One of the key principles that civic leaders embraced was the creation of affordable and market-rate homes side-by-side the redeveloped public housing.

When civic leaders initially pledged to promote the success of the historic Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) Plan for Transformation, one of the key principles they embraced was the creation of affordable and market-rate homes side-by-side the redeveloped public housing.

This mixed-income strategy was promising because it integrated formerly segregated populations. With a shortage of quality affordable housing located in mixed-income neighborhoods, there was also enthusiasm about the actual creation of new homes in viable communities, at prices affordable to the local workforce such as nurses, teachers, and other moderate and low income households. Affordable homes are defined as rentals for families making up to 60 percent of the Chicago Area Median Income (AMI) — around $45,000 per year for a family of four— and homeownership opportunities for families making up to 120 percent of AMI — approximately $90,000 for a family of four.

These affordable homes are crucial for the new mixed-income communities, knitting together the lowest-income families living in public housing and upper-income ones choosing the market-rate opportunities. They also can compensate for part of the loss of public housing in the city.

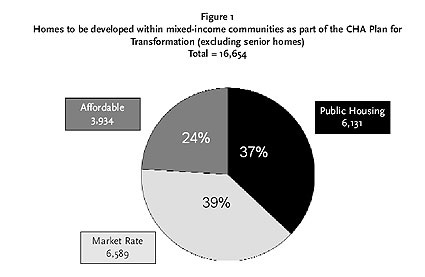

The Plan’s fundamental commitment is to provide, by the end of the Transformation, 25,000 new or rehabbed homes affordable to public housing residents — a number equivalent to the legally occupied CHA apartments as of Oct. 1, 1999. The Plan reserved about 9,000 of those homes for the elderly, and around 16,000 for families.1 Nevertheless, compared to the more than 29,000 CHA family apartments as of Oct. 1, 1999, the Plan represents a major loss of approximately 13,000 family apartments, most of them so rundown that they were left vacant.2 The Plan to situate more than 6,000 of the new family homes within mixed-income communities is indeed a promising strategy — spurring the creation of similar amounts of affordable and market-rate homes.

As the Plan moved toward implementation, with developers selected and financing strategies refined, the goals for the mixed-income communities also were revised to reflect that, by 2009 (see Fig. 1):

SOURCE: CHA FY2006 Moving to Work Annual Plan (2005)

- Approximately 6,100 homes would be created for public housing residents;

- Around 3,900 would be affordable to the local workforce, as defined above; and

- About 6,600 would be market-rate homes.

This Update looks at the status of affordable housing development within mixed-income communities created by the Plan, reflects on the diversity of the affordable homes available to date, and explores the challenges involved in achieving the Plan’s affordable housing goals. The report acknowledges the dramatically different realities of each mixed-income site in terms of market demand, size and history, and tries to identify common themes and overall trends that may affect each site.

PLANNING AND TRACKING AFFORDABLE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT WITHIN MIXED-INCOME COMMUNITIES

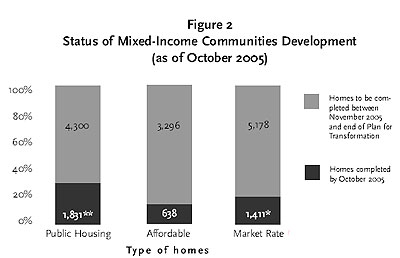

As of October 2005, approximately 3,900 homes have been built or rehabbed as part of mixed-income communities. This represents about a quarter of those projected to be completed by the end of the Plan. The majority (1,844) are public housing, with nearly half of them developed in or before 2000. Another 1,400 are market-rate (around 80% of them for sale in the Near North area). The number of completed3 affordable homes is 638. Fig. 2 summarizes the status of affordable housing in comparison to public housing and market rate homes.

Source: CHA Development Teams, CHA and Chicago Dept. of Housing (2005)

* Includes 1,120 for-sale homes located in the Near North area, off-site Cabrini-Green

** 972 of these completed in or before 2000

Of the 638 affordable homes developed since 2000, 565 are rentals and 73 are for sale. In a climate where rental housing is increasingly difficult to finance and create — especially for families with children — it is encouraging to see new family apartments becoming available at affordable prices.

