Photo Credit: Michigan Sea Grant

Low water levels on Lake Michigan near Traverse City, Michigan in January, 2008.

By Abby Crisostomo and MPC Research Assistant Rachel Carnahan

By Abby Crisostomo and MPC Research Assistant Rachel Carnahan - August 19, 2013

Around the Great Lakes, it seems like we have more than enough water to go around. After all, the Great Lakes contain 21 percent of the world’s fresh surface water. However, this vital resource is slowly disappearing from right under our noses. Only 1 percent of the Great Lakes are renewed every year and climate change and evaporation have caused the water level in the Great Lakes to fall a total of roughly five feet in the last decade. At the third workshop of four in the DuPage Water Commission water management workshop series, I learned about practical indoor and outdoor water conservation methods we can use to ease the strain on our natural water supply.

The DuPage Water Commission, Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and MWH Global collaborated to host this workshop series, geared toward public works employees, to get ideas and advice on programs to implement in their municipalities. These workshops are an opportunity for MPC to get involved in DuPage County help public works employees in the region start thinking about water conservation. The first workshop focused on utility planning and asset management in the context of water management operations and the second focused on regulations and ordinances to aid water conservation in the DuPage Water Commission region.

Jared Teutch, water policy advocate at the Alliance for Great Lakes, explained that the Great Lakes basin states, Illinois, Indiana, Michigan, Minnesota, New York, Ohio, Pennsylvania and Wisconsin, are lagging behind western states on our water conservation efforts. He said the biggest reduction in indoor water use could be achieved by mandating efficient appliances, which reduce water use by appliances by up to 50 percent! For outdoor water use, he explained that reducing lawn watering and improving infrastructure would produce the biggest impacts. Improving infrastructure includes capturing runoff, replacing aging pipes and removing the term “wastewater” from the conversation. Wastewater is not actually waste and can be used in a number of non-potable ways. The reuse of this water can decrease the amount of water that needs to be transported to a building, saving energy and money for the utility and customer.

When asked, none of the utilities present had any programs to target their biggest users, non-residential customers. Karl Johnson, Senior Water Resources Engineer at MWH Global, said that typically 30 percent of a utility’s demands are from non-residential customers but are only 10 percent of the total number of customers. This is a huge savings potential for both the utility and the customer. He suggested that the utilities research their biggest users and compare their usage to national benchmarks for their industry. Utilities can then perform an assessment of how customers are using water to identify and target specific areas. In restaurants, for example, the biggest savings come from using trigger-spray nozzles that require you to hold the sprayer, preventing water from constantly running. Targeting the biggest users can be easier than educating residential customers because you only need to reach a few people, instead of the entire customer base. With LEED certification and environmental consciousness becoming a popular marketing tool, many companies have an efficiency coordinator who could be a great source and contact for utilities.

When a utility does decide to work with residential users, one of the best ways is through home water audits. Hillary Holmes, a civil engineer with MWH Global, said that home water audits only take about 20 minutes and show the homeowner what their current water use is, where they have water loss and how they can conserve. The process involves gathering information on household size, how the household uses water and when they use it most; performing the audit by cataloging water-using devices, calculating flow rates, noting existing and finding unknown leaks; and, analyzing the results and determining savings from conservation measures. Or, you can supply the information to the consumer who can enter it into an online calculator to get information on how they are doing and how to improve.

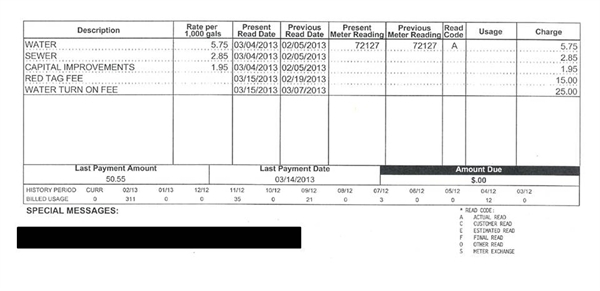

As part of her presentation on residential use, Hillary did an interactive exercise examining how a water bill looks to a customer. Things as simple as changing the units sold to gallons instead of cubic feet or providing a graph of the customer’s past usage can go a long way toward improving understanding of the bill and showing the customer where they can save. Another idea is to provide information on average usage in the community to encourage people to try to use less than their neighbors. Better explanations of fees and what the bill pays for would increase understanding and reduce hostilities toward paying the water bill.

Hillary used this bill as an example. The units are in 1,000 gallons, which doesn't mean much to the customer; it’s nice that the bill includes the read code and key at the bottom to explain where the number came from, but that doesn't really mean anything to the average person either. The bill does separate fees for capital improvements, which provides transparency on where the money is going. The history at the bottom would be much clearer as a graph than as a line of numbers.

Finally, Bill Christiansen, Program Planner with the Alliance for Water Efficiency, discussed their tracking tool for planning and evaluating cost-beneficial water conservation programs. Utilities can input information on their system, baseline demands, demographics and conservation measures into the tool and then model their savings, perform a cost-benefit analysis on various conservation programs, including revenue/rates impacts and energy savings. You can calculate the present value of delayed system expansions and play with different rates to make sure that when demand decreases rates rise enough to cover the utility’s costs.

While some utilities are still skeptical about how they are going to cover their costs when conservation reduces demand, this tool can give them more information on what to expect when conservation measures are implemented and how to select the most cost-effective programs. The discussion of rates and how utilities can conserve without losing money will continue at the final workshop of the series on Wednesday, August 28th.Finally, Bill Christiansen, Program Planner with the Alliance for Water Efficiency, discussed their tracking tool for planning and evaluating cost-beneficial water conservation programs. Utilities can input information on their system, baseline demands, demographics and conservation measures into the tool and then model their savings, perform a cost-benefit analysis on various conservation programs, including revenue/rates impacts and energy savings. You can calculate the present value of delayed system expansions and play with different rates to make sure that when demand decreases rates rise enough to cover the utility’s costs.

The DuPage Water Commission Conservation Series’ last workshop is on water rates and revenue. The half-day workshops are free and open to all public works employees; count for 3.25 Renewal Training Credits through Illinois EPA. For more information, contact MPC Associate Abby Crisostomo.

MPC Research Assistant Rachel Carnahan authored this post.