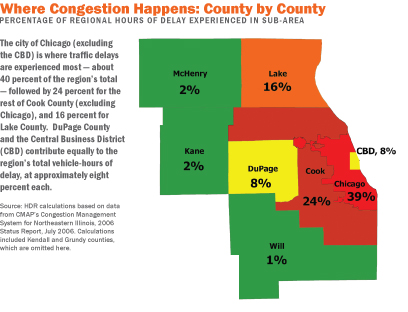

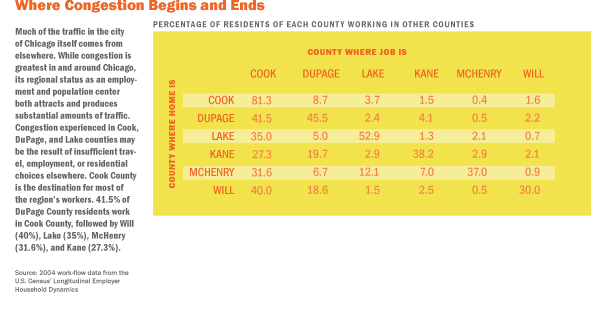

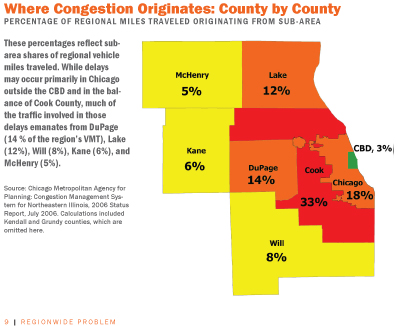

Over the entire regional roadway network, including expressways and arterials, congestion is most severe in Chicago itself, followed by the balance of Cook, then Lake and DuPage counties. Given that these are the region’s largest job and population centers, these results are not surprising. However, outside of Chicago, congestion on arterial routes is much greater than on expressways, and produces more air pollution and resulting environmental costs. Additionally, where gridlock happens and where traffic comes from are two different things. The graphics here demonstrate that while traffic jams may be most common and costly in Chicago itself, much of that traffic originates elsewhere in the region.

Not all congestion within the region is the same

Congestion in the Chicago metropolitan area is about as pervasive on arterial routes as it is on expressways. For the area as a whole, the proportion of vehicle-hours of travel that occur under congested conditions is 26.6 percent for arterials and 28.6 percent for expressways. There is a common conception that resolving congestion is largely a question of managing gridlock on expressways. However, in this case, a regionwide assessment is misleading because traffic patterns outside Chicago are very different than those within the city.

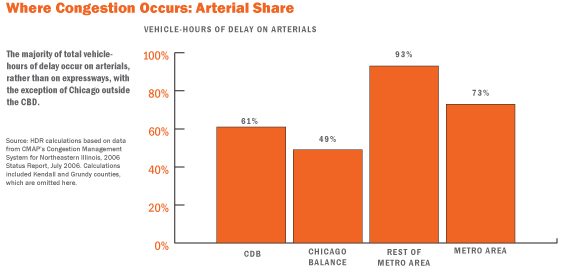

Only in the city of Chicago itself is congestion greater on the expressways than on arterial routes. In every other part of the region, the percentage of vehicle-miles and vehicle-hours traveled under periods of congestion are higher on arterials than on expressways. Likewise, the majority of total vehicle-hours of delay occur on arterials, rather than on expressways, with the exception of Chicago outside the CBD.

Understanding the numbers

CMAP’s 2006 Congestion Management System (CMS) report measured recurrent congestion that results from the interaction of limited road capacity and usual traffic volumes throughout the day. Using this as a starting point, the researchers conservatively estimated delay relative to average speeds under relatively uncongested conditions (as opposed to free flow).

For each sub-area of the region, and separately for arterials versus expressways, the average speed is calculated for the uncongested section as the ratio of total vehicle-miles of travel to total vehicle-hours of travel. This was used to determine hours-per-mile and vehicle-hours of delay.

