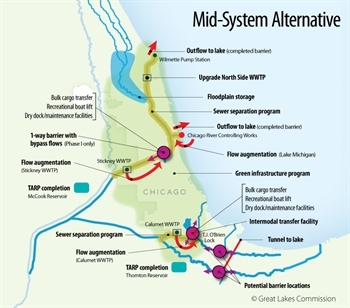

This is the latest in the Separation Anxiety series, detailing Josh Ellis' reactions and reflections as an advisory committee member for the Great Lakes Commission and Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative's Restoring the Natural Divide: Separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River Basins in the Chicago Area Waterway System. See the first, second, third, and fourth installments to get caught up to speed.

To this point in our ongoing discussions of the hypothetical implications of physically separating the Great Lakes and Mississippi River water systems at one or more locations in the Chicago Area Waterway System the most consistently and fervently voiced concern is that a physical separation would fundamentally damage waterborne transportation. Most boats don't jump very well, and certainly barges do not, so this is concern is understandable when people are openly talking about building physical barriers to water (and boat) movement in order to reduce the risk of invasive species movement between the two ecosystems.

With that said, to this point there has been little in the way of readily-available information about the movement of vessels—and probably more importantly, the goods on those vessel—through the system. That started to change at our most recent advisory committee meeting, held April 4th. I say "started" very intentionally, because while there were many transportation questions asked and answered at that meeting, there were many more left to be resolved.

Great Lakes Commission and Great Lakes and St. Lawrence Cities Initiative

We started to get some data on the flow of goods at the meeting, which was a relief, because to date we've been dealing with mostly anecdotes and rhetoric. According to information presented at the meeting by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, all told, about 20 million tons of cargo move through the Cal-Sag portion of the Chicago Area Waterway System every year. That includes cargo on deep water vessels that can operate in the Great Lakes and as far inland as Lake Calumet, but not past the O'Brien Lock just south of Lake Calumet. A barrier close to the lock would not affect those vessels. The same tonnage also includes cargo on shallow water vessels that carry goods on the expansive river network of the Mississippi River watershed. Those vessels can move through the O'Brien Lock, and so a physical separation there would have significant effects. The question is how much of the 20 million tons moves through that point, as opposed to to travelling elsewhere in the system, and the answer from the Corps was about 1.5 - 1.8 million tons annually. So that's what would be most immediately impacted by a separation—it's not a small number, but it's also not a large number, and it provides some clarity on what we're dealing with. About twice as much tonnage moves on shallow vs. deep. Tonnage on shallow draft boats has dropped about 50% since 1994, while tonnage on deep drafts has increased significantly in the same timespan.

This is all useful information moving forward. Slowing down the movement of waterborne freight affects costs, and costs determine whether a shipper opts for barge, rail, or truck. If the trans-loading required to move some low value, high volume good over a physical separation in the waterway slows its movement down by 5%, for instance, someone may opt to ship their coal, chemicals, or road salt by some other means. Of course, other things affect modal decisions as well—the price of fuel, infrastructure condition, time to market, etc. Barge operators nationwide are urging Congress to increase their fuel tax in order to to fund infrastructure improvements—that tax, as well as efficiency improvements that result from local repair or canal widening, will impact costs as well. The cost of a slow-down for the 1.5 - 1.8 million tons annually that would need to move over a separation point may well be exacerbated or ameliorated by these other cost factors. However, questions asked at our advisory committee meeting about the interplay of these factors did not generate robust answers.

The other big variable out there that gets talked about a lot is the widening of the Panama Canal, which should increase the efficiency of waterborne freight movement globally. Speculation abounds that the result could be an increase in "container-on-barge" shipments, some of which could make their way to the Chicago area from New Orleans. However, when asked where investments are being made by smart, profit-seeking individuals looking to cash in on Panama Canal expansion here in the region, the answer was essentially that those investments are not being made. Perhaps it's because there is no real potential for "container-on-barge" in our neck of the woods, perhaps it's because people are uncertain about the prospect of physical separation, perhaps it's something else. Again, no robust answers.

The proper course of action for figuring all this out is, of course, not within a planning effort geared toward stopping invasive species movement. Physical separation may never happen, but freight movement happens every moment of the day. Northeastern Illinois does not have an integrated, intermodal freight plan for itself, let alone one that covers areas of Indiana, Michigan, Wisconsin, and perhaps beyond. That kind of plan would need to focus on the movement of goods, not vehicles themselves, and be mode agnostic. Waterborne freight is currently 3% or so of all freight movement in the region. Could it be more? Yes. Should it be more? We don't know. Randy Blankenhorn, the Executive Director of the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), told the group that our region expects to see 66% more freight movement throughout the region in the coming years, and as of right now we don't have a rigorous plan for capital investments and supportive policies to accommodate that increase efficiently. That's true for rail, road, and air, but especially so for water. Even if water continues to carry only 3% of the region's goods, if the total pie increases 66%, that's a big increase we need to account for.

Our partners at CMAP agree, and have been focusing more and more on freight planning, and may soon be doing even more. It will be interesting to see where the waterways fit in.