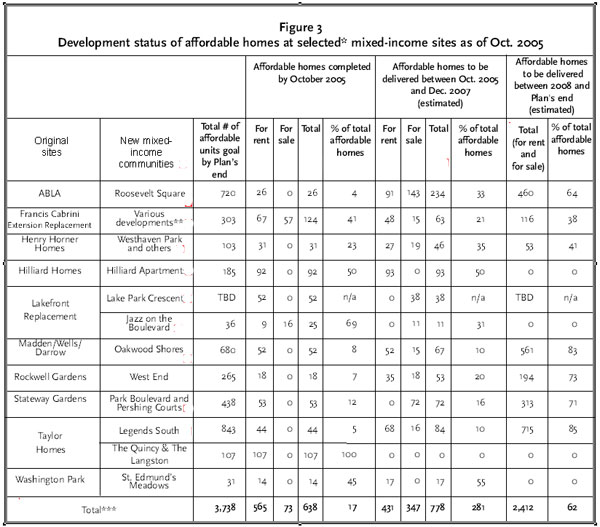

The data by redevelopment site (see Fig. 3) shows that, to date, except for the new communities in the Cabrini-Green area and Jazz on the Boulevard, no homes for sale fall into the "affordable" category at any of the major mixed-income development sites, most of which have achieved less than 25 percent of their overall affordable housing goals.

SOURCE: CHA Development Teams, Chicago Dept. of Housing and CHA (2005)

* Chart does not include mixed-income communities that have recently included in the CHA Plan for Transformation such as Keystone (Lakefront Replacement) and Fountainview (Lawndale). See CHA FY2006 Moving To Work Plan for more information at www.thecha.org.

** Including Domain Lofts, The Larrabee, Mohawk, North Town Village, Old Town Square, Old Town Village, Orchard Park, Renaissance North, and River Village

*** Excluding Lake Park Crescent

Usually, mixed-income, mixed-finance deals take longer than conventional housing development. The CHA estimates that the average mixed-income redevelopment timeline spreads over five years, from the initial meetings of the working group to the delivery of the first homes. Also, in Chicago’s typical mixed-income sites, rental phases are scheduled to be completed first, with homeownership phases coming online later. As such, it is no surprise that the production of affordable homes has not taken off yet.

Looking forward, a steady stream of affordable housing development (778 planned for the next two years at major mixed-income sites) is scheduled for all the sites. Of those, at least 347 will be for sale. The timely completion of these homes is critical, given that five years into the Plan, only a very small amount of affordable homes for sale has been completed.

While CHA tracks and reports on the status of public housing development and rehab as part of the Plan for Transformation in its Annual Plans and Reports, there has not been a similar tracking effort for the affordable, non-CHA homes. Estimated development timelines, breakdown of units for sale and for rent, income limits, and size of units are among the key aspects that need to be monitored to guarantee the creation of truly mixed-income communities.

CREATING HOUSING OPPORTUNITIES AFFORDABLE FOR A VARIETY OF FAMILIES

Entities like the Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT), which sat in the shadows of the old Stateway Gardens, lauded the CHA Plan not only because of its intent to replace a neglected public housing stock, but also because some of the new homes would be affordable to its own employees. "Quality affordable homes in quality neighborhoods are hard to come by in a prospering city like Chicago," explains IIT Vice President of External Affairs David Baker. "So, we launched an employer-assisted housing (EAH) program for Park Boulevard — the redeveloped Stateway Gardens — to invest in the Plan, our neighborhood, and housing solutions for our own workforce."

