Flickr user Henk Sijgers (CC)

In this series, the Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) will explore where Chicago’s middle class lives, along with mapping the middle class experience by race and how it’s changed over time for both the city and the region.

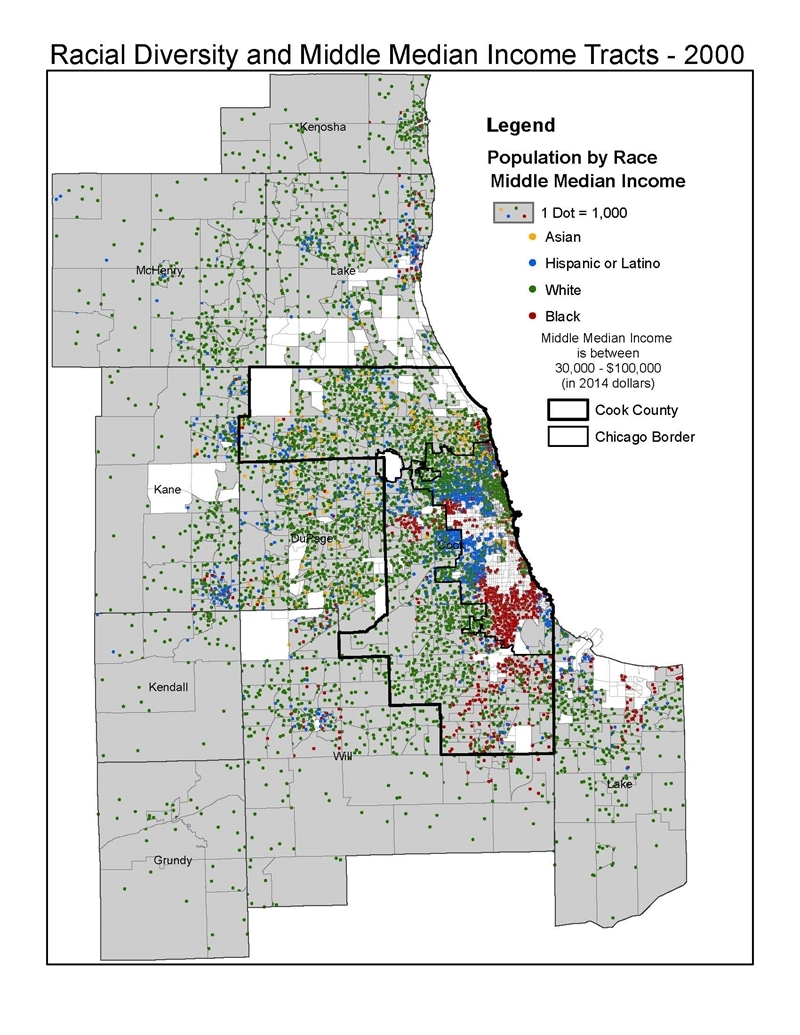

In previous posts, I examined how Chicago’s middle class census tracts break down spatially and by race, and then turned to the region’s layout by the same. Here’s how this shift in middle class population across the metro breaks down spatially, starting with the year 2000:

Benton Dosky

First of all, outside of Cook and DuPage counties, middle class population density drops off dramatically (as does overall population). While there are pockets of Latinos in middle class census tracts throughout the region, from Waukegan to Aurora to Joliet, there is little African American population in middle class census tracts outside of Cook County.

