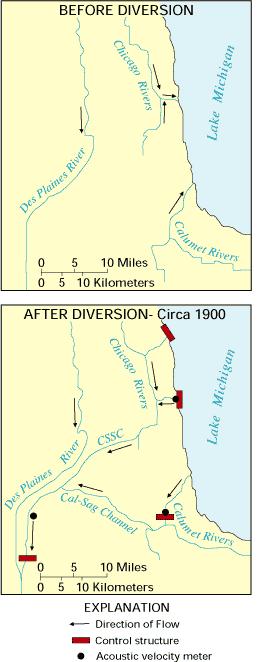

Last Wednesday, on a pretty standard cold and windy February day in Chicago, I attended the second advisory committee meeting for Envisioning a Chicago Waterway System for the 21st Century, a cooperative effort of the Great Lakes Commission and the Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative to investigate the costs and benefits of separating the Great Lakes from the Mississippi River (see some reflections on the first meeting here).

In addition to receiving some high praise about our short film, A Fork in the River, I was very pleased with the presentation by the consultant team selected for the study. The presentation focused primarily on the study process, but there was also a substantial portion (see slides 14-22) dedicated to the potential for growth in both rail and barge commodity movement due to expansion of the Panama Canal, slated for completion in 2014. It remains to be seen whether there are scenarios for hydrological separation that could actually increase the amount of intermodal freight movement on the Chicago Area Waterway System (CAWS), but for many people in the room, it was the first time they heard an objective transportation and logistics expert suggest there might be. More than anything else, opportunities within CAWS were assessed through a global lens, forcing a fair bit of rethinking for some.

And then the weather warmed up. All that snow from Groundhog Day started to melt, and a lot of it had nowhere to go because it was piled up on streets and alleys. Starting this past Sunday there were combined sewer overflows into CAWS on three consecutive days — snow and ice, after all, are just frozen stormwater. So all that road salt, along with a substantial dose of sewage, antifreeze from leaky cars, motor oil, and who knows what else, is now making its way through downtown Chicago, down the Des Plaines and Illinois Rivers, and eventually to the Mississippi. Of course there are better ways — more green infrastructure would slow runoff and naturally filter some of the water, and there are alternatives to traditional road salt, including sand. Either way, sewer overflows and water quality concerns flip that global lens right around and force us to assess changes to CAWS back at the local, regional, and watershed levels.

The fact is, there are different geographies of concern when it comes to hydrological separation, and with those come different perceptions of risk, opportunity, cost, and benefit. Success is defined differently based on the scale at which you are concerned with the issue. If we only think of stakeholders in terms of their occupation or industry — environmental group or industrial user, fishermen or barge operator, etc. — then we miss these geographic stakes, which I think actually unite varied interest groups within a specific geography.

When it comes to CAWS and this discussion of hydrological separation, I see five distinct geographies, and specific concerns and goals within them. I would hope that as the Great Lakes Commission, Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, and the consultant team weigh the pros and cons of various options, these geographic lenses will be taken into account.

Downtown Chicago. The Chicago River has the potential to be the heart of downtown, rather than the edge,

Downtown Chicago. The Chicago River has the potential to be the heart of downtown, rather than the edge,

much as it is envisioned in the Central Area Action Plan and the Chicago Riverwalk concept. Realizing that vision will be a challenge so long as the water (which is primarily wastewater effluent from upstream treatment plants) is carries the stigma (or reality) of being dirty. While water quality has improved over the last 40 years, there's still room for improvement. Improved water quality and reduced incidence of sewer overflows into the Chicago River could increase property values, encourage architects to orient places and spaces toward the water, boost river tourism, and spur social activity beyond seasonal strolling and dining. - The service area of MWRD/Illinois' diverted portion of the Lake Michigan watershed. The next scale up is one where water resources management is the primary concern. CAWS is the region's plumbing system, and for the foreseeable future it's how we dispose of our wastewater and stormwater (it's possible that at some point in the future we would return treated wastewater or stormwater to Lake Michigan, much like everybody outside Illinois does). Any option that leads to increased risk of flooding isn't really an option at all, but conceivably separation could occur in conjunction with a number of things we should be doing right now to improve water management anyway — investments in green infrastructure, maintenance of modernization of gray infrastructure, water reuse, etc.

- CAWS. Our waterway system actually stretches into Indiana, and connects man-made canals with rivers, rails and roads. Barges and tugs transporting large amounts of high volume, low value goods (think road salt and sand), as well as recreational boats, ply the waters all year long. In theory, as oil becomes more expensive, and as transport times get shorter with investment in rail plans like CREATE and the aforementioned expansion of the Panama Canal, opportunities will grow for waterborne movement of goods and intermodal exchanges. The current system isn't perfect, but we certainly don't want to lose what we have. Congestion on our highways is bad enough. It's possible that with some ingenuity and investment there would be a scenario for hydrological separation that actually improves the cost-effectiveness of movement of goods through CAWS. This will be the biggest challenge of the process.

- The Great Lakes community. Folks from Buffalo to Duluth are, I think it's safe to say, less concerned with the development of downtown Chicago or wastewater management in northeastern Illinois (so long as that wastewater stays out of Lake Michigan), than they are with keeping invasive species out of the Great Lakes. There's the material concern of protecting current commercial fishing efforts, as well as a sincere desire to do no further harm to the ecosystem. Concern with CAWS doesn't stop there. All that road salt and sand on the barges comes from and goes somewhere, and so continued or increased movement of goods is certainly a concern. Additionally, the continued diversion of water out of the Great Lakes is a problem for some. More and more people are waking up to the fact that the availability of low cost water is going to be an economic driver for the Great Lakes region in the century to come, so the more we can use, clean, and put back into the lake, then use again, the better.

- The Mississippi River community. Two things seem to have been forgotten in all of this discussion about Asian carp. First, all that water we divert out of Lake Michigan goes somewhere else, and second, species can move in multiple directions. Not many folks in the Gulf of Mexico appreciate our contribution, modest as it may be, to their worsening dead zone, nor are they fans of zebra mussels. They do like shipping goods up the river and into the lakes however.

The costs and benefits of specific options need to be viewed through these different lenses. The purpose of the hydrological separation study is to evaluate options for ending invasive species movement though CAWS, but the complementary goals are improving transportation, stormwater management, and water quality. The relative value of stormwater management, for instance, greatly varies depending on your geography, as does the definition of "improve."

Eliminating occasional discharges of wastewater and stormwater into Lake Michigan (a concern at the Great Lakes scale), for instance, isn't necessarily the same as reducing basement backups in the suburbs of Chicago (a concern throughout the MWRD service area), nor is it the same as reducing phosphorous, nitrogen and nutrients loads downstream (a Mississippi River concern). Can they all be achieved simultaneously? Yes, in theory. But a crude wall blocking water flow back in to the lake would match someone's idea of improvement, while severely missing the target for others.

There will be dozens of situations like that as different options are considered. It's a fascinating and immensely complex enterprise, and it's certainly a bigger issue than some rambunctious fish. That's why it's great that the Great Lakes Commission, Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative, and their consultant team are wading into these murky waters and trying to provide some useful ideas to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for their eventual assessment of the issue. I don't know whether there really is a possible scenario for hydrological separation that would satisfy the array of stakeholders out there, and I don't think anyone else truly does at the moment either. What I do know is that unless you consider how success will be defined at different geographies of concern, you'll never have a solution that truly matches the challenge — and opportunities — at hand.