Flickr user John Greenfield (cc)

In the suburbs, transit use barely makes a mark.

Published monthly, MPC’s Talking Transit, supported by Bombardier, provides updates about transit-related activities around the world. Read In the Loop for the latest transportation headlines.

Did you know?

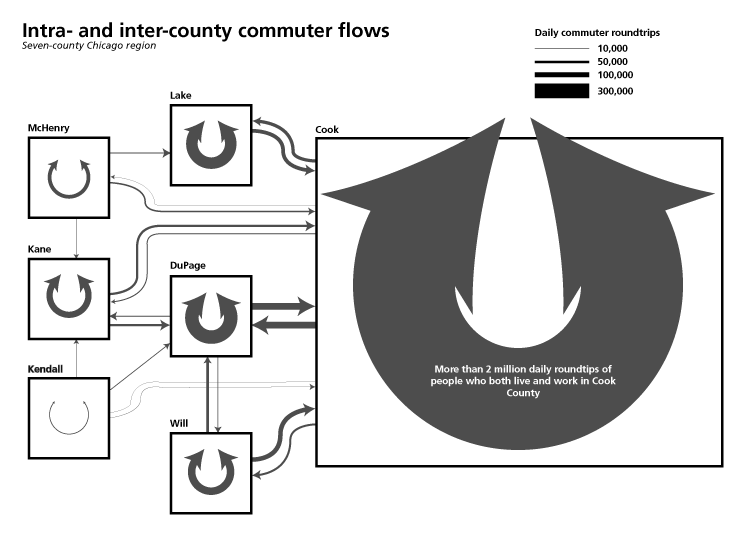

Of the almost 4 million people both working and commuting in the seven-county Illinois portion of the Chicago region, more than half both live and work in Cook County, according to an analysis of U.S. Census Bureau 2009-2013 data. That’s reflective not only of the dominance of the city of Chicago and its jobs-heavy Loop, but also of the fact that, in general, most people work relatively near to where they live; in fact, 76 percent of the region’s employees both live and work in the same county.

But the experience of commuters in different parts of the region differ considerably, and in this article, I’ll delve into the travel patterns of commuters in the metropolitan area, with a specific focus on people taking advantage of public transportation. It is worth emphasizing that the data this article relies upon solely provide information about work trips because that is the data available from the U.S. Census. In other words, the data are heavily weighted toward understanding how people move around when traveling to work, and do not reflect other trips. Keep that in mind when considering this post.

Commuter flows around the region

As noted above and illustrated in the following chart, commuter travel in the Chicago region is dominated by travel within Cook County. Much of this travel is within the city of Chicago, or between Cook County suburbs and Chicago or from Chicago to Cook County suburbs.

That said, there are significant flows of people between counties as well. Roughly 135,000 people travel from homes in Cook County to jobs in DuPage County, and 137,000 people do the inverse. 64,000 Cook County residents travel to jobs in Lake County, and 78,000 people do the inverse.

Chicago is a world apart from the rest of the region when it comes to using transit

Commuter flows as a whole mask the more complex fact that people travel around the region in different ways. What’s apparent from evaluating transportation mode share data provided by the Census Transportation Planning Package and the U.S. Census American Community survey, which monitors how people in given areas travel to work, is that the city of Chicago is in a league of its own compared to the rest of the region.

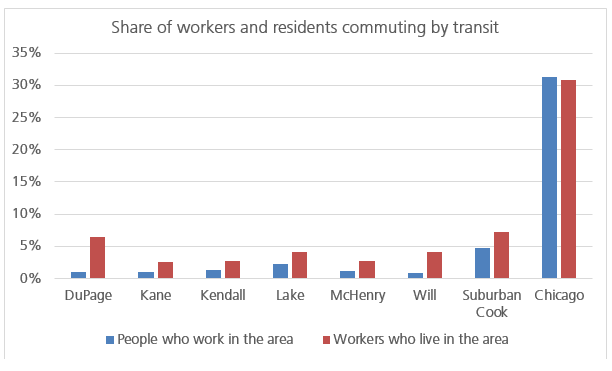

More than 30 percent of people who live in the city of Chicago and more than 30 percent of those who work there (remember, many people who work in Chicago do not live in Chicago, and vice versa) take transit to work. In suburban Cook County, only 7 percent of those who live there take transit, and only 5 percent of those who work there do.

