In 2018 the City of Chicago announced that a notorious metal scrapper would be moving from the north side to the southeast side. After conflicting messages from city agencies, county and federal lawsuits, permit approvals and delays, a health impact assessment, and a nationally publicized hunger strike, the final occupancy permit for Southside Recycling, formally known as General Iron, was denied nearly four years later. The process was controversial, confusing, and reactionary. One reason why? Outdated policy and procedures that haven’t changed in Chicago in decades.

Image courtesy Patrick Houdek, Flickr creative commons

By Jordan Bailly and Christina Harris, Director of Land Use and Planning

By Jordan Bailly and Christina Harris, Director of Land Use and Planning - March 23, 2022

This is the fifth part in a series about yesterday’s policies, today’s challenges, and tomorrow’s opportunities. Follow the links to read parts one, two, three, and four.

In 2018 it was announced that metal scrapper General Iron would be relocating from Lincoln Park on the North Branch of the Chicago River to a site along the Calumet River on the city's Southeast side. After being purchased by Reserve Management Group (RMG) in 2019, the northside facility was closed for good with plans to open a new facility, Southside Recycling, underway. The Chicago Department of Public Health approved the first of two city permits in October 2020, an air pollution control permit, that allowed RMG to begin construction of the new Southside Recycling facility despite significant health concerns from area residents, community organizations, and environmental groups. Ultimately, the second permit was denied earlier this year after RMG spent $80 million building out the new facility at 11600 S. Burley Avenue.

How did we get here? Here’s the story of how activists fought a four-year battle and brought to light the challenges in Chicago’s development review process.

Pre 2018: A problematic history at General Iron

Prior to the announced move, the northside facility was under pressure from a number of interrelated issues. Reaching back to 2015, those issues included a fire, followed by a 2016 city-ordered shutdown, a lawsuit in 2017 for harassment, and a 2018 citation for excessive air emissions. After the 2018 citation, General Iron installed pollution-controlling equipment.

2018-2020: Reserve Management Group buyout, General Iron Closure, and City support

In July of 2018, the City announced that Reserve Management Group (RMG), which operates similar facilities on the southeast side, would acquire General Iron and relocate the operations to a site on the Calumet River. It would later be reported that RMG and City officials under former Mayor Rahm Emmanuel worked together closely on logistics prior to the announcement. Problems at the existing facility continued when explosions in the pollution-controlling equipment forced a temporary closure in May 2020. Within weeks of reopening, and after RMG paid $18,000 to settle previous violations with the city, a scrap pile fire occurred on-site.

The explanation from City and Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) officials that prior non-compliance from General Iron could not factor into permit decisions for RMG and Southside Recycling despite state law that allows for permit decisions to be “specifically related to the applicant’s past compliance history”

2018-2021: Community and residents raise their opposition

Pushback to the proposed relocation was immediate. But, overwhelming opposition during the public comment period in 2020 was met with an explanation from City and Illinois Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA) officials that prior non-compliance from General Iron could not factor into permit decisions for RMG and Southside Recycling. The response from IEPA came despite the previous fires, explosions, city ordered shutdowns and citations, and state law that allows for permit decisions to be “specifically related to the applicant’s past compliance history”.1

