Detroit's Sicilian enclave of Cagalupo, 1946. My father is the little boy on the far left.

The Metropolitan Planning Council, in partnership with the Urban Institute, is conducting a study on what segregation costs the Chicago region. We’ve started with a question: In Chicago, known for its stark residential divides by income and race, is our segregated status quo cost neutral? And if not, what can we do about it?

I should note that I am not, nor is anyone involved with this study, arguing that integration is a panacea for all problems. Nor are we under the illusion that we can snap our fingers and undo a century of discriminatory policies that began in earnest 100 years ago with the start of the Great Migration. Rather, our belief is that the policies and prejudices that created and maintained segregation may have changed over time but their existence and impact persists, and that people having real choices when it comes to building the healthiest version of their family possible is a worthy goal. Over the next year, we will be working on both understanding the cost of segregation to Chicagoans and on advancing policies that create more options for more people.

In my many conversations with people about this work, I’ve heard a fair amount of pushback—from people of all races—on the notion that integration is worth pursuing. So much so that I’d like to unpack the most common arguments I’ve heard, and offer a few thoughts in response.

"Ethnic enclaves are incredible places. Why should we want to break them up?"

Ethnic enclaves can indeed be incredible places, as they have helped innumerable new immigrants acclimate to American life, preserved and celebrated cultures, and provided the backdrop for locally owned economic activity. They are also not what we’re talking about when we refer to segregation.

My dad grew up in a Sicilian enclave called Cagalupo on the east side of Detroit. We went back to the area last year and walked the route he used to take from the vacant lot that had been his family home to his elementary school and parish. As we walked, my dad pointed out all the (now gone) markers that had defined the close-knit nature of his childhood: "That was my Uncle Leo's house, we used to sit on his porch and listen to Tigers games;" "That was the corner store where my mom would send us to pick up a slab of hard cheese;" and "My grandmother lived on this block, and I'd stop there after school for a slice of fresh baked bread."

The benefits of this cultural and geographic closeness are abundant. But let's be clear: Had my dad's family wanted to move across town to be closer to the Ford plant where my grandfather worked, they could have. And if moving there meant relocating to a predominantly Polish or Irish neighborhood, they could have.

Why? Because white ethnics (immigrants and their descendants from Southern, Central and Eastern Europe), while facing discrimination in early generations, were ultimately considered white and could integrate among themselves and into the mainstream much more easily than immigrants and migrants with darker skin.

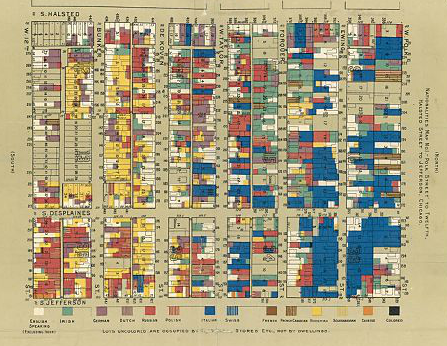

Consider this map of nationalities created by the Hull House Settlement around the turn of the last century:

Encyclopedia of Chicago

The key reads from left to right: English speaking (excluding Irish), Irish, German, Dutch, Russian, Polish, Italian, Swiss, French, French Canadian, Bohemian, Scandinavian, Chinese, Colored.

While there were certainly blocks that were more heavily Italian or Russian or Bohemian, there is a level of mixing that is unheard of in comparison to the stark lines drawn around Chicago’s Black Belt. When African Americans attempted to breach these lines by moving into white areas (after clearing the hurdles set for them by redlining from the Federal Housing Association and local realtors’ groups), they were met with riots and violence.

While laws are different today, these trends continue. A recent Harvard study found that Chicago neighborhoods that are more than 40 percent African-American don’t gentrify. My own look at Chicago middle class census tracts found that in contrast to areas with high levels of the white middle class, African Americans and, to a lesser extent, Latinos in middle class census tracts are largely surrounded by tracts with lower median incomes. African Americans make up 75 percent of the population in these lower median income tracts, compared to 16 percent for Latinos, 5 percent for whites and 3 percent for Asians. Nationally, just 11 percent of neighborhoods with socioeconomic gains from 1990-2009 were predominantly African American. In sum, the ethnic enclave experience is highly race-dependent.