In the outer suburban counties, as the following graph shows, transit use is even sparser, with the share of people who work in those counties and use transit at less than 3 percent.

The share of people who take transit to work who live in suburban areas is uniformly higher than the share of those who work in those areas. There’s a good explanation for that phenomenon: people who work in Cook County, wherever they live, are more likely to take transit to work than people who work elsewhere.

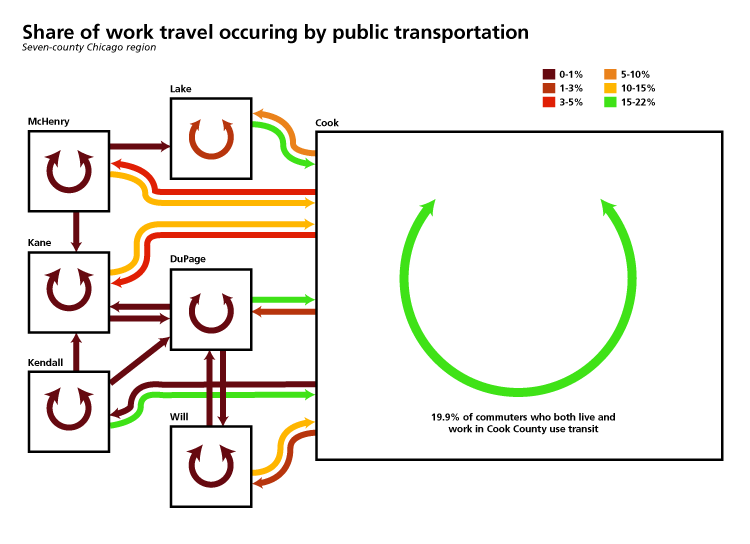

Take DuPage County as an example. As the following chart shows, people who live in DuPage County but work in Cook County are much more likely to take transit to work (19.8 percent of them) versus those who work in DuPage County (0.4 percent—you’re reading that right, less than one percent) or any of the other collar counties (between 0 and 1.3 percent).

