Flickr user Premier Photo (CC)

Ephebiphobia, the fear of young people, is a well documented phenomenon in urban planning.

It’s taken as a general truth that our elderly population is swelling. Much ink has been spilled on the “Silver Tsunami,” the impact that the baby boom generation is creating as it gets older. In the city of Chicago, however, the number of people aged 65 and over actually decreased by 20,871 from 2000 to 2010. Because we lost population overall during that decade, the percentage of Chicagoans over 65 remained the same: 10.3 percent.

Yet, there is undoubtedly need to affordably house our aging population: The U.S. Census American Community Survey estimated that by 2014, nearly 70 percent of Chicagoans aged 65 and over would be at or above 150 percent of poverty level ($17,505 for a household of one). And nationwide, the need breaks disproportionately along racial lines: A recent Aging in the United States report found that just 8 percent of whites 65 or older lived in poverty in 2014, but 18 percent of older Latinos and 19 percent of older African Americans were poor. Relatedly, African Americans and Latinos are much more likely than whites to rely on Social Security for income during their retirement.

So please hear me saying that we need affordable housing for seniors. Because now I have a couple questions: Is the supply of affordable senior housing proportionate to seniors' share of Chicago’s low-income population? If not, why aren't we building more affordable housing for other needy groups, such as families and those needing supportive services?

As the Chicago Rehab Network noted in its 2013 analysis of the City’s fourth Five-Year Housing Plan, from

2009 to 2013, just over $1 billion was spent to create or preserve 3,982 units of affordable rental housing in Chicago. Of those, 42 percent were for families, 39 percent were for seniors, 11 percent were Single Room Occupancies, 7 percent offered supportive services, and 1 percent were for artists. The Rehab Network points out that:

