Emily Cikanek

By David Schumacher

By David Schumacher - January 22, 2013

Experiencing Drought is a series of guest profiles by public works officials on the impacts of drought on northeastern Illinois communities. This is the first in the series, view other posts from the Experiencing Drought series. For more information, please contact Abby Crisostomo at acrisostomo@metroplanning.org.

Municipality: Aurora, Ill.

Water Source: Fox River and deep groundwater aquifers

Issue: Water quality of Fox River versus cost of pumping from deep wells

Outcome: Shift to well water, while implementing an impactful water conservation ordinance

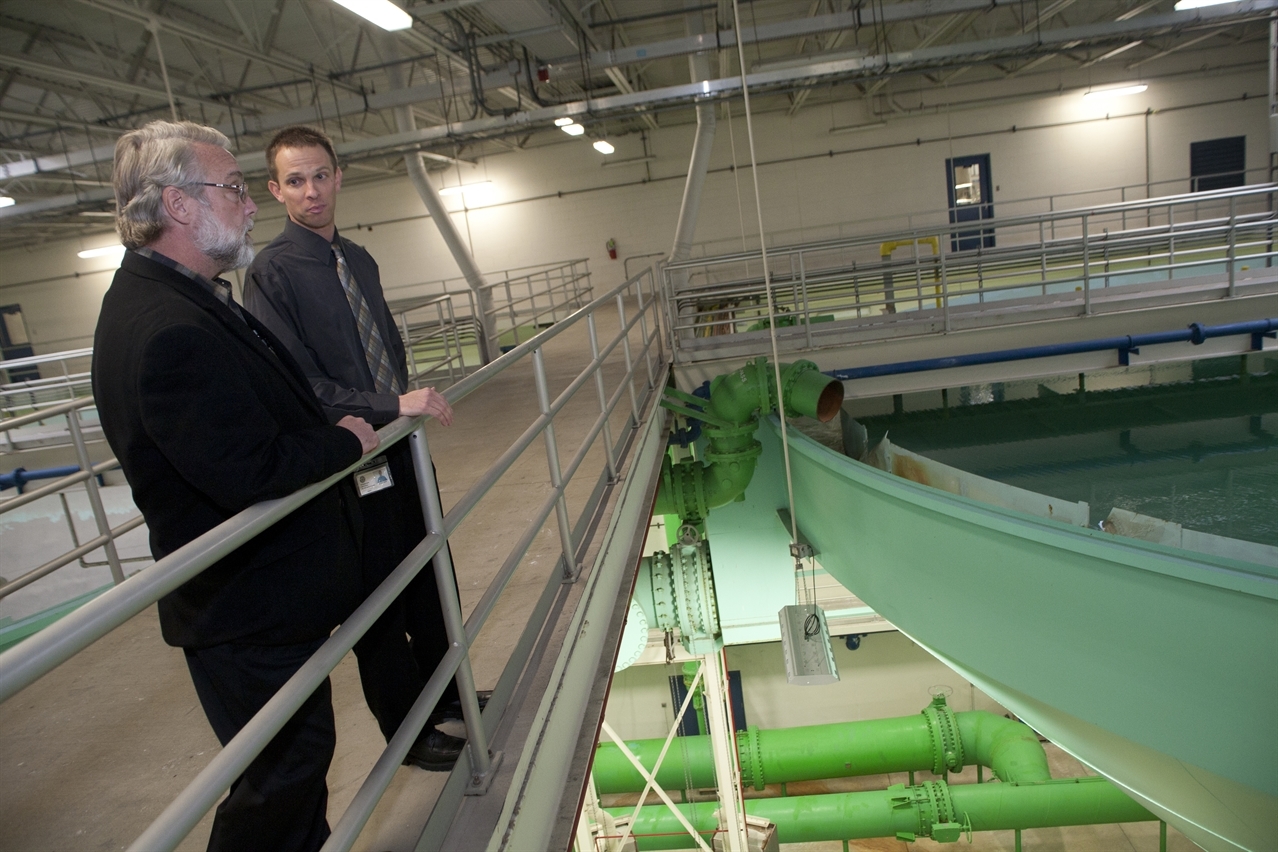

The City of Aurora is located approximately 38 miles west of Chicago, and is the second largest city in Illinois with a population of approximately 198,000. The city’s drinking water needs are met by a single Water Treatment Plant (WTP) which was constructed in 1992 and expanded in 2002.

The weather that we all experienced across the entire Chicago region from June thru September 2012 was hot and dry with brief periods of relief. The lack of rain over an extended period of time greatly affected the water demand from residents in our community which, of course, greatly affected the amount of potable water which had to be produced by the WTP.

