Clayton Ballerine, Illinois State Water Survey

By Momcilo Markus

By Momcilo Markus - July 28, 2015

Chicago is having ongoing problems with flooding. Heavy storms are more frequent and stronger than those used to design the existing urban drainage infrastructure, and as a result, the system often fails to keep up with these storms. Not only is the infrastructure inadequate, but an apparent increase in the number of heavy storms and floods in the recent past means it could become even more inadequate over time.

Why is drainage infrastructure in Chicago inadequate?

Heavy storms are random. Changes in storms are expected from year to year, from decade to decade, and storms even vary for different multi-decadal periods. Drainage infrastructure in our cities is designed to handle large storms of a predefined magnitude and duration, called the “design storms.”

However, these 1961 standards underestimate heavy rainfall events because they were based on an unusually dry record between 1900 and 1958.

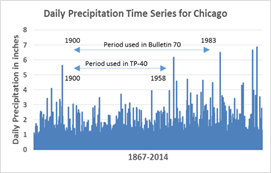

One of the frequently used design storms in Chicago is the 2-hour 10-year storm, defined as the amount of rainfall that is likely to fall in 2 hours once every 10 years. Consequently, a pipe system designed for this storm will be overwhelmed by a 2-hour rainfall once in 10 years on average, resulting in flooding. Significant portions of the urban drainage infrastructure in Chicago were designed to handle this design storm determined by the U. S. Weather Bureau (presently National Weather Service) Technical Paper 40 of 1961. However, these 1961 standards underestimate heavy rainfall events because they were based on an unusually dry record between 1900 and 1958 (Figure 1). These unrealistically small drainage standards and the resulting undersized drainage infrastructure explains our frequent flooding. The standards used before 1961 were based on the earlier parts of the same record and were not much different, suggesting that older drainage structures were also undersized.

Figure 1. A composite daily precipitation time-series for Chicago between 1867 and 2014 (based on data prepared by Dr. Nancy Westcott, Illinois State Water Survey).

To account for larger storm events after 1958, the Illinois State Water Survey produced a revised precipitation analysis, Bulletin 70, in 1989. This bulletin used a longer historical period than Technical Paper 40, and included dry and wet episodes, producing higher and more realistic standards. However, since large portions of the drainage infrastructure in Chicago were built prior to 1989, it is safe to conclude that their inadequate capacity is the primary reason for frequent flooding in Chicago.

Will floods become even more frequent?

Selecting the right technical bulletin to design urban drainage infrastructure is not the only challenge related to urban flooding. Statistical calculations used in drainage manuals (such as TP-40 or Bulletin 70) assume that rainfall can vary due to its random nature, but the basic statistics do not change. The problem arises when the statistics change.

Historically, the Chicago region has been hit many times by extreme rain storms that cause significant flooding. However, these flood events are becoming more frequent. At many places in the region, the 10-year storm has been exceeded multiple times in the past five to 10 years, leading many Chicago residents to remark, only somewhat facetiously, that a 10-year event occurs every year. This public perception, although exaggerated, is mainly supported by data. Figure 2 shows a recent increase in the number of heavy rainfall events in northern Cook County, which is consistent with trends observed in other areas of the Midwest. Many climate studies indeed suggest that heavy storms in Chicago are likely to intensify in the future.

Figure 2. Average number of times a 2-hour 10-year rain storm occurred in a 10-year period, based on observations at 12 rain gages in Cook County.

Do not ignore future rainfall uncertainty—account for it!

While most monitoring data and research indicate that the intensity and frequency of heavy rainstorm events have been increasing and are likely to continue to increase, it is not exactly known if it will actually happen, and if it does, to what degree. In fact, while a majority of climate models project future increases in heavy rainfall in the Chicago area, some models for some climate scenarios project decreases. This uncertainty is significant, and many of us tend to use it to simply ignore the projections of future precipitation. However, ignoring a potentially big change just because it is uncertain could be very costly.

Accounting for the uncertainty instead of ignoring it would be more prudent. It would give us a range of possible heavy rainfall events, along with their probabilities. This range could serve as a tool for urban managers to adopt somewhat more stringent urban drainage standards by applying suitable safety factors. As our climate models become more sophisticated and more accurate, and as we collect more observed data, we will be able to fine-tune our future rainfall and flooding projections.

Presently, the Illinois State Water Survey researchers are conducting studies to update precipitation estimates in the Chicago area, and to determine how they are affected by a range of climate projections. A key focus of these studies is to properly account for uncertainties based on data, modeling, and climate projections, which will provide confidence limits for these estimates.

Dr. Momcilo Markus is a hydrologist at the Illinois State Water Survey, faculty member at the Department of Agricultural and Biological Engineering and the Department of Natural Resources and Environmental Science at the University of Illinois, an associate editor for Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology and a Fulbright specialist. His current work includes studies on past and projected climate changes, and their effects on rainfall frequency and urban flooding.