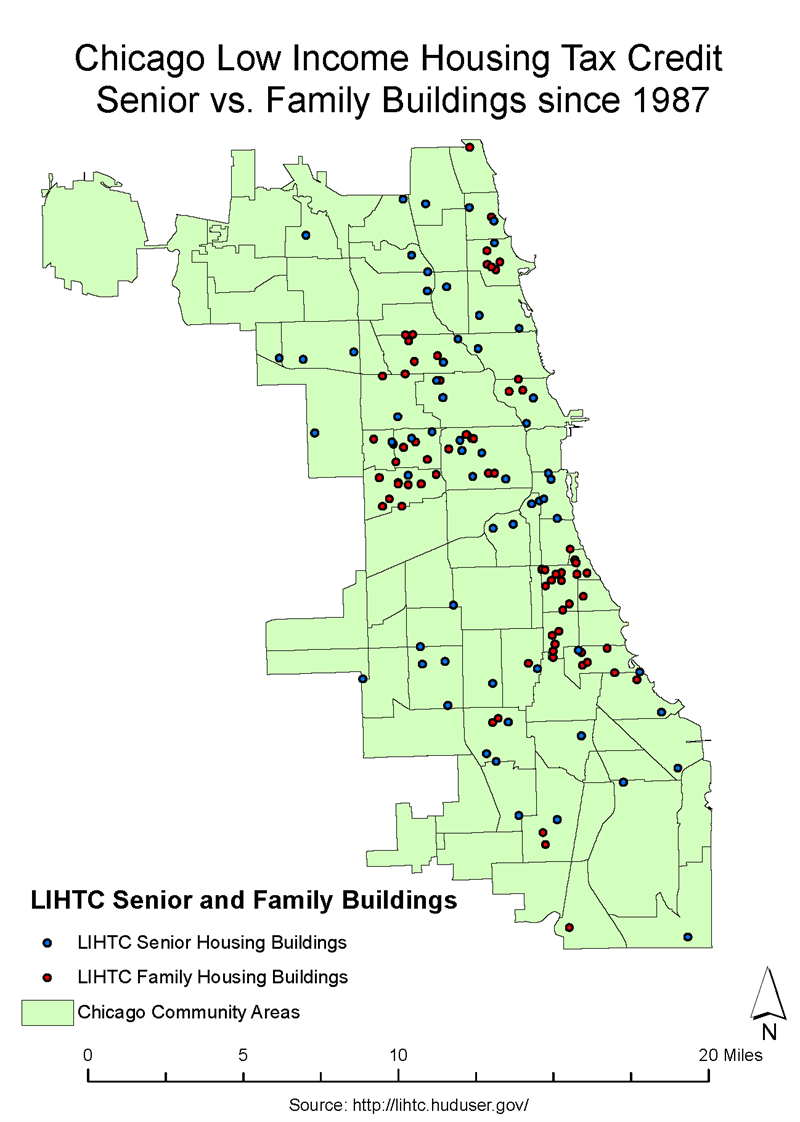

“Only 10 percent of the population of the city of Chicago are over 65, yet 39 percent of all affordable housing built or preserved over the last five years was for seniors. Senior housing was also the only kind of affordable rental development on the far southwest and northwest sides of the city.”

In another snapshot, this time for the third quarter of 2014, the Rehab Network found that more than half of approved affordable rental properties were for seniors only, and that year-to-date, just 25 percent of affordable rental units were for families.

Why might that be?

Most semesters, I guest lecture for a course at the University of Illinois at Chicago’s urban planning program. I always quote the Rehab Network’s statistics and ask students the same question: Why might this be?

Students usually speculate that we must have an increasing senior citizen population and that seniors are more likely to be low-income than the general population.

Ok, I say, and what else?

During this winter’s lecture, for the first time a student ventured a guess that maybe low-income seniors are less threatening than low-income families.

Bingo.

Let’s be clear what’s at play: ageism and racism. In this instance the typical conception of ageism as anti-elderly is quite the opposite. In this case, the older are preferenced over the younger, especially when the younger involves families. According to Allison Bethel, executive director at the John Marshall Law School Fair Housing Legal Clinic, "Family status discrimination happens all the time."

MPC Research Assistants Valerie Poulos and Matt Tyczinski

We typically think of housing discrimination against families occurring when a landlord refuses to rent to someone who has children (which is illegal under the federal Fair Housing Act). But what if the discrimination occurs earlier, blocking the housing from being built in the first place?

Furthermore, when that family includes a teenager—particularly a young person of color—issues of discrimination ratchet up still further. Why? Because nothing and no one elicits fear like a black or brown teenage male.

Ephebiphobia

There is actually a term for this: Ephebiphobia, the fear or loathing of teenagers. Ephebiphobia coupled with racism is a tough nut to crack for any alderman or municipal leader trying to meet affordability goals and keep his or her job.

A recent example is illustrative: In 2010 a North Shore community put out a call for affordable housing for families. The Lake County Residential Development Corporation applied and was chosen to implement their vision for 18 units of affordable rental housing in the community.

The mayor who had initiated and supported the project, however, subsequently left office. During the various approval processes for funding and zoning changes that ensued, community residents raised strenuous objections to the 18 affordable units for families. Eventually, the town leadership came back to Lake County Residential Development Corporation and requested that they change their plan to affordable senior housing instead.

Having already received financing for family units, the development corporation had to walk away from the deal, and the community—which desperately needed affordable housing—got none.

We already have solutions.

What if we actually had the tools to enforce the laws we have, such as the statewide Affordable Housing Planning and Appeals Act? Passed in 2004, the law requires towns with less than 10 percent affordable housing to create a plan to rectify that, and provides a process for affordable housing developers whose projects are rejected in those towns to appeal. But in the 12 years since its passage, a total of zero developers have appealed under the law.

Why? Its enforcement measures were stripped in order to get it passed. The spokesperson for the Illinois Housing Development Authority, the entity tasked with overseeing the law, summed up its helplessness this way: “We do feel that our hands are very much tied. We are not a regulatory body. We don’t have a stick.”

On a national level, the Fair Housing Act of 1968 was intended to change this bending to whims of local prejudice. As this ProPublica article covers in painful detail, however, president after president since then has failed to proactively combat segregation.

As I’ve written before, last summer’s announcement by the U.S. Dept. of Housing and Urban Development of its final rule on Affirmatively Furthering Fair Housing provides some hope that municipalities will be called upon to proactively promote fair housing. Under the new rule, communities cannot perpetuate segregation.

It can’t come too soon. As sociologist Matthew Desmond notes in his new book, Evicted, three-quarters of families who qualify for housing assistance don’t get it because we haven’t sufficiently funded affordable housing. We exacerbate that when we take the politically easier route of under-providing for families.

MPC Research Assistant Valerie Poulos contributed data to this post.