Photo courtesy of Abigail Grieve

The sand and water mixture at the bottom of this hole on a Lake Michigan beach helps us visualize groundwater in an aquifer.

MPC Research Assistant Shannon Madden authored this post.

If I asked you to describe an aquifer, or an underground deposit of water, you might have a harder time than if I’d asked about a lake or river. Aquifers seem mysterious, and we have trouble visualizing them. But since 19 percent of northeast Illinois residents (and 44 percent of the U.S. population overall) rely on groundwater and because climate change is expected to affect weather patterns and water supplies, our future depends on understanding and sustainably managing this valuable resource.

This week – National Ground Water Association’s (NGWA’s) National Groundwater Awareness Week – is a great time to start learning about groundwater and how we can develop better long-term water supply plans in Illinois.

When rainwater soaks into the soil, it fills spaces between rocks, sand and gravel. This is known as groundwater, and the geologic formations that contain groundwater deposits are aquifers. Unlike lakes, in which sediments and rocks settle beneath the water column, groundwater slowly flows through billions of tiny cracks and pore spaces between sand and gravel. (Aquifers are not like underground streams and lakes – a common misconception, according to the Illinois State Water Survey.)

To picture an aquifer, think about digging a hole in the sand along Lake Michigan. When you dig down to a level that’s even with the lake, you’ll find that the sand is saturated with water. That’s essentially what an aquifer looks like. The sand, gravel, and rock particles help filter the water, removing some of the contaminants that affect surface waters. (On the other hand, pollution from road salt, septic systems, industrial and agricultural chemicals, fracking, and natural occurrences of radium can cause other water quality problems in aquifers.)

The natural process of filling, or recharging, an aquifer, is often very slow. This is because aquifers are usually confined between layers of impervious rock, and water must trickle through crevices before reaching an aquifer. Shallow aquifers recharge before deep aquifers, simply because they are closer to the surface, but that also means they are often sensitive to drought conditions. Some deep aquifers take so long to recharge that we consider them non-renewable in our lifetimes. The point here is that groundwater resources are not unlimited; they are limited to the rate at which they recharge (and the costs we are willing to pay to pump water).

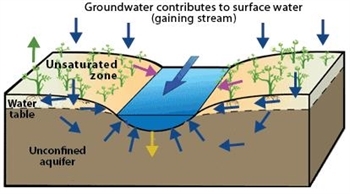

In addition to providing water for drinking, agriculture and industry, the NGWA reports that aquifers also contribute about 30 percent of streamflow. It’s pretty intuitive when you think about it – water flows downhill, so if the water table, or saturated level of groundwater, is higher than a stream or lake level, the groundwater will seep into the surface water. This is known as base flow, or the flow of a river without precipitation. The U.S. Geological Survey reports that about 80 percent of Lake Michigan’s inflow comes from groundwater. Clearly, this is an important resource in our region.

In this illustration, precipitation percolates into an aquifer, which then contributes to the stream’s baseflow. The opposite can also be true: If a body of surface water is higher than the water table, the surface water loses water to a nearby aquifer.

Photo courtesy of United States Geological Survey

Groundwater Resources in Illinois

Illinois uses three main types of aquifers:

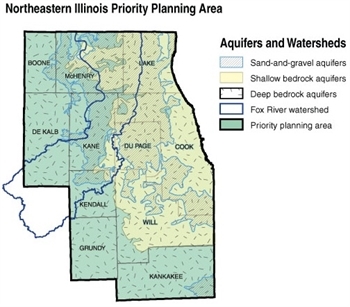

- Closest to the surface, about 25 percent of the state has shallow sand and gravel aquifers.

- Next are shallow bedrock aquifers in the northern third of the state.

- Finally, more than 500 feet below the ground, are deep bedrock aquifers used in northern Illinois.

You’ll notice on the maps in the links above that the aquifers cross many regions and counties, and they even extend to neighboring states. This crossover means that aquifer withdrawals in one location affect the water supply elsewhere, too. Aquifers are often layered at different depths, which you can see in the close-up of Northeast Illinois’ aquifers below.

Modified from Illinois State Water Survey map

While we can’t directly measure recharge rates, experts estimate them to determine the safe yield, or maximum amount of water, we can draw from an aquifer without damaging it as a long-term resource. The Illinois State Water Survey (ISWS) estimates that Illinois aquifers have a total safe yield of about 7 billion gallons per day. Excessive pumping causes drawdown (i.e. low water levels in a well, which increases the cost of pumping water to the surface), reduces streamflow, and can diminish surface water quality by concentrating nutrients and pollutants in smaller amounts of water – three good reasons why we should keep our withdrawals under the safe yield.

Tune in for tomorrow’s post on the research and analysis we need to protect this vital natural asset.