Northeastern Illinois has unique water supply and use issues - every region does. That's why a statewide framework for regional water supply planning will help us develop specific plans for specific circumstances.

This October (and in September, much like real Oktoberfest) the Metropolitan Planning Council’s Josh Ellis is speaking at four conferences about different aspects of MPC’s water resources management work. At the same time, the Johnson Foundation at Wingspread recently culminated six years of its Charting New Waters program, releasing a vision and set of guiding principles requiring “collaborative leadership across sectors and scales.” As Josh explores throughout this series, MPC and its partners are realizing that vision here in northeastern Illinois, with lessons that can be brought to bear well beyond the banks of the Fox River and the shores of Lake Michigan.

Last week I was down in New Orleans focused on stormwater issues at WEFTEC. This week I had the great fortune to be one of the keynote speakers at the Michigan Association of Planners’ Annual Conference on Mackinac Island, where I gave a talk I called “Taking the Long View: Institutionalizing Adaptation in Water Supply Management.”

The invitation to come to Michigan came with a couple of specific requests – talk about climate change, talk about Illinois’ experience with regional water supply planning and share some lessons Michigan can learn from Illinois. Can do.

It’s been a decade since the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) really entered the fray on water supply management policy. As an outgrowth of the successful Campaign for Sensible Growth, and in close partnership with Openlands, between 2004 and 2009 we authored a series of reports – Changing Course (2004), Troubled Waters (2006) and Before the Wells Run Dry (2009-and note the optimism, as lots of people since then have mistakenly called it When the Wells Run Dry). Taken together, these reports helped set the stage for a lot of the changes we’re seeing in water policy in northeastern Illinois and throughout the state.

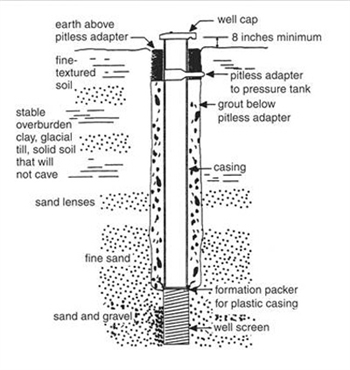

Mandated annual reporting of all high-volume wells in the state? Came straight out of Changing Course. Alternative wastewater treatment systems? That’s what we call water reuse and resource recovery now, and in addition to being the focus of a recent roundtable, it was also a recommendation of Troubled Waters.

Thanks to legislation MPC and Openlands helped craft and pass, all high-volume water users in the state must report annual consumption.

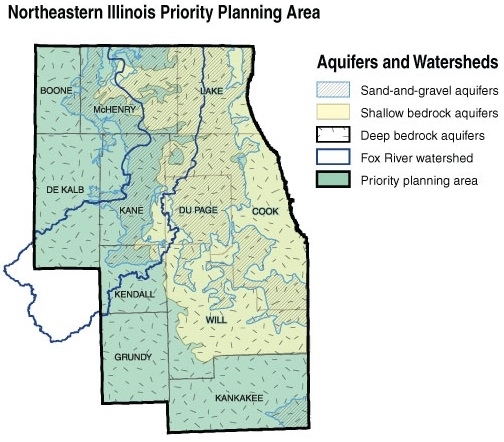

Likewise, the first call for a statewide framework for regional water supply planning, which led to Executive Order 2006-01 and the creation of two pilot regional water supply planning groups in northeastern Illinois and the central part of the state. (A third regional water supply planning group, in the Kaskaskia basin, was established later). As a result, the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning issued Water 2050, our region’s first real water supply and demand plan, in 2009. However, because the state did not develop a plan to create, fund and support regional water supply planning groups across Illinois, as directed by the 2006 Executive Order, MPC and Openlands issued Before the Wells Run Dry, which outlined a vision for what that statewide framework for regional water supply planning should look like (see page 34 of this hefty report.)

Flash forward to 2014 for a progress report: Over the past few months, the Ill. Dept. of Natural Resources has allocated nearly $1.6 million to support implementation of the three existing regional water supply plans, start a few more, beef up its own staff and the Illinois State Water Survey’s, and develop a draft action plan for finally establishing a system that on paper looks a whole lot the one we detailed in Before the Wells Run Dry.

This is all great progress.

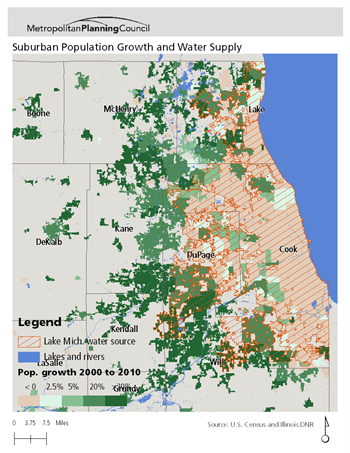

But what does it have to do with climate change and institutionalizing adaptation? Well, the whole premise behind regional water supply planning groups was to foster a structured dialogue between relevant stakeholders, state agencies and scientists, to learn from each other, react to new information and structure policy change. The issues of the day continue to evolve: how changing precipitation and temperature patterns will affect water supplies (or, just as likely, affect something like evaporation rates, which affects agricultural practices, which affects water supplies); shifting population trends; fracking; seasonal drought; groundwater contamination; new Great Lakes policies; water reuse. The world is constantly changing, and those changes have unique affects in different regions and on different stakeholders—so by bringing regional stakeholders together, we can forge solutions that work.

Climate change isn't the only reason for long-term water supply planning (though it's a pretty good one), population shifts have a major impact on water resources well.

In northeastern Illinois the predominant group of water managers are public, municipal water suppliers (i.e. city and village utilities), but they are much less prevalent downstate, where agriculture, power production and even investor-owned utilities are more common. So, our region would tend to focus on issues affecting and affected by municipal water consumption, but not to the exclusion of agricultural, industrial or ecological concerns. Any given regional water supply planning group would reflect that region as a whole, and establish water usage priorities, determine needed research projects, and hopefully in time, be able to influence regional prioritization of state funding programs, such as the Clean Water Initiative (that’s how it works in Texas).

The whole planning process is designed to be iterative and ongoing, tracking and foreseeing change at the same pace that change occurs. That’s always been MPC and Openlands’ vision for regional water supply planning–institutionalized change agents with sufficient structure to align adaptation with on-the-ground (or in the sky or underwater) conditions.

There are only a handful of states that have a statewide system of regional water supply planning, and yes, Michigan and many other states would stand to benefit from moving down that path. Building regional consensus and advising the state on regional priorities can help with conflict resolution in times of drought or shortage (and maybe even help forestall those conditions. It also can raise awareness about new technologies, like systems for on-site treatment of non-potable water, and how they may or may not help with water management goals. Michigan, for example, actually has lots of great data collection systems in place for tracking water supplies, so it has a great head start if this is a path it pursues.

Ultimately, this is all about optimizing the management and use of available water supplies, which is also one of the pillars of the recent Johnson Foundation report. Some of that optimization can come through use of new technology and plain old repair of leaky pipes, but some of it can also come from consistent, informed dialogue between regional stakeholders, between regions and the state, between state agencies, and ultimately between all those folks and the rest of us. If we can stay on top of the science, and stay on top of external forces beyond our control, climate change included, we stand a much better chance of being able to guide at least some portion of our collective water fate. The good news is, Illinois is closer than ever to creating a statewide framework for regional water supply planning, and it’s exciting to help lead that change.

Next stop: Illinois Water 2014 in Urbana-Champaign, to talk about progress made since MPC’s groundbreaking Immeasurable Loss, which explored for the first time in detail the need to modernize our state’s management of Lake Michigan water.