vonderauvisuals via Flickr

Throughout January, MPC’s blog, The Connector, is running a series on the tangible benefits of Placemaking. Read the other entries:

Sometimes it’s hard to define what makes a great place, but you know it when you experience it. Great places lure people in with activities, people watching, shopping or just the experience of being around others and feeling a sense of connection. Does this only happen at organic farmers markets or outdoor cafes? Hardly. Placemaking doesn’t just occur in affluent communities or vacation hotspots. Chicago’s 26th street in Little Village, 18th Street in Pilsen, or the Glenwood Market in Rogers Park are evidence that the power of a vibrant public place transcends geographic and demographic boundaries.

Peter Kageyama, author of For the Love of Cities, writes that creating places worth caring about makes for strong communities. We couldn’t agree more. That’s why we have designed a blog series that considers the importance of placemaking for communities through a variety of lenses. The series will explore the economic, environmental, physical and social aspects that produce quantifiable benefits for a community and its residents.

Today’s post started out being about the health benefits of great places. And it still is, but I found that, rather than trumpeting how much less likely you will be to have diabetes if you bike to work every day, I had a lot more to say about how hard it is to actually achieve those benefits in this country. And, on a hopeful note, how a few small groups of people are making inroads against the odds.

A lot of ink has been spilled on the abysmal state of Americans’ health, much of it due to a sedentary lifestyle. As noted in a 2010 Brookings report, one of the biggest drivers of rising health care costs is the expansion of chronic diseases like obesity, diabetes, and heart disease—conditions exacerbated by people who are car-dependent. All would be substantially reduced if more walking were built into Americans’ daily routine. In “America’s Health Threat: Poor Urban Design,” a former leader at the Centers for Disease Control notes that the major health threat of the 21st century is how we build our cities. A grimly titled Atlantic Cities article,“America is a Walking Disaster,” opines that “in much of America, walking – that most basic and human method of movement, and the one most important to our health – is all but impossible.”

This makes me think of a comment a friend from Milan made to me after spending several months in Chicago. It seems like people here, she observed, fall into two categories: either they are very fit and go to the gym all the time, or they are very sedentary and overweight. In Italy, she observed, it seems like the majority of people are in between those two poles. Most people don’t purposely exercise much, but most aren’t overweight either. We just walk, she concluded. A lot.

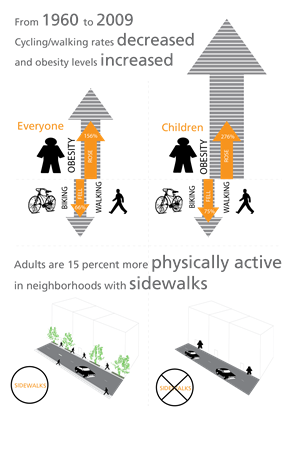

Click for larger image.

How much better off would we be if walking had not been engineered out of our lives? The British Columbia School of Planning recently found that the average male living in a compact community weighs 10 pounds less than his counterpart in a low density subdivision. While I’m usually skeptical of harkening back to the golden days of anything, statistics from a 2012 Benchmarking Report do point to some undeniable trends:

- Cycling and walking levels fell 66 percent between 1960 and 2009, while obesity levels increased by 156 percent.

- The percent of children who walk or bike to school fell 75 percent between 1960 and 2009, while childhood obesity rose 276 percent during that same period.

What else happened from 1960 to 2009? Spatially, we spread way out as a country, and in choosing more personal space, we chose to be further from one another. This is not a bad thing in and of itself – certainly, the end of racial covenants and the advent of more people having choices about where and how they lived was long overdue – but one of the results was a dramatic decline in the ability to walk anywhere in a reasonable amount of time.