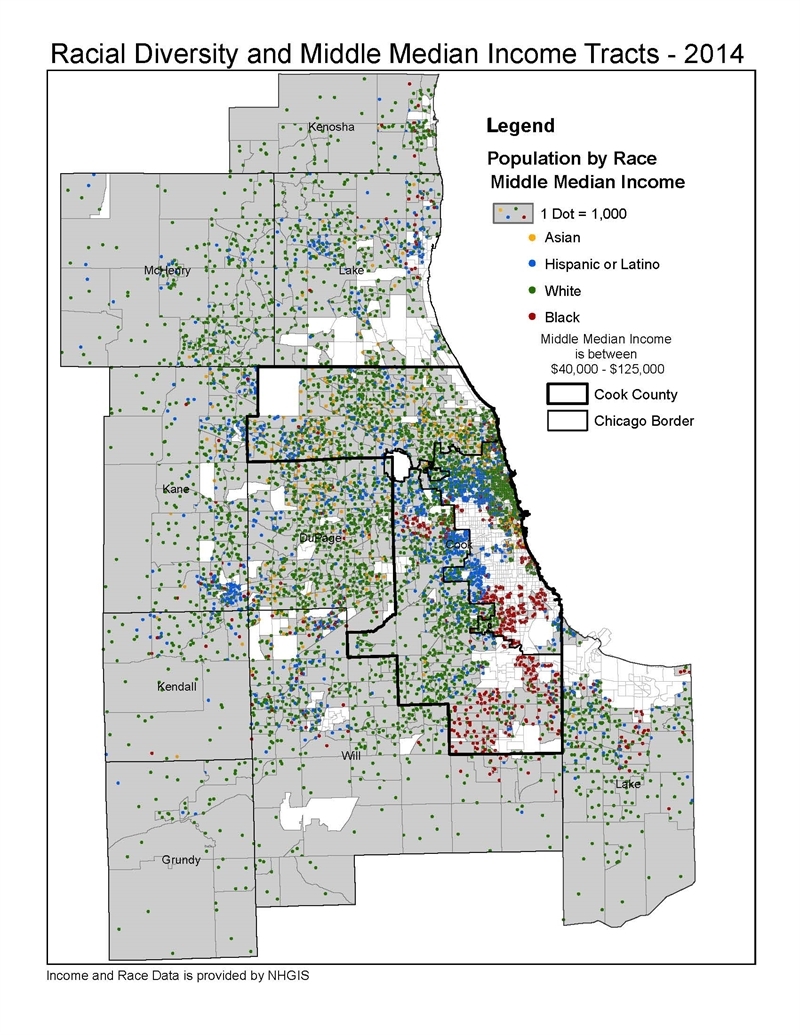

When we skip ahead to 2014, we see that Latinos in middle class tracts have become not only more numerous—from 17 percent to 20—but also more integrated throughout much of the region. African Americans, in contrast, decreased from 13 percent to 10, and by and large remained in clusters within Cook County.

Benton Dosky

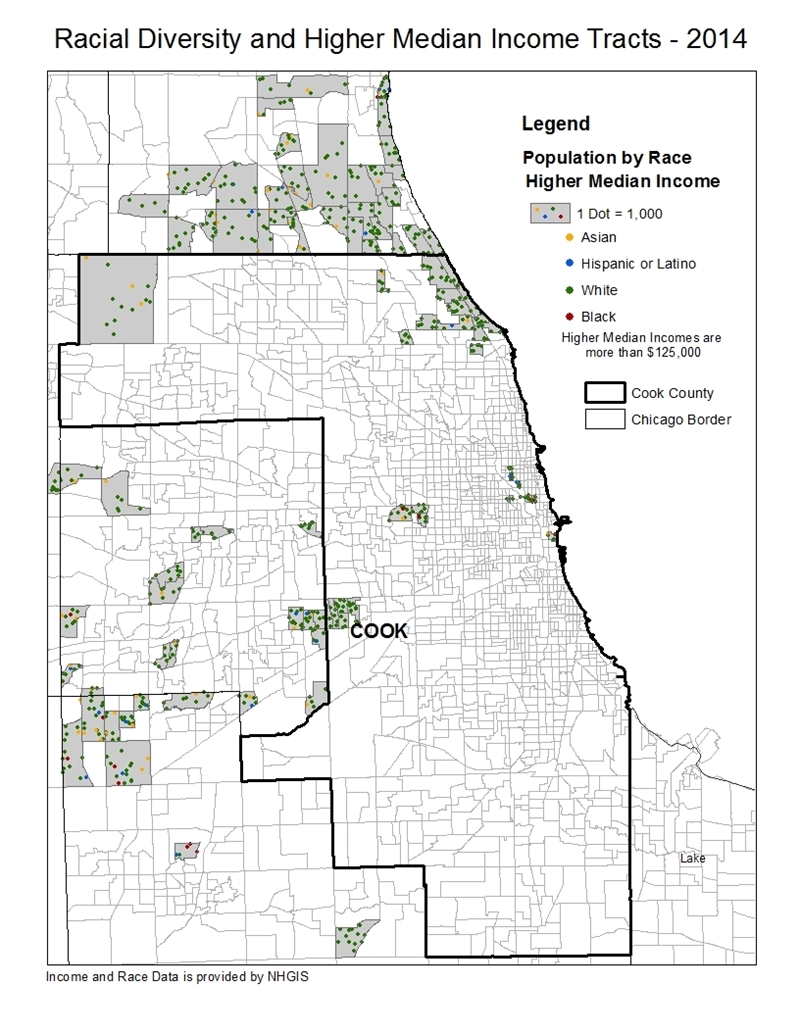

All racial groups except for whites increased their presence in upper income tracts from 2000 to 2014.

When compared to upper class census tracts—those where incomes are above $125,000—it’s clear that 1) there aren’t very many, and 2) Latinos in middle class tracts live much closer to wealth than African Americans in middle class tracts. Interestingly, all racial groups except for whites increased their presence in upper income tracts from 2000 to 2014. Asians went up 60 percent from 5 to 8, Latinos increased 100 percent from 2 to 4, and African Americans increased from 2 to 3 percent. Whites, instead, dropped 8 percent from 90 to 83 percent, by far still the dominant group in these tracts.