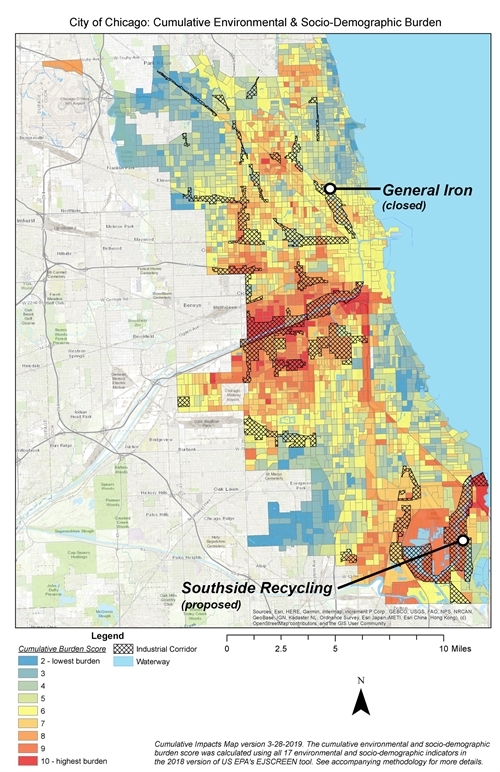

According to an Environmental Justice Map produced by regional organizations, and an air quality report published by the City in 2020, residents in communities around the proposed Southside Recycling facility suffer from some of the worst air quality in Chicago. Over 75 polluters in the area have been investigated for Clean Air Act violations in the last eight years for allowing contaminants to coat residential areas in the surrounding communities.

Figure 1: Cumulative Impact Map courtesy of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Amid ongoing community protest, the Chicago Department of Public Health (CDPH) approved the first of two required permits, an air pollution control permit, allowing RMG to begin construction of the Southside Recycling facility. Let’s note: residents were not informed of the permit approval until 15 days after it was granted, despite promises from city officials to maintain open communication.

In 2021 activists marched through City Hall and the neighborhoods of Mayor Lori Lightfoot and Dr. Allison Arwady (Commissioner of the CDPH) in support of denying the second operating permit. A hunger strike was held in early 2021 and included members from community groups, students from George Washington Highschool, and Ald. Byron Sigcho-Lopez. A coalition of organizations including the Southeast Environmental Task Force, Chi-Nations Youth Council, United Neighbors of the 10th Ward, Southeast Youth Alliance, and many others held rallies throughout the turbulent multi-year permitting and review process.

2021-2022: EPA involvement, permit delays, lawsuits

In May of 2021, with construction underway on the Southside Recycling facility, Mayor Lori Lightfoot received a letter from U.S Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator Michael Regan. The letter noted “significant civil rights concerns” and called for pausing the operating permit review and a completion of a health assessment. Shortly after the letter was made public, Mayor Lightfoot announced that the permit decision would be delayed and community engagement would begin to draft a health impact assessment. Within days RMG filed a $100 million lawsuit against the city in federal court (and again in Cook County Circuit Court after a federal judge rejected the first case), arguing for compensation and the issuance of an operating permit.

On February 18, 2022, Mayor Lightfoot’s Office formally denied RMG’s operating permit for the Southside Recycling facility. The announcement followed three community engagement sessions held as part of an eight-month Health Impact Assessment that was “recommended and guided by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.”

RMG has released a statement vowing to fight the decision.

Outdated zoning fails to adapt to changing community needs and uses

As of today, Southside Recycling will not initiate metal scrapping operations at 11600 S. Burley Avenue on the banks of the Calumet River. However, the process that led to this point raises broader concerns about lack of proactive, consistent, and community based planning that is failing to unlock valuable riverfront land for more river-conscious, environmental justice focused, and neighborhood-supported uses.

Between the announcement that General Iron would be relocating, and the permit denial almost four years later, there were accusations and miscommunication, countless protests and rallies, a hunger strike, a letter from the US EPA, and millions of dollars in lawsuits. The timeline above is indicative of a flawed process — one that shifts the burden onto community residents and relies on Chicago’s outdated by-right zoning procedures. The lack of comprehensive zoning code updates that include considerations for equity, sustainability, and public health continues to fall short of balancing the needs of industrial land users and community residents.