It is still true that ethnic enclaves can be incredible places of strength and vibrancy. And it is also still true that they are not the same thing as areas formed by state-sponsored segregation that disproportionately negatively impact African Americans. The former are largely places that people opt into for the benefits they perceive them to bring; the latter are places in which the ability to opt out is highly constrained.

"People just want to live near people like them; it's natural."

A study by the University of Illinois at Chicago's Maria Krysan, et al. delved into this claim, and their findings contradict the notion that minorities voluntarily "self-segregate." After surveying a range of households in Cook County over a one-year period, Krysan found that White, Black and Latino residents all reported a preference for living in diverse neighborhoods. However, while Whites searched in areas that were much whiter than their stated preference, African Americans and Latinos actually did search in areas that matched their preferred level of diversity.

Findings from Krysan's 2015 study, Diverse Neighborhoods: The (mis)Match between Attitudes and Action

"Where things fall apart for African Americans is in the step from searching to moving--despite searching in diverse neighborhoods, blacks end up living in neighborhoods that are on average 66% black (see Column 3 in the figure). A similar, though less extreme pattern occurs for Latinos: They search in diverse neighborhoods where Latinos are, on average, just 32% of the residents...but they end up living in just over majority Latino (51%) neighborhoods."

Krysan notes that a reason for this disconnect between African Americans’ and Latinos' stated preferences and search areas compared to where they end up may be due to "hostility or discrimination when searching in these neighborhoods, thus creating barriers that impede them from translating their attitudes into action."

The study does not yield conclusive answers, but it raises enough questions to make me more than a little skeptical of the notion that where people live is based solely on what they want. Consider the case of Housing Choice Voucher holders (formerly known as Section 8), many of whom have chosen to remain in areas that are the same or similar to those they inhabited with public housing because they prefer an area with which they are familiar, where they have family ties, perhaps help with childcare and other supports. Many others, though, have tried mightily to live elsewhere and, after hitting roadblock after roadblock, have given up. This is not living where they choose to live. This is living as well as they can within the confines of structural racism.

"The goal of integration suggests that people of color are somehow insufficient on their own, that they need white people to be whole."

It does suggest that, and that is highly problematic. As Northwestern sociologist Mary Pattillo argues, proximity to whiteness is not a solution unless we start from the premise that the problem is blackness.

So given that blackness isn’t a problem, and whiteness isn’t somehow magical, why are we talking about this?

For more than a decade, I lived just a block north of the border between North and South Lawndale, neighborhoods that are predominantly African-American and Mexican-American, respectively. In my years living and working there I never heard from my neighbors or co-workers that they wished they could live near more white people.

What I have and do hear them say is they wish they could send their kids outside without fear of violence. They wish their neighborhood school was better resourced. They wish they could walk to a quality grocery store.

Achieving those things shouldn’t have to equate to living around white people, but because of how closely income is tied to race, and how much racism still exists in retail and housing markets, in this country it usually still does. As Natalie Moore argues in her book The South Side, segregation is crippling not because whiteness is superior, but because “unofficial ‘separate but equal’ isn’t working out too well for us.” Or as New York University sociologist Patrick Sharkey puts it:

Residential segregation provides a mechanism for the reproduction of racial inequality. Living in predominantly black neighborhoods affects the life chances of black Americans not because of any character deficiencies of black people, not because of the absence of contact with whites, but because black neighborhoods have been the object of sustained disinvestment and punitive social policy since the emergence of racially segregated urban communities in the early part of the 20th Century.

In other words, as Mary Pattillo acknowledges in Natalie Moore’s book, segregation is a problem only because it allows for the unequal distribution of resources.

I see this as being about the intersection of race and racism, and the need to not comingle the terms.

There is nothing inherent about race itself...There is, however, everything that is pervasive and pernicious about racism.

There is of course nothing inherent about race itself, no intrinsic magic or deficits with which races are somehow imbued. There is, however, everything that is pervasive and pernicious about racism. And as long as there are wage, wealth, health, incarceration and education differentials by race, as well as deep racism in housing and retail markets, then integration needs to be part of the conversation.

These are some of the questions we’ve been grappling with at MPC as we work with the Urban Institute to gauge the economic impact of segregation on Chicago. What we do about these impacts is undoubtedly complicated. Ultimately, Pattillo argues to Moore that dramatically re-investing in disinvested, predominantly African-American neighborhoods should be the first goal, and that is an integration strategy unto itself. Solutions certainly need to address unequal distribution of resources regardless of integration, as well as creating more choices for more people across the Chicago region.