Flickr user Don Harder (CC)

JCDecaux's partnership with the city to construct and maintain bus stops in exchange for advertising privileges is an example of a successful public-private partnership.

There exists a social contract between government and the public to provide infrastructure for the people. This contract finds its roots within the U.S. Constitution’s commerce clause to provide post roads and dock-yards, the precursors to today’s highways and ports.

Today, that contract is broken.

It’s been in breach for the last several decades, with both sides failing to live up to their end of the bargain. The good news is, there is a new approach to fulfilling this contract: the public-private partnership for delivering infrastructure. This model uses private sector expertise to design, build, maintain, operate and finance a given piece of infrastructure over a finite time period.

Considering the state of our roads and transit systems, paired with public sentiment, these partnerships may be the only solution to maintaining resources that are reaching the end of their useful life—many of them, throughout the country, at exactly the same time.

Nationwide, and particularly in Illinois, government has failed to keep up with necessary improvements to our transportation infrastructure, deferring maintenance to the point where only 60 percent of Illinois roadways will be in good shape by 2021—costing the average driver nearly $300 in repairs per year.

It has been politically expedient to divert monies set aside for the maintenance of infrastructure (a long-term investment) to the immediate funding of programs in the annual budget. To compound the problem, the gas tax, Illinois’ chief source of transportation funding, has been in decline for decades. Set at 19 cents per gallon in 1991, the purchasing power of this flat tax has eroded to the equivalent of 10 cents in 2016. Put another way, had the 19 cents kept pace with inflation, we’d be paying closer to 36 cents per gallon at the pump today.

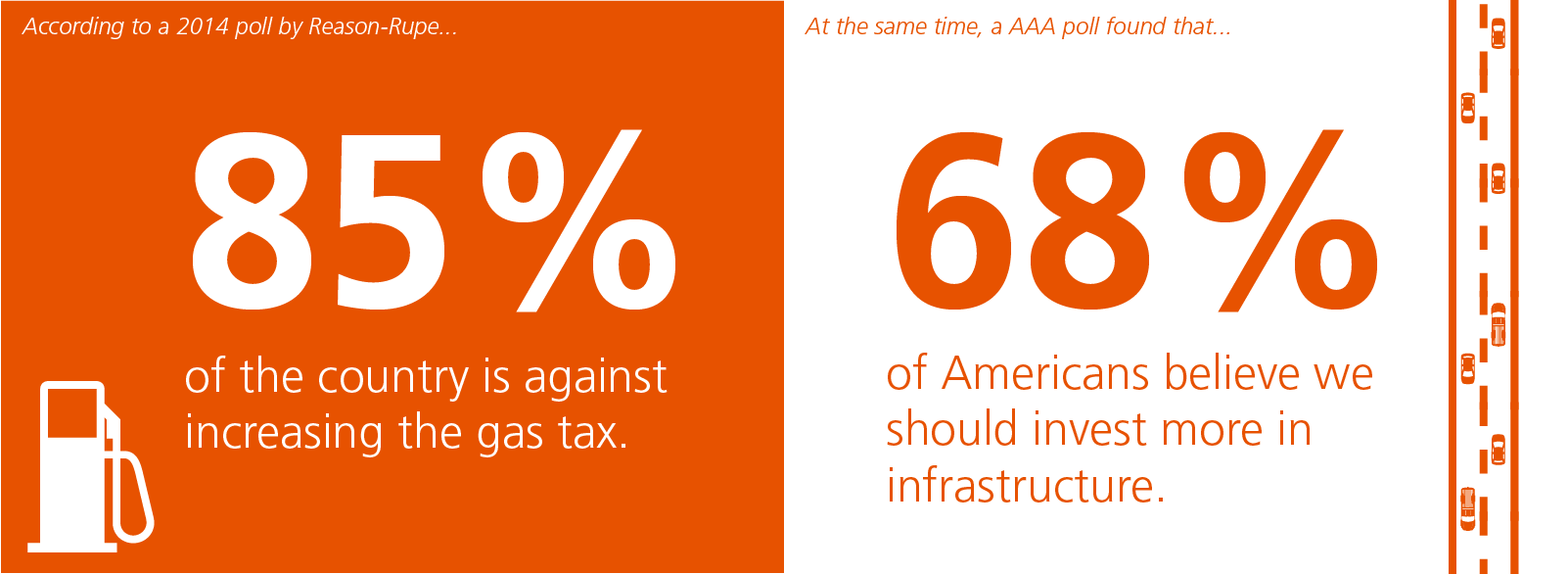

So while public poll after public poll ranks investment in infrastructure high on the list of public priorities, sentiment for an increase in the gas tax remains extremely negative. According to a 2014 poll by Reason-Rupe, 85 percent of the country opposed an increase in the gas tax. At the same time, a AAA poll found 68 percent of Americans believe we should invest more in infrastructure.

It is clear there exists a large disconnect between the public’s appreciation for roads, bridges, trains and the like and their willingness to pay more for them. One way to bridge this gap for some projects is through a public-private partnership.

This model essentially replaces the social contract with a legal one. Typically, the public body issues a request for proposals to deliver a piece of infrastructure in exchange for payments over time. This legal contract requires the private actor to cover all cost over-runs, construction delays and maintenance, and to deliver the product in a state of good repair at the end of the lease.

Let’s use a road as an example: A private firm designs and builds a toll lane in each direction on the Stevenson Expressway outside Chicago. It maintains the lanes regularly for the duration of its 50-year lease, collecting its income from toll revenues. At the end of the lease, the firm turns the lanes over to the public looking like new. The public gets these toll lanes for no additional cost.

When was the last time government guaranteed there would be no cost over-runs on a construction project? When has government done a good job of yearly infrastructure maintenance? To be sure, it happens. The Toll Highway Authority is a good example of sound budgeting. But it’s more often the exception than the rule. Illinois surface transportation infrastructure would not be in the state it’s in if that were the case.

While public-private partnerships can provide many benefits in a tight fiscal climate, they shouldn’t be used for all projects; they fit best for projects that are part of a regional plan and are fully vetted through that process.

And as Chicago can attest, these partnerships can go wrong. It’s important for governments to ensure they’re getting the most out of the deal.

Public-private partnerships are not an end unto themselves and should not be unchallenged. But they are a way to deliver essential infrastructure projects that the public has vetted and determined necessary. Where they are appropriate, the partnerships ensure projects are delivered in the best possible manner for the public at the most competitive cost.