Ryan Griffin-Stegink

More opportunities for interaction between IDNR and Lake Michigan permittees would lead to better water management.

Reading through the 43 public comment letters sent to the Ill. Dept. of Natural Resources (IDNR) and posted on their website, I was struck by the frustration and apprehension expressed by most of the authors. As I see it, much of the concern stems from miscommunication. In reality, we’re all working toward the same goals—reducing the needless waste of Lake Michigan water and the money it takes to provide it—and it’s easier to achieve those goals when we work together. At Metropolitan Planning Council’s (MPC) May 7 event, Immeasurable Loss: Modernizing Lake Michigan Water Use, we released a report that details Lake Michigan water loss, supports IDNR’s proposals and provides further recommendations. The goal: better data, better cooperation.

(L to R) Dan Injerd, IDNR; Mike Ramsey, Village of Westmont; Michael Smyth, Illinois American Water

Ryan Griffin–Stegink

MPC is neither a public utility nor a government agency, but we understand the tension inherent in regulatory relationships. When it comes to managing Illinois’ unique access to Lake Michigan water, while still supporting competitive and livable communities, cooperation and recognition of mutual responsibility are paramount. Both regulator and regulated need to do more than just report numbers and enforce targets. Everyone should better understand and appreciate the nuances, processes and effort required to manage individual water systems that share a regional water source. The first step toward that common understanding is to collect more accurate data and truly assess it.

IDNR’s current process for tracking Lake Michigan water use allows permittees to exempt a certain percentage of their lost water, based on pipe miles and age. Labeled “maximum unavoidable leakage,” this reservoir of wasted water precludes an accurate measure of our region's total Lake Michigan water loss. Therefore, we can only say roughly 70 million gallons of Lake Michigan water are lost per day in northeastern Illinois, costing roughly $98 million in water revenue per year. Without accurate data, it simply isn't possible to develop a comprehensive plan for solving the water loss problem.

Setting standards for the use of Great Lakes water is complex. We applaud IDNR’s proposed rule changes as a good first step toward modernizing their rules to better manage the shared resource. Of course, the responses to the changes have been strong. On the one hand, many organizations support IDNR’s proposals, but are pushing for even stronger, conservation-oriented requirements. On the other hand, the municipalities that are the ones most likely to undergo the ramifications may support the changes overall, but are wary of the implications for their operations.

The process of developing MPC’s report really emphasized for me the balancing act we at MPC try to play between all the different players involved. After more than a year spent analyzing data, researching best practices, interviewing experts and considering the whole spectrum of concerns, we have developed nuanced and balanced solutions that reconcile many concerns. Our report breaks down our recommendations into five main solutions:

- Improve the existing accounting system, while exploring a new approach

- Encourage communities to set water rates based on cost and use comprehensive metering

- Require permittees to adopt modern plumbing standards

- Strengthen and streamline outdoor water use standards

- Increase the capacity of IDNR’s Office of Water Resources to provide adequate support to permittees

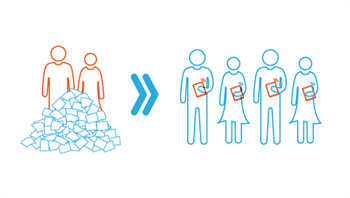

The most common theme I gathered from the comment letters was the need for better communication. Letter after letter began with a detailed story of the problems faced by the community, as well as the successes they’ve had in addressing those problems. These comment letters are possibly the first time some communities have ever engaged with IDNR about their local water management, and they’re probably the most detail IDNR has received about the breadth of programs and challenges out there. It doesn't have to be that way. A critical recommendation in our report is the need to increase IDNR’s capacity so they can create a dynamic and effective space for two-way communication between their office and the permittees. This includes reading and enforcing compliance plans, but it also means providing education opportunities. Communication needs to reach beyond the water managers, as well, to ensure elected officials nderstand the implications of outdated water management models, including the financial benefits of modernizing.

Other specific concerns included a comment from the City of Chicago about the need for “a more nuanced approach” rather than “the one-size-fits-all standard” for reporting water loss. We address this in our report by recommending a move toward the American Water Works Association’s M36 water audit method, which uses an Infrastructure Leakage Index that considers the size of a utility. The Village of Franklin Park echoed a common concern with the comment, “We need a reasonable period of time to bring our domestic water system into compliance. Without a phase-in period, the sudden elimination of the unavoidable leakage allowance will place an extreme and undue burden on us.” We recognize the difficulty of change and in our report recommend that IDNR provide a three-year amnesty period to give permittees flexibility to make the switch.

Arlington Heights and Park City commented on the rule change about outdoor water use, both writing, “The time of day restriction is too strict […] New construction hasn’t been accounted for either. Are we going to let the sod and new grass seed die? What about hand held hoses for water?” We’ve addressed this concern in our report as well. Our year-long project with the Northwest Water Planning Alliance culminated with that group of roughly 80 communities in the northwest suburbs creating a self-imposed shared lawn watering ordinance for their communities that addresses all of these questions.

Much of MPC’s work revolves around trying to find the best solutions and policies by making the most cost-effective use of both public and private dollars. Data-driven decision-making is critical to efficiently allocating finite resources—financial, natural or otherwise—to make the best investments in our infrastructure. The biggest problem right now is that we don’t have the data to create that knowledge, thus we can’t be sure we’re making the best investments. Especially in this era of austerity, that’s neither acceptable nor sustainable.