The WTP can produce a rated capacity of 42 million gallons of water per day (MGD), and utilizes the lime softening process. The city uses three different raw water sources: shallow aquifer well water, deep aquifer well water, and surface water pumped from the Fox River. These are all blended together to receive full surface water level treatment—a somewhat unusual practice which, ironically, proved very beneficial during this year’s drought.

The city’s population and the average and maximum daily amount of water pumped from the WTP to citizens over the last 11 full years are shown in Table 1. The red highlighted numbers are all historical maximums.

Table 2 shows how the 2012 drought affected the total amount of water pumped from the WTP this year compared to historical maximums of past droughts. It is easy to see the challenges posed to the City of Aurora by the drought of 2012.

Because one of the city’s raw water sources is the Fox River, and the river’s water quality and quantity is directly affected by the amount of precipitation that falls into the river’s watershed, challenges can develop for the WTP. While the quantity or amount of water within the reaches of the river near the WTP was enough for Aurora’s needs, the reduced flows caused by the drought contributed to degraded water quality. For example, the total organic carbon (TOC) which is naturally occurring organic matter found in nature, was elevated this summer compared to other summers. Since the elevated levels of TOC must be removed by the water treatment processes, increased treatment was required to meet drinking water standards.

Large amounts of algae can cause filters, which remove particles in the water, to become clogged and back-up prematurely. If the clogging happens too quickly and in too many filters, the WTP can become overwhelmed and a serious situation can develop. As WTP staff noticed the levels of algae and TOC spiking in the Fox River, the raw water inflow was shifted to contain a higher percentage of well water (from both deep and shallow sources) to avoid problems due to high TOC and algae in the raw river water.

However, shifting the WTP’s utilization of raw water sources did have its consequences. More electricity is required to pump water from wells as compared to pumping raw water from the Fox River. Thus, the city attempts to maximize the use of raw river water at all times to reduce dependence on deep aquifers and to minimize electrical expenses. Due to the degraded water quality of the river during the drought, this was certainly not possible. The amount of electricity consumed, and the associated financial consequences, can be seen in the comparative numbers listed in Table 3.

Similarly, the amount of chemicals required to treat the water during the drought were significantly higher due to the larger gross amount of water produced, and the degraded quality of the raw Fox River water. Comparative values for chemical costs are also shown below in Table 3.

Aurora’s Water Conservation Ordinance (WCO) has proven to be a major tool in managing raw water resources, treatment costs, and future capital infrastructure expenditures. The ordinance was enacted in 2006 and permits lawn watering on an even-odd cycle based on a resident’s home addresses. The goal of the ordinance is twofold: education of residents in conservation practices and reduction of peak demands on the water production and distribution systems which occur typically during summer months when large amounts of lawn watering take place.

While many communities have similar conservation codes, the effectiveness of these ordinances is difficult to ascertain due to many variables at play including weather. In 2005, before the WCO was enacted, Aurora experienced a similar drought to the one in 2012 when the WCO was in effect. Table 4 illustrates comparisons between these events. High flow days, defined in Aurora as flows in excess of 25 MGD, were reduced by 50 percent and the absolute maximum daily flow was reduced by 5 percent. It should also be noted that the city’s population increased by 18 percent between 2005 and 2012.

Another way to judge the effectiveness of the WCO is to compare per person or per capita water usage to eliminate the population growth from the analysis.

Chart 1 indicates 19 years of average and maximum daily water usage per capita in Aurora. The blue line shows average per capita usage prior to the 2006 enactment of the WCO while the green line shows average usage after the WCO. These lines have a very similar slope and there is no offset between the lines which would indicate any sort of change occurred. This is to be expected as a WCO is designed to reduce peak or maximum demands.

The yellow line shows maximum per capita usage prior to the WCO while the red line shows maximum usage after the ordinance became effective. A 20 gallon per day decrease (offset) between the yellow and red lines is evident. Also, a decrease in the spacing between the green (average) and red (maximum) lines is apparent. Both observations indicate that the WCO is having a positive effect on reducing the maximum/peak usage levels on the city’s water supply systems.

Aurora will continue to monitor these trends into the future to further maximize the benefits of the WCO to protect our raw water sources and reduce long-term costs to citizens.

David has 10 years of experience in engineering consulting work designing and constructing wastewater treatment plant improvements and over six years of drinking water treatment utility engineering and management experience. He received a MS and BS in Civil/Environmental Engineering from the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. David is currently the Superintendent of Water Production for the City of Aurora, Ill.