utility governing bodies therefore face the difficult task of balancing the affordability of drinking water with the financial health and long-term sustainability of the water system itself. In order for full-cost pricing to happen, challenges faced by communities implementing full-cost pricing, and ways to successfully motivate communities to adopt full-cost pricing need to be addressed.

The good news is that full cost pricing practices can and should be adapted to consider the many local factors that vary from community to community. When communities understand where their drinking water comes from, and what it takes for water to make it to their tap, it's easier to generate support. Our water supply is not infinite, and cannot be taken for granted. Pricing water rates appropriately in order to ensure sustainable water availability, treatment and delivery in our communities for generations to come is an important step.

Margaret Schneemann is a water resource economist with 20 years’ experience providing research, higher education and outreach. She currently works with the Illinois-Indiana Sea Grant (IISG) program leading projects to create resilient communities and economies in the Great Lakes region.