Daniel Kay Hertz, with original data and research from Sean Reardon and Kendra Bischoff

For all the ink that’s been spilled on the creation of mixed-income communities in Chicago, the truth is we’re not mixed. Not by a long shot. Most of Chicago is either poor or rich, and Chicagoans can count on one hand the neighborhoods that stand in contrast: Hyde Park, Rogers Park, Albany Park, Uptown as of 5.27.15 and...well, like we said, it’s not a long list.

It sounds obvious to say, but we’ll say it anyway: Economic segregation concentrates not only the poor, but also the wealthy. The growth of concentrated poverty on the city’s South and West sides and the decline of Chicago’s middle class means that other areas must in contrast have concentrated wealth.

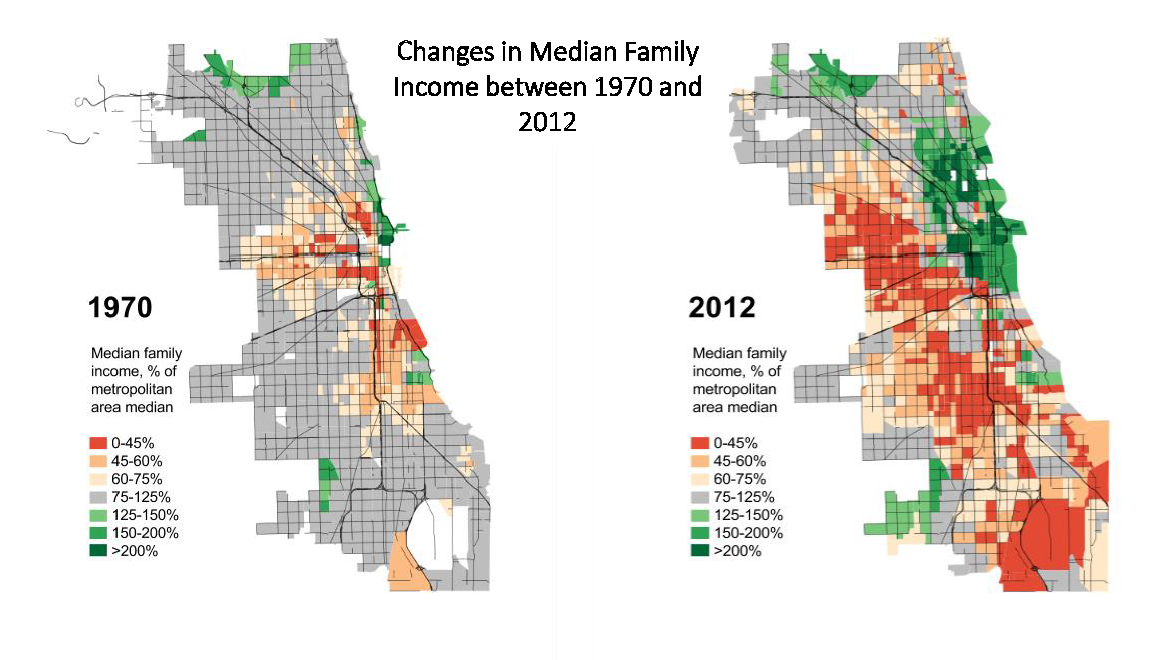

The maps above show that while areas of concentrated poverty grew tremendously from 1970 to 2012, so too did concentrated affluence. Nationwide, Reardon and Bischoff note that the segregation of affluence is even higher than the segregation of poverty, and the affluent are increasingly distant even from the middle class.

If you find yourself asking “so what?” at this point, you are not alone; concentrated wealth has been idealized more than problematized in the public view. But keep reading.

One downside of high levels of concentrated affluence is decidedly squishy. It’s called a lack of “social empathy”—the idea that you are less likely to understand or support investment in policies or programs for the poor if you never cross paths with them. While the impact of this phenomenon is difficult to measure or quantify, we need only look to recent events in Baltimore and Ferguson for clarity. The 24-hour news coverage in both cities starkly revealed the discrepancies between how people of different races experienced and interpreted the death of a young African American man at the hands of law enforcement and the unrest that followed.

In some ways this isn’t surprising: Data from the Public Religion Research Institute’s 2013 Values Survey revealed that the social networks of whites are 91 percent white and 75 percent of whites have entire social networks without any minorities. So while social empathy is an academic, seemingly amorphous term, we’ve been shown the impact of its absence when the minority poor and the white wealthy occupy extremely different worlds within the same city.