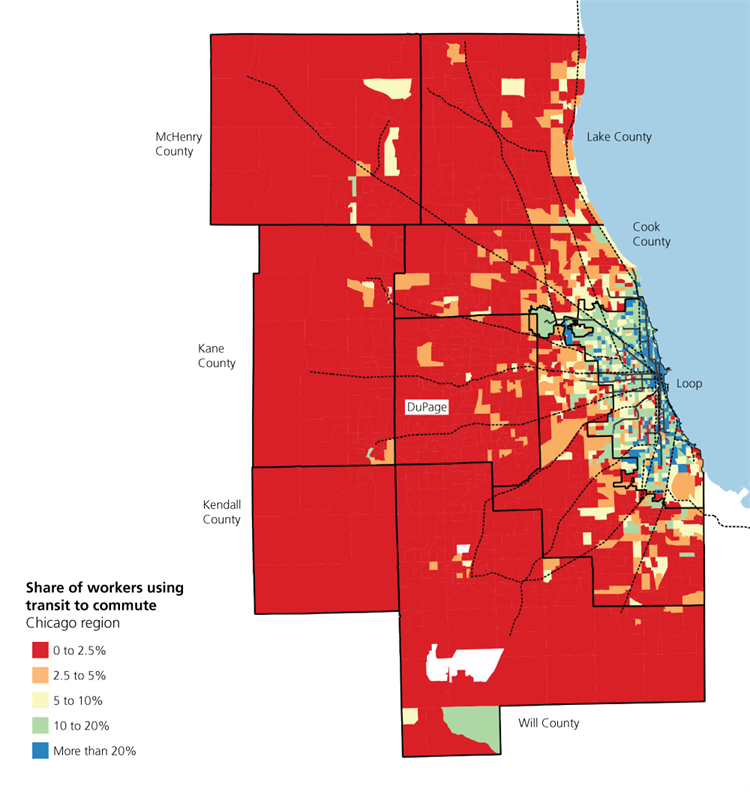

Indeed, while the transit share or work trips into Cook County is 10 percent or more from all counties in the region, the transit share for all other trips involving work in the other suburban counties is 6.1 percent or less. For most commuting trips in the suburbs, less than 1 percent of trips are conducted by transit (shown in the darkest red on the following chart).

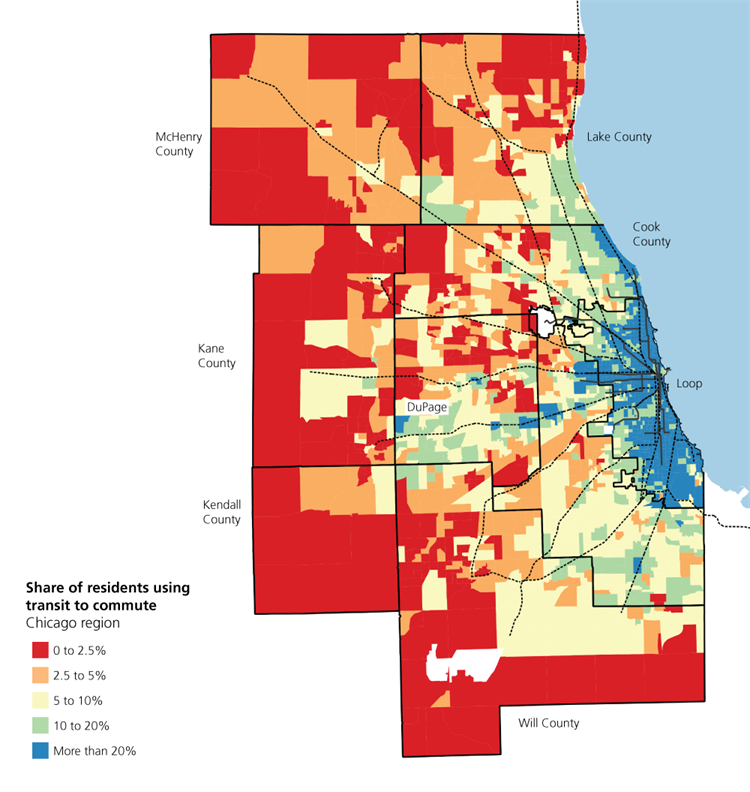

When examining these trends on the Census Tract level (a neighborhood-scale level of analysis), these patterns become clearer.

As the following map shows, transit use by residents in the Chicago region is heavily concentrated in the city of Chicago, but areas of significant use of train and bus services to get to work extend north along the lakefront in suburban Cook and Lake Counties, south into southern Cook County, and west into western Cook County and DuPage County. In general, the further the community from the Chicago Loop, the less likely its residents are to take transit to work.

These trends are magnified when examining data about where people work. Examining the following map shows that outside of Cook County, fewer than 2.5 percent of people who work almost anywhere in the region take transit to work. By job location, transit use is incredibly concentrated in Chicago, and even more so in the Loop.

Service matters

To understand why people in certain areas of the region are more or less likely to take transit, it’s worth emphasizing that transit use is often a byproduct of a community’s environment. Neighborhoods with the highest density and a mix of uses are more likely to attract transit use than sprawling, single-use ones. And the reality is that in the Chicago region, dense, mixed-use neighborhoods are mostly in the city of Chicago.

