The Chicago River has been in the public eye in the past few weeks, a spotlight it too rarely enjoys. First, the Obama Adminstration came down on the side of disinfection; Chicago Mayor Richard M. Daley subsequently reiterated his ongoing support enhanced treatment and a cleaner river. Asian carp concerns, which will likely escalate further with Wednesday's discovery of a Bighead carp in Lake Calumet (which is between the O'Brien Lock and Lake Michigan, meaning this fish had total freedom to enter the lake), have been all over the news as well. That's why MPC took the opportunity at our recent Annual Luncheon to have Illinois’ U.S. Senate candidates Alexi Giannoulias (D), Mark Kirk (R), and LeAlan Jones (Green) weigh in on the future of the river. Due to time constraints at our luncheon, and space constraints in most media coverage, neither the question posed to the candidates — "Do you support re-reversal of the Chicago River?" — nor their answers, were placed in the context the issue deserves.

A more thorough question would have been, "Given northeastern Illinois' water supply constraints, transportation and recreation goals, the ongoing threat of interbasin invasive species movement, and downstream water quality and ecosystem impacts, should we be weighing the costs and benefits of hydrological separation of the Great Lakes and Mississippi River basins, or even re-reversal of the Chicago River itself?" That doesn't roll off the tongue, but it merits asking and answering.

On May 24, 2010, 13 US Senators, including Dick Durbin (D-Ill.) and Roland Burris (D-Ill.), issued a joint statement calling for an expedited study of hydrological separation by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. The Ill. Dept. of Natural Resources, and represenattives from such nonprofit organizations as the Alliance for the Great Lakes, Friends of the Chicago River, Great Lakes St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, and Natural Resources Defense Council, all have made comparable statements in support of investigating the feasibility of separation or re-reversal. In short, serious people are talking seriously about the future of the Chicago River, and for good reason.

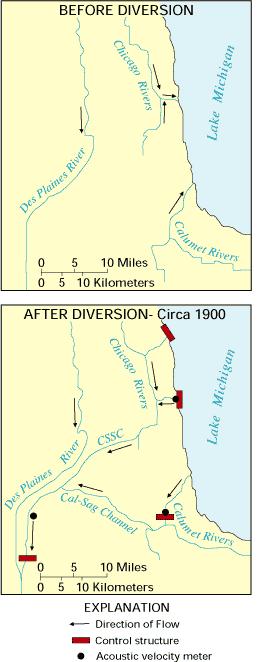

The basic history of the reversal is well known. Before the advent of modern waste water treatment and stormwater management technologies, the majority of Chicago's sewage was being dumped into the Chicago  River, which flowed to Lake Michigan. A common quip at the time was the "solution to pollution is dilution." However, then as now, Lake Michigan was the region's primary water source.

River, which flowed to Lake Michigan. A common quip at the time was the "solution to pollution is dilution." However, then as now, Lake Michigan was the region's primary water source.

Chicago's growth as a national power center was severely hindered by constraints on the availability of clean water, as well as thousands of deaths from cholera, typhoid and other waterborne diseases. The reversal of the Chicago River, in combination with Chicago's role as the hub of a burgeoning national rail network, unleashed the city and region's potential, and we haven't looked back.

The construction of the Chicago Ship and Sanitary Canal (and later the Cal-Sag Channel) linked the Great Lakes and Mississippi River, allowing for the interbasin transfer of barge traffic and other commercial activity. Those shipping lanes remain active to this day; sizable volumes of bulk goods like road salt, sand, and scrap metals make their way throughout the Chicago Area Waterway System (CAWS).

Simply put, in 1900, reversal had two basic goals: to provide clean drinking water for Chicago by moving wastewater away from Lake Michigan; and to establish Chicago as a hub of interbasin freight movement.

With the great exception of the basic operation of CAWS, a lot has changed since 1900. There seems to growing consensus that the following five goals should drive decision-making going forward. It remains to be seen whether hydrological separation or other fundamental changes to CAWS is the only route to achieving these goals.

***

1. Improve the water quality and ecosystems of Lake Michigan, Chicago area rivers, and the Mississippi Basin, through better treatment and reduced stormwater and combined sewer overflow effects.

Waste water treatment technologies and stormwater management practices have improved greatly since 1900, allowing for the feasible return of water to the lake. After all, everyone else on the Great Lakes, from Duluth, Minn., all the way to Toronto, Ont., does exactly that. They pump water, use it, clean it, and return it. Effluent disinfection to remove harmful pathogens from the river is only the first and most immediate step toward ever returning treated waste water back to the lake. Subsequent measures would be needed to remove things such as ammonia, phosphates, and a range of pharmaceuticals that are currently not addressed by our treatment facilities, or anyone else's for that matter. That's why northeastern Illinois is responsible for about 5 percent of the pollutant load in the Gulf of Mexico's dead zone.

Additionally, it simply isn't true that our region doesn't put dirty water back into Lake Michigan. The capacity constraints of our region's combined sewers mean that in large storm events we're sometimes forced to release a combination of stormwater and untreated sewage directly back into the lake. The largest event in recent history, an immense storm in September 2008, resulted in more than 11 billion gallons of untreated sludge getting dumped in the lake. This argues for more measures to prevent stormwater from entering our region's sewers, and that's where green infrastructure solutions from rain barrels to Eco-Boulevards could play a role.