In contrast, a second negative of the isolation of the rich is all about the numbers: 2013 Urban Studies research led by Harrison Campbell found that

"when poverty rates and segregation are high in metropolitan areas, those regions perform worse economically relative to less segregated places. Regions segregated by race as well as skills have slower rates of income growth and property value appreciation. And this isn’t just true for minority families stuck in segregated pockets of inner-city poverty. It's true for everyone."

The impacts of concentrated poverty are to some degree more tangible, visible and often tragic. Anti-poverty programs tend to focus on fixing poverty in place, from high crime to low educational and employment outcomes. Noting this tendency, Reardon and Bischoff point out that we “routinely commit the outdated fallacy of assuming that concentrated social problems must have local causes.” When we focus on the ills of segregation only in non-white, low-income neighborhoods, though, we ignore the impact of the other end of the spectrum, such that, as a University of Minnesota study found, we think white segregation is normal.

The impacts of concentrated wealth, in contrast, are harder to immediately discern, play out over a longer term and involve less tangible, more macro-economic impacts. Consider the picture this CityLab article paints:

“Metropolitan economies rely on labor of all kinds, often side-by-side, with high-end architects alongside plumbers, office towers near cab stands, and biotech inventors with security guards. But when low-wage workers pay an out-sized chunk of their paycheck just getting to work, or when suburban office parks locate beyond the reach of public transit, those inefficient patterns start to affect whole regional economies.”

These trends, perhaps innocuous in isolation, play out negatively on the macro scale. When the wealthy concentrate, they contribute to trends that harm the region economically. Campbell describes it as a kind of market failure in which “what seems to be good for the individual turns out not to be good for society as a whole.” Consider recent research from Harvard University highlighting that commuting time has emerged as the strongest factor in determining whether a person escapes the cycles of poverty. When people can’t connect to jobs, it not only hurts those individuals but also the overall regional economy.

What does this look like in Chicago? Research from the University of Minnesota defines racially concentrated areas of affluence as census tracts where 90 percent or more of the population is white and the median income is at least four times the federal poverty level, adjusted for the cost of living in each city. With 58 of these racially concentrated areas, Chicago ranks third on the list of cities with isolated wealth, just behind Boston (77) and Philadelphia (70), while the sample average was 32. This isolation is reflected in research on Chicago’s public schools, which found that only 25 percent of students in Chicago are white, but 67 percent attend a majority white school.

It’s worth a side note that diverse cities are often the most segregated, as Nate Silver recently argued. He uses Dustin Cable’s interactive “Dot Map” of racial residency patterns to prove what Chicagoans live everyday: While Chicago is very diverse at the macro level, at the neighborhood level it is quite the opposite. In fact, cities with substantial black populations tend to be highly segregated. While Chicago scores as the most segregated in the country, he found that most cities east of the Rocky Mountains with substantial black populations have high levels of segregation.

We are subsidizing Chicago's separation.

Let’s say we could agree that this hyperseparation of both the poor and the rich is a bad idea. What now? Given the similarities between Baltimore and Chicago, what lessons can we learn? That University of Minnesota study we referenced earlier points in an interesting direction: They found that in the Twin Cities, federal housing dollars are spent equally across areas of wealth and areas of poverty. In low-income areas, federal investment comes in the form of housing vouchers and subsidized units. In wealthy areas, the mortgage-interest deduction provides the lion’s share of housing subsidy. In Chicago, where most affordable subsidized housing is on the South and West sides and rates of homeownership are highest in wealthy areas, it is clear that we are subsidizing our separation.

What if we worked harder on integration instead? Here at the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), we’ve been working on a range of efforts to spur healthy, mixed-income communities. For a decade, we’ve been working with nine regional housing authorities through the Regional Housing Initiative to provide subsidies for affordable housing in low-poverty communities near transit and have supported 28 developments to date. Similarly, we are encouraged by recent changes to the city’s Affordable Requirements Ordinance, which will result in more affordable housing where it’s been lacking: in otherwise market-rate buildings in high-income communities.

The Chicago Housing Authority is increasingly partnering with developers in profitable real estate markets to place public housing units in North Side neighborhoods where they’ve long been absent. Chicago TREND is embarking on an ambitious strategy to bring retail to underserved communities, thus better serving existing residents and increasing the likelihood of attracting new. These are small tools in a toolbox that needs expanding, but they’re a start. Instead of subsidizing our separation, let’s work harder on developing more strategies for integration.