Having gotten a bad weather forecast from the guy at my local bike shop, I spent a fair amount of time this past Sunday—however long it takes to ride a bike 40 miles during high winds, driving rain, and a foot of standing water in the street in a few places in Evanston—thinking about Cook County's sewers, effluent, and rivers. I tried to wait out the rain over lunch at a place in Winnetka, and though it just kept raining, I overheard a conversation that really summed up the hydro-situation I was watching out the window. A self-admittedly overweight guy was explaining to his friend that he was holding off on dieting until he could kick his habit of biting his nails, and his friend was trying to convince him how counter-productive and illogical that was, as the two problems, while related, were fundamentally separate but each necessary for the guy's quality of life. Trust me, it's a good metaphor for Cook County's current stormwater and wastewater issues, just bear with me.

The fact is, a lot of that rain I rode through drained to combined sewers, where it mixed with raw sewage, and then, because there was simply so much of it, was discharged without treatment to a local waterway. Because I was north of Chicago, I knew that combined sewer overflow (CSO) would then flow downstream, through the heart of the city, on its way to the Illinois River. As of writing this on May 31, there have been CSOs on seven consecutive days. I also suspected that given the intensity and duration of the rain there was a good chance that some of that CSO water would need to be re-reversed back into Lake Michigan to prevent flooding, and unfortunately, I was correct.

Some day, when the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District's (MWRD) massive Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP, also known as the Deep Tunnel) is totally complete, reservoirs and all, the frequency of CSOs in and around Chicago should diminish greatly. The purpose of TARP is to capture and store this untreated mix of stormwater and sewage until the rain stops and there is sufficient capacity at one of MWRD's plants to treat all that water, after which it gets released into the waterways and flows downstream. The tunnels are already finished, and that alone has helped matters, but the reservoirs, which hold a lot more water, won't be completed for several more years.

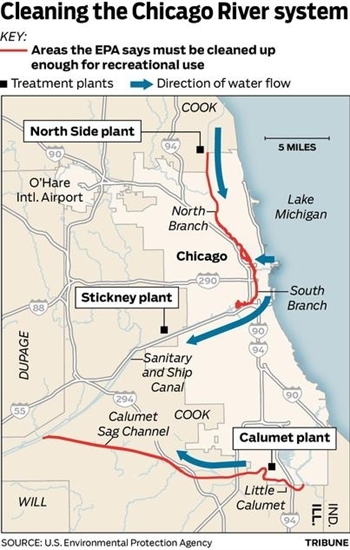

None of that is news. What is news is that on May 11, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (USEPA) issued a letter to the Ill. Environmental Protection Agency (IEPA), telling them and the Ill. Pollution Control Board (IPCB) to improve the water quality standards for the portions of the Chicago Area Waterway System that are used most heavily for recreation (see map).

The majority of the water in those sections is treated effluent released from MWRD's North Side and Calumet wastewater treatment plants. Improved water quality standards requires additional treatment, and in this case it's a process called disinfection, during which chlorine or ultraviolet radiation are used to kill bacteria in the water, thus making it safer for people who come in contact with it. USEPA estimates that the cost of installing the needed technology for disinfection is somewhere between $26 and $72 million. MWRD's estimates are higher. The question is whether the costs are worth the benefits, and IPCB may decide that within the week.

Exactly what are those benefits? Well, cleaner water seems to me to be a benefit in its own right, and certainly the reduced risk of illness or disease is a plus for the tens of thousands of boaters, paddlers, and fishers who come into contact with the water. Perhaps that reduced risk will spur even more use of the waterways, which is great for marinas, kayak tours, and river cruises. Those are benefits that just happen once the disinfection switch gets flipped.

The greater economic impacts will require a more concerted effort to orient new development along the waterways toward them at the same. That could mean recreational waterfront access at the Lathrop Homes site, extending the Chicago Riverwalk as Union Station is rebuilt, integrating the Calumet into plans for transit-oriented development in Blue Island, and so on. Cleaner water, and as importantly the perception of cleaner water, could boost riverfont property values and increase marketability, but the onus is on us to take advantage of those effects through conscious design and planning. That's the only way we get the biggest possible bang for our disinfection buck.

