Daniel Wolf

My (Daniel's) dissertation supervisor of last year, Alison Duffy, inspects a detention basin in Dunfermline, Scotland. "I think it's bonnie!" she declared despite its less than perfect maintenance record. Similar issues occur in the Chicago Area.

By Josh Ellis and MPC Research Assistant Daniel Wolf

By Josh Ellis and MPC Research Assistant Daniel Wolf - June 1, 2015

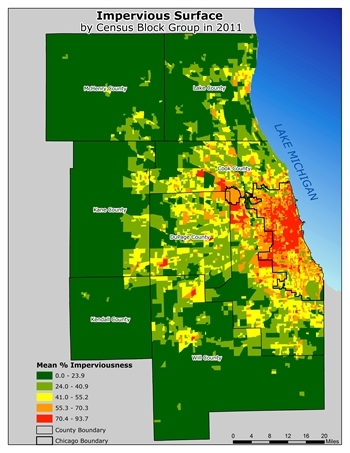

"About 40 percent of Cook County is now impermeable, so that means there's more water that's competing to get into local sewer systems," says Metropolitan Water Reclamation District President Mariyana Spyropoulos. “Rain barrels and other green infrastructure can help capture that water."

Daniel Wolf

Dark green indicates lush, vegetated surfaces, which are ideal for soaking up stormwater. Orange and red reveal where the ground has been paved over—a recipe for urban flooding. Source: National Land Cover Database

We know that green infrastructure offers solutions to flooding in Chicago-area communities, but information doesn’t always reach the people who can build it. Gray infrastructure, consisting of massive concrete pipes, pumps and underground tunnels, tends to be the go-to solution for stormwater engineers and municipal officials. But it’s vastly expensive and it can cause environmental problems. Using plants, rain barrels, porous pavement and other cheap, simple technologies (known collectively as green infrastructure) is an effective yet underutilized approach. Recently in the northwest Chicago suburb of Schaumburg, at the American Public Works Association Chicago Area Expo, I had an opportunity to discuss these issues with representatives from Chicago-area communities. I also got to trade lessons learned about stormwater management during my master’s dissertation in Scotland.

American Public Works Association Chicago Metropolitan Chapter

My presentation on cost-benefit analysis of sustainable urban drainage systems in Scotland had audience members spellbound.

Enormous, salt-sprinkling snow plows, leaf vacuums and lawn mowers were just a few samples of the hardware on display at the convention center. Equipment operators, foresters, engineers, municipal officials and at least one water resource planner were among the attendees. I watched a presentation about remote controlled water pipe cleaning robots and chatted about invasive insects over lunch with a tree trimming crew. Public servants from suburbs such as Wilmette, Elmhurst, Downers Grove, as well as the city of Chicago, came to see my presentation and to participate in the discussion I led. I was intrigued to hear that people are having many of the same experiences with their green infrastructure in Chicago area communities as they are in Scotland.

American Public Works Association Chicago Metropolitan Chapter

Equipment operators show off their skills on an obstacle course as part of the Front End Loader "Roadeo" event.

For one thing, it isn’t always clear whose responsibility it is to maintain urban wetlands or green roofs years after they’ve been installed. At my study site in Scotland, I found that in many cases a real estate developer builds a pond or wetland, the land gets sold to a local government agency, a landscaping company gets contracted to do maintenance and amid the confusion the water features fall into disrepair. A few public agencies in Chicago have experienced something similar.

Some of the situations involving green infrastructure may be unique to the Chicago area. Many of the best sites for green infrastructure are on private land, in the backyards of homeowners who sometimes need some convincing in order to install water management features— especially when the people reaping the benefits of one person’s rain garden may be the neighbors down the block who get to enjoy a dry, flood-free basement.

One tool for balancing these incentives is the stormwater utility fee. Homeowners pay into a fund based on how much of their property is covered by pavement or rooftop (which generates stormwater runoff) and they get paid back for investments in green infrastructure (which absorbs stormwater runoff). The Village of Downers Grove has been using a stormwater utility fee since 2012; more recently the City of Elmhurst has begun a reimbursement program for stormwater retrofits, but so far not many homeowners have been taking advantage of it.

The Metropolitan Planning Council has been working with municipal officials and homeowners in order to clear some of the hurdles preventing more widespread use of green infrastructure. Our Logan Square Corridor Development program allocated Illinois Green Infrastructure Grant funds in order to install features at 12 residential properties. Our work with Calumet Stormwater Collaborative promotes sharing information among authorities, so that green infrastructure gets maintained regularly and correctly. My case study in Scotland can help our region manage stormwater more effectively too. Still left on my list of Scottish things to promote in Chicago are bagpipes, lawn bowling and haggis. I have my work cut out for me!