The Long-term industrial planning in Chicago

The relocation of General Iron from an industrial corridor on the north side to an industrial corridor on the south side represents a missed opportunity to plan for the industrial corridors across the City in a systematic way that takes into account equity, the environment, and public health. In 2016, the Department of Planning and Development kicked off a process to review and modify existing land uses and zoning within individual industrial corridors, called the Industrial Corridor Modernization process. The department started with the North Branch Industrial Corridor, which at the time was home to General Iron, and has gone on to complete additional ones, including Kinzie and Ravenswood. The City is now beginning to take a broader approach by looking at multiple industrial corridors at the same time, particularly in the Far South, home to the Calumet Industrial Corridor — which could provide land use and zoning recommendations that are more comprehensive in a specific geographic region. Before this planning process officially begins, the City should consider holding off on permitting additional industrial facilities in industrial corridors. A community engaged planning process is an essential step to ensuring that the future of a corridor aligns with health, environmental, and economic development priorities and that proposed zoning changes reflect that alignment. Continuing to allow historic industrial uses that may no longer be suited to the area before the planning process has occurred locks in that practice over the long-term, and disallows flexibility within the planning process itself.

Inconsistent with our collective vision for Chicago’s rivers and riverfront communities

The Chicago River Design Guidelines outline how properties along the Chicago River should be developed and improved to create aesthetic cohesion, to enhance the natural environment, and to provide public access and recreational opportunities, all while balancing the needs of active industrial uses critical to the City’s economy. The guidelines apply to any new development on the former General Iron site, but do not extend to any facilities proposed for the Calumet River, including Southside Recycling’s proposed site Advancement of Chicago’s vision for healthy, thriving rivers, as documented in Our Great Rivers, requires having a set of design guidelines and frameworks for all the rivers in Chicago’s boundaries, including the Little Calumet and the Calumet River. Among these goals, the vision encourages river-adjacent land use that addresses environmental impacts to humans and the river ecosystem itself. Riverfront industrial users must protect the quality of the waterway and habitat it would sit along, as well as ensure that other uses of the waterways, like recreation, are not hindered by its operations. Along our rivers, we should be actively seeking activities and facilities that will not contribute to any additional pollution to our air and water, especially if uses are near residential areas. Existing zoning regulations still allow these types of uses adjacent to waterways. The case of Southside Recycling provides a collective opportunity to step back and think about the need for land use and zoning changes that better reflect how we want to utilize our rivers.

Missed opportunities and potential for change

The General Iron case highlights the need for proactive change to city policy and zoning codes. In addition, it underscores the need for the City to be prepared with community-vetted ideas for where new and moving industries can be sited, and to proactively track and plan for precious riverfront land.

As noted in previous blogs in the Yesterday’s Zoning series (MAT Asphalt and Cougle Foods), the Chicago Zoning Code not only allows, but promotes industrial uses next to rivers and residential areas. Unlike previous case studies, activists and residents were able to mobilize against unwanted development. But, robust community engagement for development review should not need the extremities of hunger strikes and federal lawsuits. Existing rules and frameworks governing land use, zoning, and permitting processes are in need of a review to balance economic needs with environmental and community priorities.

The decision to deny RMG’s occupancy permit shows that it is possible for the City to use health and environmental justice data and community input to reassess development decisions. This is a critical first step in evaluating cumulative impacts in overburdened communities.

The decision to deny RMG’s occupancy permit shows that it is possible for the City to use health and environmental justice data and community input to reassess development decisions. This is a critical first step in evaluating cumulative impacts in overburdened communities. Chicago, use this momentum toward improving permitting, land use, and zoning processes to center resident voices and create resilient, equitable, and healthy neighborhoods.

Stay tuned for the upcoming conclusion as MPC recaps the challenges of industrial land development in Chicago. We will review lessons that can be learned, how those lessons can be applied to the new citywide planning process, We Will Chicago, and demonstrate opportunities for equitable, responsive dialogue between developers, communities, and the City of Chicago to prosper.

Footnote: 1 (415 ILCS 5/39) (from Ch. 111 1/2, par. 1039) Sec. 39. Issuance of permits; procedures.

For more in depth background information on the General Iron/Southside Recycling saga and the larger fight over industrial development on the south side check out this article from Block Club Chicago by Maxwell Evans.