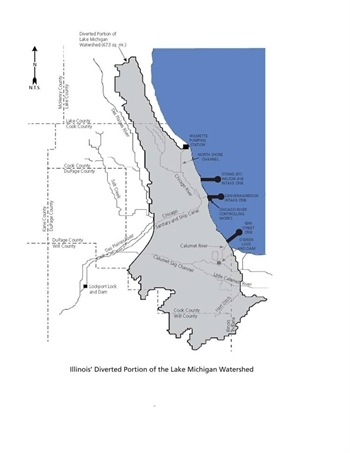

Another important concern with stormwater runoff is that it actually counts as water we've removed from Lake Michigan.  When we reversed the river, we fundamentally altered the hydrology of the region. Before the reversal, all the rain falling in the gray area of the map seen here would have run off into one of our rivers, and ultimately to the lake. Now, the vast majority runs into our sewers, gets treated along with our legitimate sewage, and then is sent downstream. The U.S. Supreme Court considers that stormwater a portion of our diversion, and thus it's part of our potential water supply. In any given year it's between 25 and 30 percent of our actual diversion, and is usually in the vicinity of 500 million gallons a day.

When we reversed the river, we fundamentally altered the hydrology of the region. Before the reversal, all the rain falling in the gray area of the map seen here would have run off into one of our rivers, and ultimately to the lake. Now, the vast majority runs into our sewers, gets treated along with our legitimate sewage, and then is sent downstream. The U.S. Supreme Court considers that stormwater a portion of our diversion, and thus it's part of our potential water supply. In any given year it's between 25 and 30 percent of our actual diversion, and is usually in the vicinity of 500 million gallons a day.

2. Provide clean drinking water for the growing Chicago region, easing reliance on strained aquifers and rivers.

Because of our proximity to Lake Michigan, the region as a whole doesn't face immediate water shortages, but pockets of the region do. One outcome of the recently completed Northeastern Illinois Regional Water Supply/Demand Plan is a growing understanding that the deep bedrock aquifers and shallow aquifers used by many suburban communities are under unsustainable stress. Many of those communities will likely need Lake Michigan water to complement or supplement their existing supplies, and several towns in Lake County are already pursuing that option.

However, because of the river reversal and subsequent diversion rules, we can only take so much —3,200 cubic feet per second. As of 2005, we were at about 88 percent of that. While that means we have some ability to take additional water out of Lake Michigan, additional towns and population growth will move us toward our cap very rapidly. Our economic competitors on the Great Lakes — including Cleveland, Milwaukee, and Toronto — don't have the same constraints, because they send their clean, treated effluent to the lakes, then pump out more. Not tomorrow, and not next year, but within the next century, the fact that our ability to use Lake Michigan water is capped will hurt us.

3. Enhance the capacity and efficiency of Chicago’s intermodal freight facilities.

Moving freight on water is extremely energy efficient. Barges can carry the load of 80 tractor trailers, using far less oil, and emitting far fewer fumes. In a region that loses $7.3 billion a year because of traffic congestion, we need all the alternatives we can get. Most of the goods that come to or leave the Chicago region by barge are bulk "piles" like road salt and coal, rather than separable containers that are often seen double-stacked on trains. Those bulk goods are off-loaded and, over time, trucks come to pick up and remove the material. Until oil costs, emissions-based fees, or other factors make it more cost-effective to move containers by barge than by truck, there may be little opportunity to increase the amount of barge-to-rail traffic. That day is coming, but there are currently few sites where freight can be moved efficiently from rail to barge.

No one contemplating hydrological separation or re-reversal of the river is, or should be, considering an end to water-borne freight movement through the region. Inadvertently putting more trucks on the road is simply a bad idea. Instead, any separation scheme should be coordinated with investments that prepare the region for greater interaction between barges and trains.

4. Sustain growth in recreational and tourism uses of the CAWS.

In 1900, or even in 1971 (the year before the Clean Water Act was passed), the idea of paddling a kayak, sculling, or fishing in the Chicago River would have struck most people as lunacy. However, since 1972, with the consistent achievements of the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District, the quality of the water has increased tremendously. Boat tours and water taxis ply the river, sailboats and motor boats make their way to and from marinas, and there are even a few folks who live on the river. As is the case with freight movement, any separation scenario must account for continued growth in these uses.

5. Eliminate risk of interbasin species transfer.

Asian carp dominate the news, but they're only the most recent of dozens upon dozens of species that have used CAWS to move from the Great Lakes to the Mississippi River or vice versa.

The map here shows the spread of zebra mussels; similar maps exist for round gobies, alewives, sea lampreys, and many others. Each of these species, regardless of the severity of their effects on their new environment, inevitably result in millions and millions of taxpayer dollars being spent on species-specific solutions. As an example, the electric barrier being used to slow the advance of the Asian carp (and the second one under construction) won't do a thing for invasive weeds or bacteria that could traverse the CAWS. So, as long as water flows between the basins, there is the risk of species transfer. Unless something is done to eliminate that risk, we'll just keep fighting one species after another.

***

We are capable of improving water quality in Lake Michigan, Chicago area rivers, and the Mississippi River Basin. We can increase the region’s available water supply for people, businesses and ecosystems. There are steps we can take to strengthen our position as a freight hub, and we know how to make tourism and recreation easier, safer and more enjoyable. We also know that we have to stop interbasin species transfer, partially so we can stop wasting money on halfway solutions, but primarily so we can protect the lakes and rivers that we value.

Does any single one of these 21st Century goals merit separation or re-reversal? Perhaps not. Do all five, taken together as one vision for the future of our region, justify that kind of investment? Maybe so. That's what we don't know and need to find out.

This is not an Asian carp issue, a disinfection concern, nor a debate of tour boats vs. locks. This is a question about what we want the Chicago region to be in 100 years.

A century ago, they asked themselves the same question, and selected reversal because it was the most efficient of three options to meet the goals of the time. We now face another turning point in the history of the Chicago region, and must be as prudent and patient as our forebears were. Hydrological separation and re-reversal are daunting -- perhaps even intimidating -- but they are not crazy. They may well be the best choice we can make to secure the future we want.