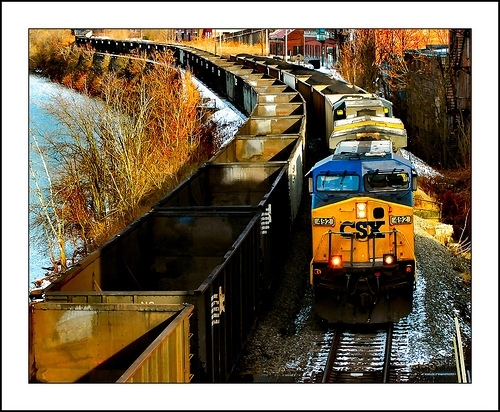

The Green TIME Zone strategy is a great example of coordinate, public-private investment in community redevelopment, building on shared regional assets, including criss-crossing freight lines.

For nearly 100 years, through the 1980s, Chicago’s south suburbs were rich with opportunity. Steel mills and rail yards powered metropolitan Chicago’s economy, putting the local workforce in high demand. As the nation transitioned to a service-based economy – decades before the current Great Recession – signs of economic struggle were everywhere in the Southland: pockmarked commercial strips, abandoned factories-turned-brownfields, whole neighborhoods decimated by foreclosures.

Times were bad – but today, the Southland’s future looks brighter.

The south suburbs are focusing redevelopment efforts around transit stations to help people save time and money on their commutes.

Photo by Josh Hawkins

How did things turn around? Dozens of communities put aside differences, came together around shared assets like criss-crossing freight lines, and got to work on an economic revitalization strategy with support from local, state and national public and private sector partners. Today, the Green TIME Zone strategy is attracting green manufacturing companies to locate near intermodal freight facilities as well as developing and rehabbing energy-efficient homes near transit. Some 13,000 new jobs – many of them green – will generate $2.3 billion in new income to the area over the next 10 years.

The story of the south suburbs was how Bruce Katz, founding director of the Brookings Institution’s Metropolitan Policy Program, chose to open his keynote speech before an international audience gathered in Chicago last week. Their economic turnaround – based on a unique regional business plan, created through collaboration between the public and private sector, and with an eye toward a new way of doing business – brings to life many of the concepts debated by national and international thought leaders at “Global Metro Summit 2010: Delivering the Next Economy,” co-hosted by Brookings, the London School of Economics, the Alfred Herrhausen Society, and Time magazine.

Case studies from the U.S., Italy, Germany, Spain, and South Korea, among others, contributed ideas, advice and words of caution about how to get to the innovation-fueled, export-driven, low-carbon “next economy” that Katz forecasts.

Katz the pragmatist acknowledged, “Washington is fundamentally broken, and most states are broke.”

But Katz the visionary, as well as other panelists, left no room for excuses from either business or government. Coordinated action by both sectors, the summit conferees concluded, is needed to drive a “cut and invest” approach to regional economic growth.

Cut and invest may seem a contradiction, but coming from Illinois, which faces a $13 billion budget deficit, it makes a world of sense to me. We cannot only cut our way to growth. As we cut, we also must stretch public resources through smarter spending and strong partnerships with the private sector.

Tom Wilson, CEO of Allstate, a Fortune 100 company based in Chicagoland, echoed that sentiment at a pre-summit gathering. The common goal of business and government, he said, “should be for America to remain the largest and most productive economy in the world,” with both sectors sharing in responsibility and risk.

When the economy went south, American businesses cut inventories and employment to stay afloat; as a result, American companies have a cash balance of around $1 trillion – yes, trillion. An uncertain economy and unfriendly government were reasons cited by the business community for not investing in the past, but that has become an excuse for not acting, Wilson suggested.

Indeed: American companies must start investing again in their growth to lift our communities. But they cannot do it all. The federal government must be a partner, investing simultaneously in education, research and development institutions, as well as economic and physical infrastructure, to encourage businesses to make some of the long-term investments needed to shape the next economy.

It’s a heavy lift, to be sure – but two hands are better than one. At the summit, Chicago Mayor Richard Daley promoted the example of Chicago Career Tech, an innovative program that provides unemployed middle-income workers with free skills retraining to help them make the shift to high-demand technology-based careers. This initiative is successful precisely because businesses and nonprofits are partners, identifying the most in-demand skills to drive learning and providing on-the-job training opportunities. That’s money and time well spent, for all parties.

Models such as Chicago Career Tech and the Green TIME Zone strategy can and should be replicated in other metropolitan regions, and metropolitan Chicago can learn from other cities, as well. Places across the country – Northeast Ohio, Greater Seattle, the Twin Cities – have developed sector-specific, data-based business plans to guide their economic growth. They are acting with discipline to implement these plans, and in so doing attracting new employers, homeowners, and investors – all of whom thrive on predictability, even in the most stable economic times.

Imagine if all metropolitan regions, which already account for 83 percent of U.S. population and 90 percent of U.S. GDP, developed and then stuck to a more focused, asset-based plan for their own economic growth? The next economy demands exactly that.

This article was written for Citiwire.net.