Flickr user Cheryl DeWolfe

Former neurosurgeon and presidential candidate Ben Carson was recently confirmed to run the Department of Housing and Urban Development. While he has no background in this line of work, he expressed a few opinions in a 2015 Washington Times op-ed, in which he called active efforts at integration and fair housing a “social engineering scheme.”

He’s not the only one who’s adopted this line of thinking. The Chancellor of New York City Schools, Carmen Fariña, has said that diverse schools are good and all, but they should just happen organically. At a 2016 town hall meeting, Fariña told parents “I want to see diversity in schools organically. I don’t want to see mandates.”

As someone who’s worked for decades on issues of equitable investment, affordable housing, and community development, I hear these kinds of statements a lot: that diverse neighborhoods and schools should just happen. Organically.

The Whole Foods produce department has nothing on real life.

If you were a person of color, next to nothing happened organically in terms of where you could live or where you could go to school, and those patterns persist today.

2016 was the 100th anniversary year of the start of the Great Migration, so it’s a good moment for reflection. And the thing is, when you look back over the past 100 years, if you were a person of color next to nothing happened organically in terms of where you could live or where you could go to school, and those patterns persist today.

Those who would argue that efforts at integration are social engineering seem to forget that where people of color live has never not been engineered. Nikole Hannah-Jones reminds us that

“98 percent of the loans the FHA insured between 1934 and 1962 went to white borrowers…Banks often refused to approve loans for black soldiers attempting to use the GI Bill to buy homes. The Veterans Administration and the FHA officially supported racial covenants banning African Americans in new suburban developments until 1950.”

Beryl Satter's book Family Properties and Ta-Nehisi Coates’ searing article, The Case for Reparations, cover in painful detail the exploitation and financial ruin that met would-be African-American homeowners who were forced to buy their homes on contract because they could not get the protections that come with a regulated conventional loan.

For the past 100 years of substantial African American presence in Chicago, we haven’t let a single thing happen organically. Doing so now would actually be a huge departure from how it’s been done.

While many of the laws cited above no longer exist, sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva argues in Racism without Racists that “residential segregation, which is almost as high today as it was in the past, is no longer accomplished through overtly discriminatory practices.” A current example, as I’ve argued before, is the proliferation of public housing provision through Housing Choice Vouchers, the economics of which perpetuate present-day segregation regardless of the private prejudice – or lack thereof - of landlords.

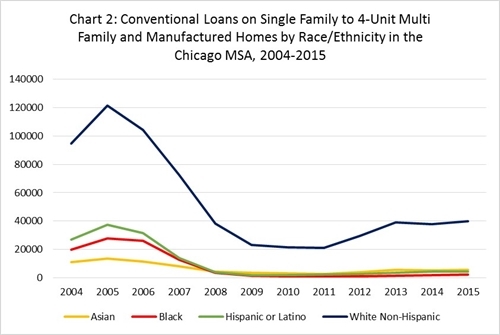

Another example is that fifty years after the creation of the Contract Buyers League to fight Chicago’s unscrupulous unregulated lending, conventional home loans are still this bifurcated by race, according to the University of Illinois at Chicago’s Great Cities Institute:

Matt Wilson, UIC Great Cities Institute

So let’s acknowledge that for the past 100 years of substantial African American presence in Chicago, we haven’t let a single thing happen organically. Doing so now would actually be a huge departure from how it’s been done.

But we’ve never been particularly good at acknowledgement in America. I was fascinated by a piece I read recently by a German now living in New York, who says that as a country they have worked hard to understand how something as horrific as the Holocaust could have been birthed among them. They even have a word for this process of understanding: Vergangenheitsbewaltigung, meaning “the process of coming to terms with your past.”

My third-grade son recently brought home a Black History Month fact sheet which noted how African Americans were subjected to Jim Crow laws in the South, with no mention of the plethora of discriminatory laws north of the Mason-Dixon line. The handout reads: “After the Civil War, many southern

We have yet to fully acknowledge how deliberate and proactive we’ve been in establishing and maintaining our segregation.

states still treated black people badly. They made up laws that kept black people separate from white people.” With a dose of vergangenheitsbewaltigung, maybe we should be willing to teach our children that the entire country still treated African Americans "badly," the laws just looked different depending on where you lived. I wonder if we have such a hard time with the need to be deliberate and proactive to achieve integration because we have yet to fully acknowledge how deliberate and proactive we’ve been in establishing and maintaining our segregation.

It only makes sense that taking steps to deconstruct segregation must be just as deliberate as those taken to create it, and we don’t need to be afraid of that. Consider the southwest side community of Beverly. Today, Beverly is 62 percent white and 34 percent African American, while nearby communities reflect more extreme racial poles: neighboring Mount Greenwood is 91 percent white and Auburn Gresham is 98 percent African American. Beverly didn’t become integrated organically.

I recently listened to an audiotape of a speech that lifelong Beverly resident Pat Stanton gave in 1971, at the height of white flight in communities to the east of them. In his talk to an all-white audience at Christ the King parish, Mr. Stanton methodically walks through the steps he urges them to take to become an integrated community rather than giving in to panic peddling and leaving en masse as other residents of South Side neighborhoods had done before them. Moving through his felt-tip marker flipchart, he lays out his argument: “There are thousands of blacks who want homes, can afford homes, and deserve to live where they can afford to…they should be able to look everywhere. They are welcome, and they should be throughout (the community)…The whole point is coordination… Change is inevitable. Non-controlled change doesn’t have to be…We need a coordinated program…Through long-range planning, we can manage this change.”

And ultimately, the community did adopt methodical steps: they worked with existing homeowners to sign non-solicitation pledges so that unscrupulous realtors could not panic peddle, they identified realtors who committed to show would-be African American homeowners options throughout the entire community rather than in segregated pockets, and, crucially, they gave a mandate to an umbrella community organization to carry out their mission to “integrate, not re-segregate.” It took work, in other words; Beverly’s integration didn’t just happen.

Is Beverly nirvana today? No. Nowhere is. But is it more diverse and integrated than it likely ever would have been had 1970s-era residents just waited to see what would happen organically? Undoubtedly.

In September, London mayor Sadiq Khan was in town and I went to hear him speak. In the course of his remarks he introduced his new Deputy Mayor for Social Inclusion, a position he created because, he explained, diversity is not the same as integration and a laissez-faire approach to integration doesn’t work.

What might it mean to have such a position in Chicago, one that acknowledged that decreasing our segregation won’t happen quickly enough on its own? It could mean that Chicago Public Schools would embrace the opportunity to merge majority-white Ogden and majority-African American Jenner schools, as both school principals have been urging for years. It could mean pushing for affordable housing to be built in substantial numbers in all 50 wards, not only where elected officials are sympathetic or land is cheap. Across the region, it could mean Housing Choice Vouchers reach rent levels that allow recipients real choice in the places where they live and raise their families. It could mean municipalities engaging in affirmative marketing for middle class households, as the Oak Park Regional Housing Center has successfully modeled for years.

With an amazing team of advisors and working groups, MPC is exploring all of these options and more through our study on what segregation costs the Chicago region. As part of this work, we will be recommending policies that affirmatively further integration in our region.

We have drawn hard and fast lines in the sand of our city and region, and without a real attempt at vergangenheitsbewaltigung, lessening our segregation will continue to be harder than it should be. If we value diversity we have to make deliberate decisions to prioritize it. It’s disingenuous to cry “social engineering” foul today. Segregation was caused by social engineering. We will need to be just as deliberate to undo it.