Chicago Dept. of Transportation

BRT on Ashland would provide economic and community development opportunities.

This post first appeared on Living Cities' The Catalyst blog on Oct. 30, 2013.

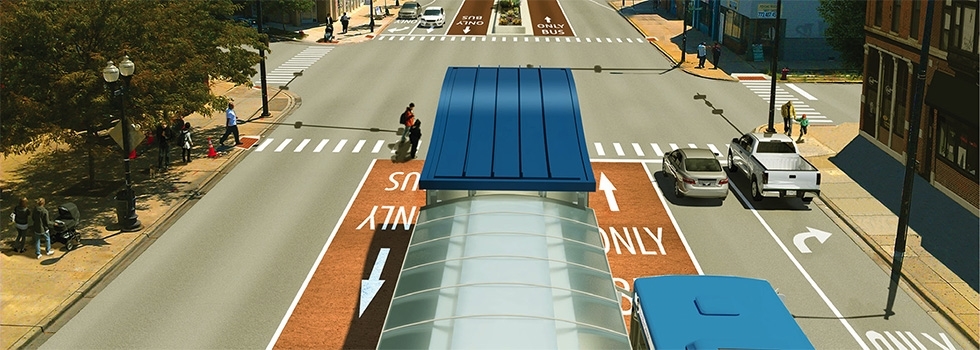

A century ago, Chicago’s electrified street cars sped down (mostly) dedicated lanes on busy commercial streets. Today local buses are stuck in the same traffic as everyone else. Having examined this inefficiency problem with a fresh pair of eyes, Chicago is getting on board with Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), a cost-effective use of existing road capacity that provides commuters with a reliable, fast, affordable and green way to travel. With limited stops and dedicated lanes, as well as permanent, iconic stations and the buses’ ability to sustain a green light until it clears the intersection, BRT has the appeal of rail without the hefty price tag.

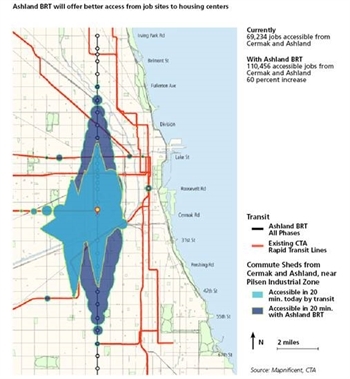

BRT on Ashland would expand access from job sites to housing centers by 60 percent.

Mapnificent, CTA

Making it easier for people to get to jobs, schools and entertainment is just one way BRT supports economic growth. BRT’s connectivity and physical attractiveness also draw a clear map for clustering new public and private investments in communities along the routes. In a report prepared for the National Association of Realtors and the American Public Transit Association, during the recession, home values held up much better in locations near transit. In metropolitan Chicago, prices for homes within a half mile of transit are valued a full 30 percent higher.

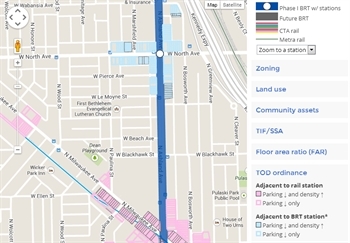

Every city and suburb is seeking low-cost, creative solutions to simultaneously move people to jobs and spark revitalization. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) has become a vocal advocate of Chicago BRT, but for BRT to truly transform a corridor’s economy, it must be paired with transit oriented development (TOD) tools.

The case is compelling. Research from a recently released Institute for Transportation and Development Policy (ITDP) study documents for the first time the type of investment return BRT systems can create. For example, Cleveland’s BRT system, known as the HealthLine, generated more than $5.8 billion in adjacent real estate development in a hard-hit area after it began service in 2008, a roughly $114 return on every $1 invested in building the line. Since then, ridership has increased 60 percent on the route and average speed has increased 34 percent over earlier bus service. In New York, which offers a service similar to BRT, 89 percent of people prefer the new system over the old.

MPC's BRT mapping tool is available at http://www.metroplanning.org/brtmap

To illustrate the impressive return on investment that BRT can yield, Melinda Pollack at Enterprise Community Partners told an MPC Roundtable audience in September, 2013 that municipalities should market TOD tools aggressively and establish ordinances to encourage development along these corridors. She noted that places that have been most successful in attracting private investment have had significant support from the public sector, communicating “we want you here.”

Chicago isn’t just pursuing BRT; it’s pursuing “Gold Standard” BRT to squeeze the most value out of this development generator. And it’s the first city in the U.S. to aim this high. To meet gold standard, Chicago’s BRT service must include dedicated right-of-way, off-board fair collection, at-grade boarding and signal priority.

Meeting gold standard is a daunting but important goal to ensure BRT delivers real travel time savings and reliability, factors that drive the personal decisions of home buyers and renters to locate along transit corridors and attract investors in high-value, residential and mixed-use development. We are watching and learning from places like San Francisco and Denver.

Smart cities and regions aren’t waiting for bipartisan sanity to emerge in Congress. They are pursuing self-reliance and designing their own magnets to transform this economic crisis into an opportunity. The Metropolitan Planning Council understands the challenges and fears that go along with accelerating change. Dedicating a lane of car traffic to transit riders, eliminating many left-turn lanes—these are jarring changes for many. But if we remind ourselves that our roads are for moving people, not cars, and that BRT will move two times as many people on transit as today, the debate suddenly changes.

Running the economic impact numbers is another game changer. For a modest public investment of roughly $10 million per mile, coupled with development financing assistance, vibrant nodes of homes and shops can spring up around stations where today we see vacant land. By showing skeptics how BRT can coordinate public investment and attract private dollars, Chicago could create the first gold-standard BRT in the U.S. and reap the economic rewards of a wise and well-executed investment.