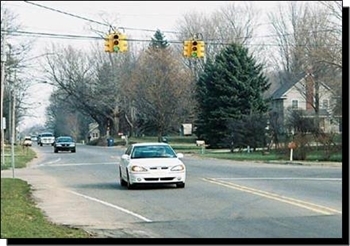

my sidewalk-less route to school

This isn’t just about personal decisions, because our options often are determined by others. Planners and city leaders in particular have a lot to do with how people live their lives. Growing up in my hometown of Kalamazoo, Mich., I lived about a quarter-mile from my high school. Rather than walk to school, however, my sisters and I begged our dad to drop us off. My parents – who grew up in then-dense Detroit and walked everywhere – were mystified. The reason was simple: there was no sidewalk on the route to school, and being seen walking in the ditch next to the road would have been totally uncool. What a missed opportunity to establish a very different culture among young people. So, sidewalks: pretty basic. A report from Active Living Research notes that the percentage of adults who are sufficiently physical activity is 15 percent higher in neighborhoods with sidewalks than in those without.

Not everyone faces such a stark lifestyle choice as “suburban sprawl versus compact urban living.” Much of the literature on this topic assumes that compact and urban equals walkable which equals healthy. The truth is that walkable communities are generally significantly more expensive than those with less density (and thus not an option for many), and people who live in low-income communities have many fewer options for walking and recreation. National data show that African-American and Latino adolescents are more likely to live in high-crime areas than are White teens, and that neighborhoods with more serious crime generally had residents who were less active overall. [1] Further, a 2011 Active Living Research study on park access found that 81 percent of mostly Latino neighborhoods in three states lacked parks, compared with 38 percent of mostly white neighborhoods. This pattern certainly plays out in Chicago: The densely populated Latino neighborhood of South Lawndale/Little Village has the least green space per capita of any neighborhood in the city.

In another Active Living Research study, “Do All Children Have Places to Be Active?,” researchers affirm that while adults who live in walkable neighborhoods (high density, mixed use, well-connected streets) tend to be more physically active than those who don’t, the relationship is less strong for lower-income and racial/ethnic minority populations. Why? Researchers note that while their neighborhoods may typically be dense, they tend to lack specific features that support walking (clean and well-maintained sidewalks, trees, street amenities), undermining the favorable effects of compact neighborhood design.

A few more statistics from this report: Lower-income groups and minorities have more limited access to well-maintained or safe parks and recreational facilities, which can partially explain the low leisure-time physical activity levels and high rate of obesity among racial or ethnic minority and lower-income children.

- A two-year assessment of more than 200 communities across the nation indicates that those with higher poverty rates and those that were predominantly African-American were significantly less likely to have parks and green spaces. [2]

- A national study of more than 20,000 adolescents finds that youth living in census-block groups with seven recreational facilities were 32% less likely to be overweight and 26% more likely to be highly active than were those who lived in one with no recreational facilities; the same study shows significant racial, ethnic and economic disparities in the distribution of recreational facilities, associated with disparities in physical activity and obesity. [3]

The truth is that crime and perceptions about safety do play as big a role as the built environment in how residents use their neighborhoods. In recent conversations with residents of the mid-South Side about their transit usage, for instance, MPC learned that many don’t use the otherwise convenient Green Line because they don’t feel comfortable walking home from the station after dark. This leads to more driving and less walking – and is a major lost opportunity: A 2011 Active Living Research study found that walking to and from public transit satisfies the daily physical activity recommendation for 29 percent of transit users.

So, many urban neighborhoods are lacking sufficient parks and recreational facilities, have inherent factors that discourage walking, and have residents who don’t feel safe, leading to worse health outcomes for its residents. What to do? In next week’s installment, I’ll take a look at two Chicago neighborhood groups that are fighting back in the face of these barriers to create healthier communities.

[1] Gordon-Larsen P, McMurray RG , Popkin BM. “Determinants of Adolescent Physical Activity and Inactivity Patterns.” Pediatrics, 105:e83, 2000.

[2] Powell L, Slater S, Chaloupka F. “The Relationship between Community Physical Activity Settings and Race, Ethnicity and Socioeconomic Status.” Evidence-Based Preventive Medicine, 1(2): 135–144, 2004.

[3] Gordon-Larsen P Nelson MC, Page P, Popkin BM. “Inequality in the Built Environment Underlies Key Health Disparities in Physical Activity and Obesity.” Pediatrics, 117(2): 417–424, 2006.