However... as we saw this past weekend, sometimes we get a whole lot of rain and CSOs as a result. When that mix of stormwater and sewage is discharged into our waterways, it won't matter a whole lot how much disinfection technology we have installed. The water is still going to be contaminated and a risk to public health, at least until the rain stops and the water flows downstream (at which point it becomes someone else's problem, which isn't really a solution). For some, that somehow provides a justification for not investing in disinfection technology—"So long as we have CSOs, disinfection doesn't matter."—but that's a false and misleading argument, just like the overweight nailbiter's. You can quit biting your nails and go on a diet at the same time, just as we should be investing in disinfection and accelerating CSO solutions simultaneously. They are separate issues, requiring distinct sets of resources.

But accelerating CSO solutions won't be easy. The MWRD's massive Tunnel and Reservoir Plan (TARP, or the Deep Tunnel) was designed to drastically reduce the frequency and severity of CSOs in the Chicago area. A system of tunnels (which are completed and already functional) and reservoirs (the smallest is finished, the larger two are still being dug) will capture and store CSO waters until the weather clears and there is capacity at one of MWRD's plants to handle all that water. If TARP performs as intended, we could be talking CSOs in the single digits per year, as opposed to the dozens and dozens we experience now. Unfortunately, there are several reasons to doubt that TARP will perform as intended unless additional action is taken, and these themselves are distinct issues from the substantial challenge of finishing the reservoirs.

Some of those challenges are internal. For example, CSO flow from northern parts of Chicago and some suburbs will travel by tunnel to the McCook reservoir, a distance of 30 plus miles to the west and southwest. Unfortunately, storms tend to come from the west in this region, meaning that rain will deposited downstream first, and the system will begin to fill with that water... where will the water from upstream go? If there is no available capacity in the system, then it will overflow, and so it's possible that we'd still see CSOs along the North Branch of the Chicago River, even when TARP is finished. The University of Illinois is currently doing a study for MWRD on how to optimize flows and capacity to address that possibility, and it remains to be seen whether the actual operational parameters of TARP will match what was intended.

There are external challenges as well. TARP was never intended to be the region's stormwater system, but rather our last line of defense against flooding, which is different. The fact of the matter is that when rain falls throughout Cook County, it falls on public and private property, where some of it (not enough, that's where green infrastructure should come in) soaks into the ground, while the rest flows into locally managed sewers. These systems eventually feed into MWRD's larger collection sewers, and in the event of a large storm, into TARP. For TARP to function as intended, those local feeder systems need to function too. That's the domain of municipal governments, not MWRD, and there's some inconsistency throughout the region as to the condition and management of those local systems. If street drains are clogged, or pipes don't have sufficient capacity, then it's possible water will never to get to TARP (or not as quickly as it should), and there will be local overflows. If the feeder systems don't convey water to MWRD's portion of the system appropriately, then they could exacerbate CSO issues.

Then there are the reservoirs themselves. They're simply not done yet, and are not slated to be totally finished until 2029. Why? More or less, they are dug at the speed at which the material extracted from them can be sold for use in construction projects, which means it's a variable speed. A stagnant construction market means the pace has slowed. It's done that way to avoid the need to move all the rock material to storage somewhere, then move it again later, which should lower costs. There are really only a couple of solutions for this—either find a way to use all the rock (we're talking a small mountain's worth) or dig it out and pile it up, then deal with it later. The former is slow and conditional on finding buyers. The latter would be initially quicker (though it would still take some time), but creates a long-term problem of what to do with the big pile afterwards. It also increases costs.

So the question with the reservoirs is one the region isn't really asking itself—are we willing to pay more (both in dollars and in carbon emissions for an extra round of moving lots of rock) in order to accelerate completion of TARP and its resulting reduction of CSOs? And, how does the possibility that TARP may not perform as intended because of other internal and external factors affect our region's answer to that question?

Disinfection is a right thing to do to improve our region's waterways, but it's not the only one. We need to finish TARP and do everything in our power to make sure it works as intended—fix local feeder systems, reduce inflows through appropriate use of green infrastructure, optimize conveyance within the tunnels, and finish the reservoirs. It remains to be seen how much the region is willing to pay and how quickly we're willing to act, but to truly protect our waterways, improve water quality, protect property, and meet federal requirements, we're going to need to do them all.