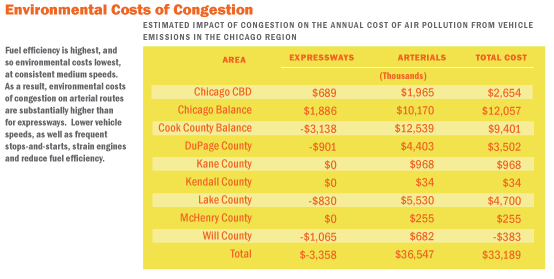

Environmental Costs of Congestion

Environmental costs are difficult to measure. Calculating the cost of wasted time and wasted fuel is a simple affair compared with the complex assessment of the environmental costs of congestion. The value of time and fuel can be determined much more readily than the value of environmental quality. Among the adverse effects associated with motor vehicle air pollution are respiratory disease, “structural deterioration, crop damage, and decreased visibility” (Federal Highway Administration, 2000). Automobile emissions include greenhouse gases such as carbon dioxide and methane, and other pollutants like carbon monoxide, nitrous oxides, and particulate matter. These gases contribute to global climate change, which could have immense and unimaginable costs, only some of which can still be avoided. While these costs are very real, they are difficult to quantify.

Ultimately, the environmental cost in dollars is contingent upon society’s values of environmental integrity. The City of Chicago has developed a global reputation for being an environmentally minded pioneer, drafting its own Climate Action Plan, promoting and enabling increased bicycling, and rewarding new architecture and building retrofits designed to conserve energy. The Chicago region is beginning to follow suit, as evidenced by the Metropolitan Mayors Caucus’ Greenest Region Compact. Because the Chicago area appears to value environmental integrity highly, the calculations here for environmental costs will be low estimates.

With the preceding caveat, it is possible to begin to assess the environmental cost of congestion. Overall, the environmental cost of congestion is estimated at approximately $33 million a year. Automobiles produce pollution whenever operating, but emit noxious fumes at a higher rate when traffic slows and driving patterns include increased cycles of acceleration and braking. This explains why, in every area of the region, the cost associated with arterial congestion is higher, and in some cases vastly higher, than for expressways. In some cases, the impact of congestion on expressways is actually negative. This is because automobiles operate most efficiently at medium speeds. Congestion on expressways can slow traffic to the point that emissions are actually lower than they would be in a relatively uncongested situation, thus forgoing emissions that would otherwise have resulted.

Understanding the numbers

Determining the environmental costs of congestion required a three-step process: determine the cost of one ton of relevant pollutants, determine the output of pollutants resulting from congestion, and, from that, determine the total cost of pollution. This report used air pollution cost estimates from the Federal Highway Administration’s Highway Economic Requirement System — State Version. For example, one ton of carbon monoxide has damage costs of $100, one ton of sulfur dioxide has damage costs of $8,400.

Policy Implications

Congestion occurs throughout the region, with the greatest amount of delay occurring in and adjacent to Chicago , and a significant portion originating in other counties. Although congestion on major expressways is a significant challenge for Cook County and Chicago , it is actually arterial routes — such as LaGrange Road , Roosevelt Road , or Green Bay Road — that are more of a challenge in outlying counties.

Strategies to reduce regional congestion must:

-Be regional in scope in order to address the point of origin and point of

destination, as well as the network of roads in between.

-Not simply address the expressway system at the expense of arterial routes. In

many places, arterial routes are already the main source of concern, and

diverting more traffic to them will exacerbate existing conditions.

Due to the greater fuel efficiency associated with expressway travel, it is actually arterial routes that contribute more substantially to the air pollution caused by congestion. As the region pursues strategies to both mitigate its congestion and improve its environment, particularly air quality, it will need to be vigilant about not unintentionally increasing arterial traffic. Congestion mitigation strategies that focus solely on increasing expressway speeds, perhaps by increasing expressway prices, could inadvertently divert traffic to arterials. Instead, a coordinated strategy to increase travelers’ transportation options, while reducing traffic levels and increasing speeds on both expressways and arterials, will be necessary to reduce congestion without inadvertently adding to regional air pollution.

Return to the main page of Moving at the Speed of Congestion.