Here’s a basic recipe for a vibrant, livable global city: take an extensive transit system and locate jobs, homes, and multiple amenities nearby. Now consider New York and Chicago, which have bragging rights as the top one and two biggest U.S. transit systems. Which one do you think has added more jobs within a half-mile of transit in the past decade? Which one has more people living near transit today than in 1960? As a Chicago resident, it’s not the answer I would have hoped.

While I am a proud advocate of the Chicago metropolitan region, I am frustrated and embarrassed that we’ve so bungled the chance to generate value from our extensive transit network. Yep, this is the place that has 386 transit stations but hasn’t yet managed to tilt the scale toward clustering office, residential, and retail development nearby to make the most of that asset.

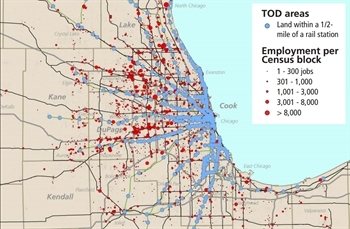

Only 21 percent of the region's jobs and 8 percent of its residents are located within a quarter-mile of transit.

Here are some dramatic and depressing facts:

- while the Chicago region’s population grew 65 percent from 5.5 million in 1950 to 9.1 million in 2010, transit ridership has plummeted by 61 percent, from 1.8 billion annually to fewer than 700 million rides per year

- between 2002 and 2011, the number of jobs located within a half-mile of transit in the Chicago region increased by just 15,000 during a time of sluggish growth; in comparison, that number grew by more than 500,000 in New York during the same time frame

- the number of people living near transit in the City of Chicago has dropped from 1.8 million in 1960 to 1.3 million today.

NOTE: Just 21 percent of the region’s jobs and 8 percent of its population are located within a quarter-mile of rapid transit.

Ironically, fixing this is not a question of residential demand. People in Chicago and nationwide are voting with their feet and their pocketbooks. The National Association of Realtors found that homes located within a half-mile of public transportation were so desirable that they were valued a whopping 41 percent higher than properties located in car-dependent neighborhoods. And no wonder, when those homeowners reap the benefits of living in attractive, amenity-filled communities and may be able to sell a car or even avoid car ownership all together.

But, there is a real tension between affordability and accessibility. The fear is that because this convenient housing located near transit is so desirable, it will push out moderate-priced housing for average working families. Gentrification is a fair concern, but one I’ve become convinced can be overcome.

How? By being intentional about connecting well-designed, mixed-income communities (including housing options for lower-income workers) with clusters of jobs that are currently inaccessible to these individuals, all near transit. This will increase prospects for job seekers while simultaneously expanding the talent pool for employers.

Take the case of two employment corridors located near Ashland Avenue, where Chicago Mayor Rahm Emanuel has proposed the first neighborhood route for “gold standard” bus rapid transit.

One growing employment node is the Illinois Medical District, located a couple miles west of Chicago’s Loop. It is home to four major hospitals and is the destination for 20,000 workers and 75,000 visitors every day. They either compete for limited parking spaces or crowd onto the Ashland bus, the route which carries the highest volume of riders in the city. The Ashland Avenue BRT will speed transit times by 30 to 50 percent and unleash the growth of these anchor institutions.

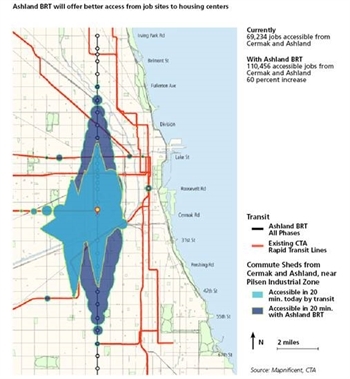

Another high-potential node is the Pilsen Industrial Corridor, one of six industrial corridors that will be served by Ashland BRT. The figure below illustrates that this southwest side zone, which follows the Chicago River, will then be accessible to 50,000 more adults within a reasonable 20-minute transit trip. Growing businesses like the Chicago International Produce Market—a Terminal Market that is home to 22 produce purveyors including some third- and fourth-generation companies—will benefit from greatly improved access and talent.

So let’s return to that recipe for a healthy region. Connecting good jobs and reliable transit is a key ingredient. So is attracting investors and developers who can execute on equitable development. Achieving this vision will require beefed-up incentives to encourage clustered mixed-use development in optimal locations.

The City of Chicago took an important first step with a new Transit Oriented Development ordinance passed in fall 2013. It allows for reasonable increases in density and cost-saving reductions in parking requirements for specific parcels a quarter mile from Metra or CTA rail stations. At least one proposed development, steps away from the Paulina Brown Line station, is making use of this new tool.

Cities like San Francisco—where 41.2 percent of jobs are within a half-mile of transit compared to only 31.6 percent in the Chicago region—have taught us that we must go further. The Metropolitan Planning Council will be working simultaneously to: strengthen the TOD ordinance’s incentives; explore development financing that supports TOD; map and market available parcels and work with the Cook County Land Bank to ease acquisition; and partner with hospitals, universities, and manufacturers on live-near-work-and-transit benefits.

These proactive steps will have measurable payback. Our ultimate success will be measured in expanded choices. Do moderate-wage workers have access to affordable homes near their jobs and transit? Do commuters have real choices about getting to work within a reasonable time? Have anchor institutions been strengthened by a bigger labor pool and more attractive campuses? By jointly pursuing accessibility and affordability, we’re on a path to answering yes.

This post originally appeared on the Meeting of the Minds blog on March 31, 2014.