It is also true that the region’s transit system—particularly its rail network—is heavily oriented toward providing service to the Loop. Metra commuter rail and CTA L lines radiate outward from stations downtown, which provides excellent accessibility but doesn’t provide great service to jobs elsewhere. Because jobs in much of the rest of the region are in office parks and manufacturing facilities designed around providing good access by automobile, providing good transit offerings there is difficult for operators and hard to use for workers.

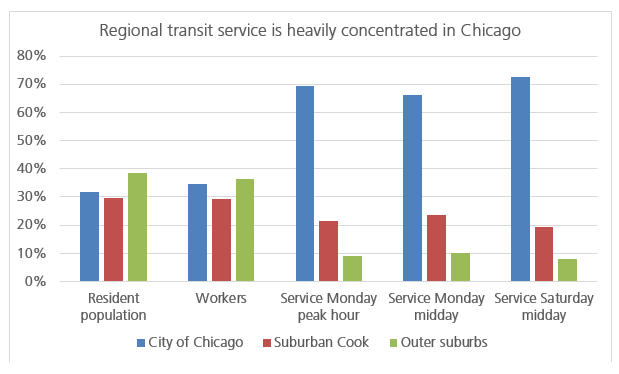

But when compiling overall bus and rail service data, a broader trend becomes apparent. While the city of Chicago, suburban Cook County and the outer suburbs each account for about a third of the region’s population and workers, transit service is extraordinarily oriented toward Chicago.

As the following chart demonstrates, the city of Chicago gets 70 percent of the region’s transit service at peak hours and between 66 and 73 percent of it off peak. On the other hand, the outer suburbs get only about 10 percent of the region’s transit service. With trends like these, it is hard to be surprised by the rather low levels of transit use outside of the central city. Much of the difference is a consequence of the presence of the Chicago Transit Authority in the city, which has higher levels of service standards than are available in much of the suburbs. It is worth noting that Cook County residents pay a higher sales tax than their suburban counterparts to fund better transit.

Service was calculated by examining regional transit schedules (referred to as GTFS) and running them through the BetterBusBuffers plugin created by Melinda Morang. This plugin calculates the number of times buses or trains are scheduled to stop at each point in the regional transit network. Service, then, is defined as the share of buses or trains stopping per period (either 8 to 9 a.m. or 12 to 1 p.m.) in each of the areas (Chicago, suburban Cook County and the rest of the regions).

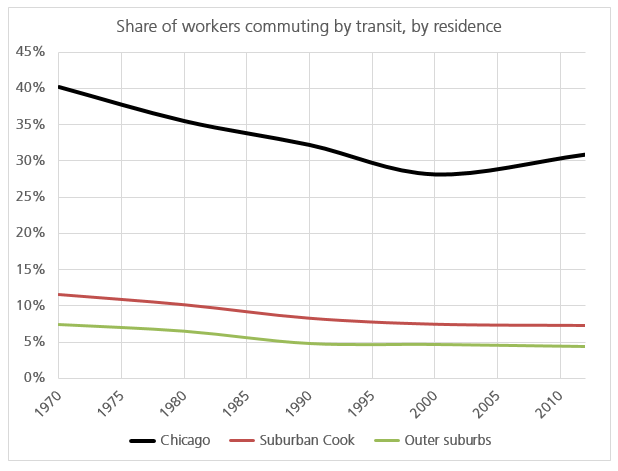

The region’s transit use has followed a downward trend—at least until recently in Chicago

The Chicago region will have to expand investment in its transit services if we want more people to ride buses and trains. As the following chart demonstrates, the share of residents commuting to work by transit has declined rather continuously in the Chicago region suburbs since the 1970s. Only in the city of Chicago itself has there been an uptick since 2000.

Investing in better suburban transit is in many ways more difficult and expensive than improving transit in urban areas. Buses and trains operating in the suburbs are likely to attract fewer riders per dollar spent because of those areas’ lower density of population and jobs. But given the Chicago region’s reality of virtually no transit use outside of the city, it’s time to rethink how to make better service in those areas possible.