IIT, as part if its commitment to invest in the Plan, its neighborhood and its own employees, reached out to other employers in the neighborhood to similarly invest in those employees who opt to buy in Park Boulevard. De La Salle Institute, Illinois College of Optometry, and IIT are all three underwriting homebuyer education costs and down-payment assistance as part of a joint employer-assisted housing strategy coordinated with Park Boulevard. At the October 2004 kick-off meeting, 125 employees showed up at the trailer for the first public viewing of the new models, and 80 enrolled in homebuyer counseling per the EAH program. However, when the first new homes became available to purchase (though not to be ready for occupancy until 2006), only one of these employees accessed affordable homes, in great part because all the affordable homes available (17 out of 61 for-sale properties) were priced for families at the upper end of the income limit, i.e., earning around 120 percent AMI.

The case of Park Boulevard is not unique. At a number of sites, most of the first affordable homes available are being or will be occupied by either the upper-income tier (high-income families living in market-rate units and middle-income families around 120 percent of AMI) or the lower-end of the income spectrum (those living in affordable homes for rent priced for families 60 percent AMI or less). Looking forward, and thanks to the "Affordable Housing Commitments" amendment of Chicago’s Municipal Code (September 2003), opportunities may be more plentiful for production of homes for sale for families earning up to 100 percent AMI in future phases of mixed-income development,4 but neighborhood employees, employers and other stakeholders are still concerned about the outcomes.

A variety of affordable homes (i.e., a balanced mix of homes priced for families at different income levels, both for rent and for sale) guarantees a continuum of income levels and avoids the creation of economically polarized communities of low-income renters and upper-income homeowners. The promotion of a variety of income levels can help minimize the tensions and “divided camps” between homeowners and public housing families that have affected some early mixed-income communities across the nation. Research also shows that "mixed-income housing may be more difficult to manage when there is a dichotomy between the subsidized and market-rate renters, rather than a gradual climb represented by moderate income tiers."6

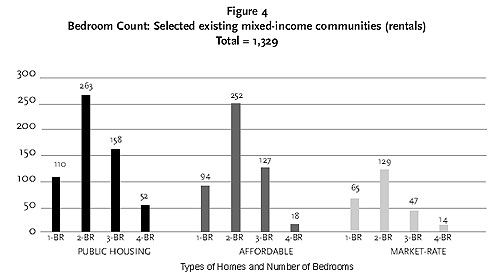

Regarding the size of affordable homes, an analysis of more than 1,300 rentals currently available at mixed-income sites (see Fig. 4) shows that the bulk of the new affordable homes for rent at selected sites are two- and three-bedroom apartments, with only 18 four-bedroom apartments completed.7 The Regional Rental Market Analysis managed by MPC in 1999, and more recently the Homes for a Changing Region report by Chicago Metropolis 2020, both underscore the need for sizable rental homes for large families looking for affordable housing. It is a hopeful sign to see a significant amount of three-bedroom homes for rent already available for low-income families. Looking ahead, it will be important to provide four-bedroom rental homes and guarantee that the affordable homes for sale provide options for large families.

Source: Dept. of Housing (1998-2005) and CHA Development Teams (2005)

FUNDING AFFORDABLE HOUSING DEVELOPMENT WITHIN MIXED-INCOME COMMUNITIES

The bulk of the funding to build affordable homes comes from low-interest loans, tax credit-leveraged equity, and grants and subsidies issued by public agencies, including the Illinois Housing Development Authority (IHDA) and the city’s departments of Housing (DOH) and Planning and Development (DPD). Some of the most widely used funding sources are Low-Income Housing Tax Credits, Community Development Block Grants (CDBG), HOME monies, Tax Increment Financing (TIF) funds, and tax-exempt bonds. The average mixed-income development must coordinate between five and ten different layers of financing.

The Plan has required a huge financial effort from the City and, a meaningful contribution from the State, in terms of funding commitments.8 Also, it is worth noting that the Plan has spurred innovative ways of using public and private funds. For instance, TIF funds have been used for the first time to finance single-family housing development.

Despite the variety of sources, it is becoming increasingly difficult to cover the development costs of affordable housing due, to a greater extent, to the increasingly higher costs of housing development on these sites. At the beginning of the Plan, the average total development cost for a newly constructed unit of housing was around $130,000. (CHA allocated $90,000 per unit, intending to leverage the balance from the city and other sources.9) Five years later, the estimated cost of the vast majority of new homes developed as part of mixed-income communities is well above $200,000 per unit, with some developments approaching and even surpassing $250,000 per unit. Rehabilitation costs at these sites range from $138,000 to $208,000 per unit.

