Source: U.S. Census and Illinois DNR, map by Ryan Griffin-Stegink

This map is also available as a high-resolution PDF.

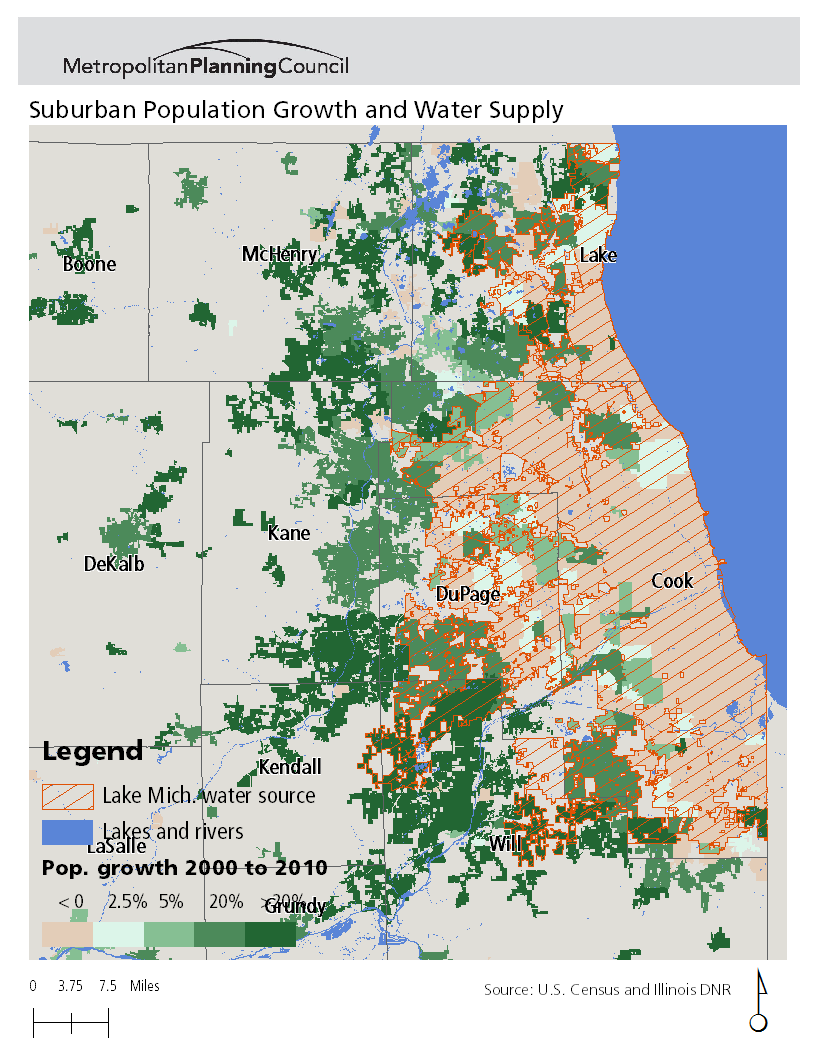

2010 Census data reveals dramatic shifts in the region's population over the last decade. While most coverage of the 2010 Census data has focused on the political ramifications of these population changes, this new portrait of our region means a host of policy implications as well, from the need for workforce housing to impacts on traffic congestion. Over the next several weeks, MPC will offer snapshots of some of these regional shifts and analysis of how they will affect our work. Today's post assesses the relationship between population growth and water supplies.

MPC Research Assistant Ryan Griffin-Stegink contributed to this post.

Census snapshot

Recently released 2010 Census data confirms what many suspected: The collar counties of the Chicago region are growing more quickly than its core. While Cook County—encompassing Chicago and inner suburbs such as Cicero and Wilmette—shrunk by 3.4 percent, the surrounding counties experienced rapid growth. Kendall County grew the fastest, more than doubling in population since 2000. Over the same time, Will, Grundy, Boone and Kane counties grew by more than 25 percent, while McHenry and DeKalb each added at least 15 percent. While these shifts do reflect movement from city to suburbs, they also mean a shift from Lake Michigan water to other sources, primarily groundwater.

As Chicagolandh2o.org's water source map indicates, most residents living in Chicagoland's inner core get their water from Lake Michigan. Lake Michigan water is abundant, but not infinite, and unlike other states, Illinois does not return its used water back to the lake. Given large volumes of water, and long pumping distances, sustainable use of Lake Michigan is primarily a matter of efficient infrastructure management. As demand grows with increasing population, Lake Michigan water often becomes a more attractive proposition. Many DuPage County communities switched in the 1990's, and just last year several communities in western Lake County were granted an allocation of Lake Michigan water by the Ill. Dept. of Natural Resources.

