Josh Ellis

Hamburg's main wastewater treatment plant is a net energy producer, due in part to the biogas produced in these digestors.

For the week of April 22-26, MPC's Josh Ellis was on a tour of water, wastewater, and stormwater industries and utilities with the German American Chamber of Commerce's Midwest office. Stopping in Berlin, Hamburg, and Frankfurt, the group attended trade shows, visited treatment plants, swung by Hamburg City Hall, and more.

Hamburg Wasser's main wastewater treatment plant is net energy positive - it produces more than it takes to run the place. The giant eggs in the background are anaerobic digestors, breaking down sewage waste into methane and residual organic material that is later burned.

I spent the bulk of my time in Hamburg at Hamburg Wasser's main wastewater treament plant, which is remarkable in its own right (as I explore through photos here), but at the end of the day, not that different from other treatment plants. Instead, what struck me most about Hamburg was all the other stuff - stuff I wouldn't typically consider as the core operations of most water/wastewater utilities here in the U.S. - that our hosts believed to be part of their core mission. It's my experience that most water utilities are driven by a goal of selling clean drinking water, while wastewater utilities are driven by a goal of meeting regulatory requirements for discharges into waterways. Those are admirable goals, far from easily accomplished. In the case of Hamburg Wasser (which is the second oldest utility in Europe, trailing only London), however, the goal appears to be true integrated water resources management in the service of Hamburg's broader economic development and environmental protection goals. That means water isn't sold for the sake of selling water, and wastewater isn't treated just because it's required by law, but because potable water (and some non-potable water) are required to run an economy and a city, while wastewater is a great source of resources for energy production, and yes, the quality of discharge to area waterways is a major factor in the integrity of those ecosystems. All told, this represents a divergence from many utilities here.

The boxy building on the left is an incineration plant - that's where the organic materials is burned after biogas has been extracted. The combustion powers turbines, producing more energy, and residual heat is transferred to the harbor facilities in the background, reducing energy demands there. You can just make out a few solar panels on the buildings on the right. There are more elsewhere, in addition to some wind turbines out of the frame.

Josh Ellis

As old as the Hamburg utility is, recent history can explain a lot of this new philosophy. Only a few years ago Hamburg had a standalone water utility, and their job was to sell water. They also had a wastewater utility, and their job was to get rid of relatively clean wastewater. From all accounts, it looked and operated sort of like the relationship between the City of Chicago (drinking water provider, as well as the first part of the wastewater system) and the Metropolitan Water Reclamation District of Greater Chicago (wastewater treatment and discharge). Coordination was a challenge, things like re-use of effluent were a threat to one entity but a benefit to the other, and stormwater management was caught in the middle and not sufficiently addressed. So, a few years ago, those two entities merged. Simple as that. We didn't get into the details as much as I would have liked, but what it boiled down to is that a bunch of smart, concerned people decided that full consolidation of the two enterprises would lead to more efficient, cost-effective and sustainable management of their region's water resources, so they merged. It has paid off.

I openly admit that most of the time up at the top of these things I was thinking about filming a James Bond movie.

Josh Ellis

They started doing all kinds of interesting things once their goals changed. Hamburg relies on groundwater, which is pretty darn cold and relatively clean, so Hamburg Wasser started pumping groundwater to the zoo on its way to treatment plants. It cools zoo buildings, and reduces the zoo's need to buy treated drinking water to do the same thing. Hamburg Wasser deced it wanted to be self-sufficicent in regards to energy, and realized that its waste stream was its single biggest sources of resources for that... enter biogas harvesting, sludge incineration (the scrub the bejezzus out of the emissions, so the only thing going into the atmosphere is water vapor), solar and wind power, heat transfer, and some good ol' fashioned lightbulbs swaps. The utility started bidding on consulting projects to help other countries with their problems, and now have contracts in China, Russia, Rwanda, and Tanzania. And they started working with other city departments on the Jenfield project.

The water self-sufficient neighborhood of Jenfield.

Josh Ellis

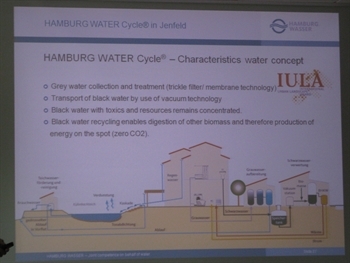

Jenfield is a test case for self-sustained neighborhoods within an exisiting urban environment. A former police barrakcs facility, Hamburg decided to rebuild Jenfield (seen in the diagram to the right) as a way to prove the water-energy nexus can be met, resolved, and managed. Any tap water used on site is recycled as graywater, and any blackwater (sewage) has the waste removed for energy production, at which point the graywater is reused. Rain goes directly to the river (which is tidal, a nice feature, all your stormwater gets pulled out to sea every 6 hours). Add in some other energy production, and voila, a pretty much water and energy neutral neighborhood. I know this is the sort of technology being explored for the redevlopment of the USX site on Chicago's south side, but it's also the sort of thing the Chicago Housing Authority and Public Building Commission should be taking a look at as they continue to build anew in and around Chicago.

I mentioned Frankfurt in the title, and while the main lesson there was "Don't try to compete with Hamburg," some staff from Darmstadt University presented on Semizentral Germany, which is comparable to Jenfield in many regards. While Jenfield is a neighborhood, Semizentral is building modular units that can be rapidly built in developing countries and use potable water and resulting sewage to produce new potable water, non-potable water when you don't need to drink it, energy, caloric heat, and stabilzed waste that can be used as fertilizer. This stuff isn't the future. It's here.

Not everything at Hamburg Wasser was so crazy and different. They put their hard hats on one head at time, just like us.

Josh Ellis

All in all, what impressed me about Hamburg (and to a lesser extent, Frankfurt) was the willingness to reconsider what we normally think of as the provision of water and wastewater services and infrastructure. Hamburg Wasser doesn't exist to sell water - revenue generation is not their primary concern, though the water side generated a 65 million Euro surplus last year, after a 150 million Euro capital investment, and wastewater came out even - they exist to manage water resources in the service of economic development, high quality of life, ecological integrity, and all the other things where having some clean water and clean waterways might be nice. It was refreshing, somewhat startling, and worth the trip.