Only 21 percent of jobs and 8 percent of residents are located within a quarter-mile of transit.

Expanding commuter options opens doors for residents

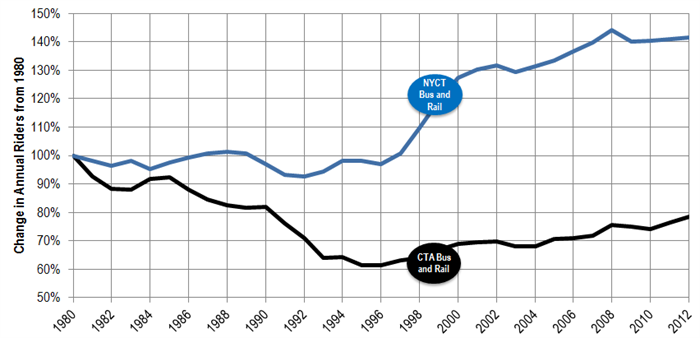

Almost every day, The Atlantic Cities features an article about the trendiness of transit and the lure of city living. And yet, Chicago’s urban transit network attracts 20 percent fewer people today than it did in 1980. Compare that to New York City, where their transit system attracts 40 percent more people than in 1980. Meanwhile, single-occupancy car trips in the Chicago region were up 5 percent between 1990 and 2008.

Chicago transit ridership (black line) since 1980, compared to New York City (blue line).

In the Chicago region, the problem isn’t only one of sustainability. Only 21 percent of jobs and 8 percent of residents are located within a quarter-mile of transit. And property values near transit higher than average. The result? People without cars who must rely on transit are often priced out.

Chicago is a fascinating case study among multiple metros that are juggling new patterns of living and commuting. Some challenges are inherent in local policies. Others are social or cultural, requiring uncomfortable conversations about poverty, race and segregation. Other barriers stem merely from a lack of communication or education.

The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), an independent organization that develops solutions to problems that hinder growth in the Chicago region and every region, applies a mixture of long- and short-term tactics to address accessibility and affordability. By partnering with businesses, governments and communities, we advance a vision of a more interconnected Chicagoland, where every resident has convenient access to a wide array of regional jobs.

Getting the rewards right is one key long-term ingredient. Chicago’s new transit-oriented development (TOD) ordinance begins to offer the incentives to attract developers building closer to transit, though it could go much further. But we need to ensure that TOD across the region does not exclude the residents who need it most. How do we provide for these residents? By connecting well-designed, mixed-income communities (including housing options for lower-income workers) with clusters of jobs that are currently inaccessible to these individuals, all near transit. This will increase prospects for job seekers while simultaneously expanding the talent pool for employers.

Another critical ingredient is improving transit near clustered development. Chicago’s plans for bus rapid transit (BRT) along Ashland Avenue, a major north-south arterial, will connect more than 31,000 daily riders with job centers like the Illinois Medical District on the near west side. The District is home to four major hospitals and a daily destination for 20,000 workers and 75,000 visitors. BRT is cheaper to build than train lines and, in an era of tight budgets, provides a feasible solution to connecting people and jobs, speeding transit times by 30 to 50 percent along Ashland.

But despite Chicago’s plans for BRT and the TOD ordinance, demand for convenient, attractive homes near transit will continue to far outstrip supply. And many job centers are in the suburbs, inaccessible today by public transit and, therefore, by potential lower-income workers without cars. While retrofitting our transit network is the long-term answer, how do we address the accessibility question in the short term?

Through improved and expanded Commute Options. By increasing the number of ways employees can get to their jobs, we increase the workforce pool. Commuters who aren’t forced to drive solo will reduce the amount they pay for gas. Less traffic on the roads will shorten commute times, and time is money. Whether by providing special shuttles to hard-to-reach suburban job centers, or offering emergency ride home programs for employees who choose not to drive, employers can be a part of the short-term solution.

Grainger, an industrial supplier employing around 2,600 people at three suburban locations, participated in MPC’s two-year Commute Options pilot. The company’s Lake Forest campus created a dedicated shuttle to the nearest Metra station, instituted an emergency ride home program, and promoted pre-tax benefits and ridesharing. The results were spectacular: Drive-alone rates dropped 20 percent as transit use and ridesharing rates doubled. Of employees who switched to an alternate mode, 68 percent reported saving money—an average of $151 for gas, tolls and car maintenance every month.

More transit-oriented development is the answer to many of our region’s current challenges, especially the job accessibility gap. However, any effective TOD plans must make provisions for those who cannot afford high rents and for whom transit is not a trendy choice, but a necessity. Only by catering to all of its residents can Chicagoland become a truly world-class region, with a diverse and mobile population. Long-term, we must make dramatic changes to achieve accessible, affordable development near transit.

In the short term, the good news is that we have plentiful options to improve job accessibility. The Chicago region can lead the way in connecting people to jobs.

This post is part of a group blogging response to Meeting of the Minds' and Living Cities question, How Could Cities Better Connect All Their Residents to Economic Opportunity? Check out all of the posts here.