In contrast, many communities in outlying, faster-growing areas pump groundwater and/or river water. Underground aquifers, in particular, are more limited in the amount of water that can be pumped from them. Deep aquifers recharge very, very slowly, as rain seeps back into the earth, and shallow aquifers are susceptible to seasonal droughts. According to the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning's “Water 2050: Northeastern Illinois Water Supply/Demand Plan” and the Ill. State Water Survey, deep aquifers in particular cannot be expected to meet all future demand scenarios. One of the variables in used in those demand scenarios (see page 29 of Water 2050) was the location of future population growth. Generally speaking, population growth focused in Cook and DuPage counties would lead to lower rates of growth in water demand, while growth in Kane, Kendall and McHenry counties would lead to higher rates. The 2010 Census data suggest we may be facing the latter. Larger lot sizes and more lawn watering are largely responsible for higher per capita use rates in the outlying, less urbanized, counties.

The table below shows the 20 Chicagoland municipalities that grew the most from 2000 to 2010. Those highlighted in green rely on groundwater or river water.

| Municipality | Pop. Added | Growth Rate |

| Aurora |

54909 |

38.40% |

| Joliet |

41212 |

38.80% |

| Plainfield |

26543 |

203.58% |

| Huntley |

18561 |

323.93% |

| Romeoville |

18527 |

87.59% |

| Bolingbrook |

17045 |

30.26% |

| Oswego |

17029 |

127.79% |

| Elgin |

13701 |

14.50% |

| Naperville |

13495 |

10.51% |

| Montgomery |

12967 |

237.01% |

| Round Lake |

12447 |

213.06% |

| Yorkville |

10732 |

173.40% |

| Lockport |

9648 |

63.51% |

| Tinley Park |

8302 |

17.15% |

| Shorewood |

7929 |

103.16% |

| Crest Hill |

7508 |

56.33% |

| Frankfort |

7391 |

71.13% |

| Carpentersville |

7105 |

23.23% |

| Minooka |

6953 |

175.09% |

| Algonquin |

6770 |

29.09% |

Planning and policy responses

Fortunately, municipal and county officials in these communities also are tackling the challenge at the subregional level. Communities in DeKalb, Kane, Kendall, Lake and McHenry counties, as well as the counties themselves, have come together to form the Northwest Water Planning Alliance (NWPA). The NWPA is increasing awareness of water issues, developing shared policies that complement or support Water 2050, establishing consistent water use reporting standards, and improving data and modeling tools to support more timely and informed decision making by its members. It is a laudable effort, and MPC is pleased to be a consulting member of the Technical Advisory Committee. There are plans in place for a similar group comprising Grundy, Kankakee and Will counties. The benefit of the NWPA is that elected county and municipal leaders are taking charge of their water futures, sharing success stories, and developing management strategies at the scale of the problem. Aquifers and rivers pay no heed to jurisdictional borders, and thus solutions must do the same.

Sustainable management of the region's aquifers and river water is needed, particularly as population grows, but that hardly means Lake Michigan communities are off the hook. One important measure Water 2050 recommends is improved stormwater management. An immense amount of water is lost as stormwater runoff, and because of our diversion of water away from Lake Michigan, it counts as water taken from the lake. We do not use for it anything, but we could and should. In 2005 (a drought year), Illinois lost an average of approximately 500 million gallons of our potential water supply every day, which is about twice as much groundwater consumed daily in the entire region. Capturing that water for reuse, using green infrastructure to keep it out of the sewer, or even treating some portion of our sewage and returning it to the lake, would reduce that loss and make more Lake Michigan water available for pumpage. A bill currently in the Illinois Senate would lay the foundation for this infrastructure by setting minimum standards for rainwater collection and reuse systems. Property owners can help by planting their lawns with native vegetation, which require less irrigation and can recharge underground aquifers with filtered rain as much as 25 times faster than traditional lawns.

Managing our region's water supplies sustainably has always been a challenge; population shifts revealed in the 2010 Census only heighten that challenge. Water 2050 and the NWPA both demonstrate the need to collaborate across borders, and reflect a growing consensus that while Illinois' water supplies are relatively abundant, the time is now to make sure they stay that way.