Benton Dosky

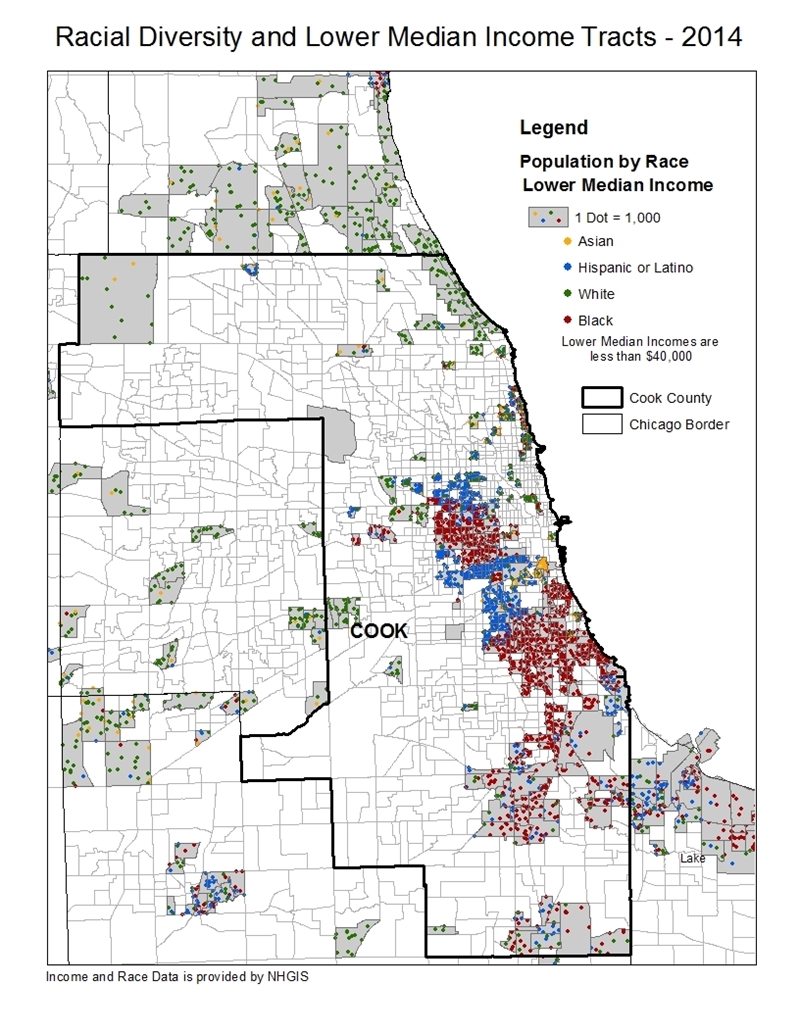

Finally, census tracts with low-income medians—below $40,000—show a distinct pattern: small clusters in the more densely populated areas outside of Cook County in Waukegan, Aurora, Joliet and northwest Indiana, and then densely concentrated within the City of Chicago and south suburban Cook County.

Benton Dosky

A few observations:

- From 2000 to 2014, all groups gained population in low-income census tracts except for African Americans. Asians increased 50 percent from 2 to 3 percent, Latinos jumped 60 percent from 20 to 32 percent, and whites increased 67 percent from 9 to 15 percent. African Americans, in contrast, dropped 28 percent from 68 in 2000 to 49 percent in 2014. To what do we owe this decrease? Perhaps it has to do with African American population loss overall?

- White population in the region’s middle- and upper-income census tracts dropped by 3 and 8 percent, respectively, from 2000 to 2014. Despite this, my colleague Alden Loury recently found that majority black and Latino suburbs were more likely to lose population than mixed or majority white suburbs.

- Alden also discovered significant racial changes to the suburban landscape between 2000 and 2010, during which “six majority white suburbs flipped to majority Latino, including west suburban Berwyn and northwest suburban Carpentersville. Three more majority white suburbs became majority black during that decade, all of them in the south suburbs, including Park Forest and Sauk Village.”

- In fact, in 2000, “there were 21 majority black and three majority Latino Illinois municipalities in the Chicago region, according to his analysis of Census data. By 2010, there were 26 majority black and 13 majority Latino cities, towns and villages.”

What’s the upshot? Patterns I covered in my city-only analysis hold true for the region as well: People of color living in middle class census tracts are much more likely to be surrounded by low-income census tracts than is the white middle class. In the case of suburban Latinos, though, with a relatively strong presence in the north, northwest, and west suburbs, this trend is much less stark than for city-dwelling Latinos.

The city of Chicago may get the bulk of the headlines, but it isn’t the only municipality in our region dealing with segregation. As my colleague Alden’s closer look at suburban municipalities suggests, the region’s long-standing segregation patterns are holding firm, while communities of color are struggling the most with population loss. As we study the cost of segregation, we find indications that the further apart we live by class and race, the harder it is for our economy to thrive. Those who live far from the city or far from its most struggling neighborhoods may not think this affects them, but the more we learn, the more indications we find that this is a comfortable fallacy.

If all are affected, how should we all respond? We look forward to sharing the first of our findings this fall.

To learn more about Chicago's middle class, read the other posts in the series.