A number of factors have been identified by developers and other experts to explain these cost increases, including:

- the high cost of labor in the city;

- the increasing prices of construction materials (the Plan promised no differences in quality between public, affordable and market-rate homes);

- the transaction, legal and administrative costs derived from multi-layered, mixed-financing proposals;

- regulatory imperatives such as Section 3, Minority Business Enterprises and Women Business Enterprises (MBE/WBE) programs, "green construction" requirements, and provisions related to mandatory community processes; and

- changing local building codes and redundancies in the public sector review processes.

A thorough analysis of construction costs and development budgets at mixed-income sites would help better explain (and potentially address) some of the causes behind these increasingly higher costs. A comparison with development costs at other sites (within and outside the city) also would shed light on this issue.

CONCLUSIONS

Eyes have appropriately been focused, through the Relocation Rights Contract, the CHA Independent Monitor reports and a number of Plan for Transformation-related studies, on the production of public housing committed to former CHA residents. But public and private partners must also pay special attention to construction timelines, number, type, size and income limits for these affordable homes in order to gauge progress against goals, and guarantee a steady production of homes in these new communities.

A sufficient commitment of resources will also be needed to guarantee the implementation of such a plan. Ever-increasing development costs raise concerns about how to fund affordable housing with limited public resources. A deeper analysis of costs may help identify ways to maximize the use of development dollars.

The affordable component within mixed-income communities plays a vital role in the overall strategy to transform Chicago’s old, dilapidated public housing high-rises into viable neighborhoods open to families of all economic backgrounds. Consistent with its initial pledge to promote the success of the Plan for Transformation, MPC recognizes that a diversity of housing options is essential if the new communities are to attract and sustain the families from diverse economic backgrounds as proposed. It’s all "easier said than done," so transparency and accountability in the planning and production process continue to be key to leveraging support and achieving the laudable goals of the Plan.

ENDNOTES

- The most recent version of the Plan reserves 9,446 homes for seniors and 16,554 for families. CHA: FY2006 Moving To Work Annual Plan, available at www.cha.org.

- 29,278 CHA family units existed as of October 1, 1999. Only 16,248 of them (56 percent) were occupied.

- "Completed" refers to units occupied or ready for occupancy (Certificate of Occupancy issued) as of October 2005.

- This amendment established that "whenever financial assistance is provided to any developer in connection to the development of 10 or more housing units, the developers shall be required to establish at least 20% of the housing units as affordable housing…" Affordable housing is defined as homes priced for families earning up to 60% AMI (for rental developments) or up to 100% AMI (for for-sale developments). Developers also can pay a fee in lieu of the development of these affordable units, or combine both.

- See, for example, the Baltimore case in "Linking Housing and Public Schools in the HOPE VI Public Housing revitalization Program: A Case Study Analysis of Four Developments in Four Cities" by J. Raffel, L. Denson, D. Varady and S. Sweeney (2003), available at www.udel.edu/ccrs/pdf/LinkingHousing.pdf.

- "See "Mixed-Income Housing: Factors for Success" by P. Brophy and R. Smith in Cityscape: Volume 3, Number 2 (1997) available at www.huduser.org/periodicals/cityscape/vol3num2/success.pdf.

- Of the 18 four-bedrooms found, 17 were located at one development, St. Edmund’s Meadows in Washington Park.

- For an analysis of city-based funding sources, see Chicago Rehab Network’s most recent report at www.chicagorehab.org

- See MPC Factsheet #1: "Transformation Plan Update October 2000" available at www.metroplanning.org.

MPC is deeply grateful to the following funders who made this report possible: The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, The Partnership for New Communities, Chase, Polk Bros. Foundation, Sara Lee Foundation, Washington Mutual and Bowman C. Lingle Trust.