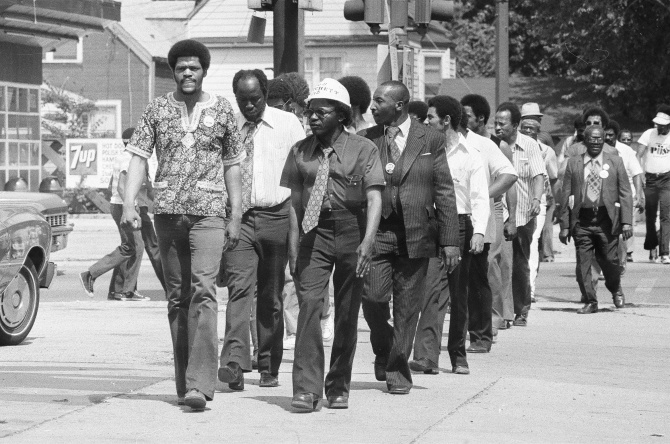

Sun Times Photo

Demonstrators march through Chicago's Marquette Park neighborhood in 1976 to protest racial segregation in housing.

The following op-ed was originally published in the Chicago Sun-Times.

If the Chicago region were less segregated, it could see $4.4 billion in additional income each year, a 30 percent lower homicide rate and 83,000 more bachelor degrees.

These are some of the findings of a study released last week by the Metropolitan Planning Council and our research partners at Urban Institute. It's the first study to quantify the economic impact that living so separately has on everyone. Our goal is straightforward: to prove that segregation has a cost for everyone in our region, and to do something about it.

It is important to clarify that we are not arguing that desegregation is a panacea for all problems. Nor do we believe we can snap our fingers and undo a century of discriminatory policies. Rather, the policies and prejudices that created and maintained segregation have changed over time but their existence and impact persists, even as people having real choices when it comes to where they live and raise a family is fundamental to a just and equitable society.

In our many conversations about this work, we’ve heard a fair amount of pushback — from people of all races — on the value of desegregation. So much so that we’d like to offer a few thoughts on why our region needs to fully invest in inclusion as one of many strategies to fight inequality.

To begin with: Ethnic enclaves are incredible places. They are not the same thing as segregated places.

We often get asked why we support breaking up ethnic enclaves. We emphatically don’t. Ethnic enclaves can be incredible places, helping innumerable immigrants acclimate to American life, preserving and celebrating cultures, and providing the backdrop for locally owned economic activity.

They are also not what we’re talking about when we refer to segregation.

Marisa’s dad, for example, grew up in a Sicilian enclave called Cagalupo on the east side of Detroit. It was a close-knit community where his grandparents, parents, aunts and uncles spoke Sicilian, raised their families, sent their kids to school, attended church and shopped for their daily needs. The benefits of such cultural and geographic closeness are abundant. But let's be clear: Had Marisa's father’s family wanted to move across town to a Polish or Irish neighborhood, they could have.

Unlike white ethnics, when African-Americans attempted to breach neighborhood lines by moving into white areas (after clearing the hurdles set for them by redlining from the Federal Housing Association and local realtors’ groups), they were met with riots and violence.

While laws are different today, these trends continue. Families like Alden’s — who grew up on Chicago’s South side in the 1970s and '80s — more recently experienced firsthand the strict unspoken boundary: white at that time on one side of Western Avenue near 79th Street, African-American on the other. And racism has continued to dictate a dramatically unequal experience depending on which side of the line one resides.

In sum, the ethnic enclave experience is highly race-dependent, and not the same thing as areas formed by state-sponsored segregation that disproportionately negatively impacts African-Americans. The former are primarily places that people opt into for the benefits they perceive them to bring; the latter are places in which the ability to opt out is highly constrained.

As long as racism persists, intentional desegregation needs to be part of the solution.

Alden grew up on Chicago’s South Side and today resides in Auburn Gresham. For more than a decade, Marisa lived in North Lawndale. In our years in these communities, we’ve never heard from neighbors that they wished they could live near more white people. What we have heard from them is a desire to send their kids outdoors without fear of violence. To have a well-resourced neighborhood school. To have a quality grocery store nearby.

Achieving those things shouldn’t have to equate to living around white people, but because income is tied to race, and racism is rampant in retail and housing markets, it remains the reality. At the heart of the matter, this is about the intersection of race and racism; we cannot comingle the terms.

Race is made up; Racism is all too real. As long as there are wage, wealth, health, incarceration and education differentials by race, as well as deep racism in housing and retail markets that results in stark inequities, then desegregation needs to be part of the conversation.

What we do about the impact of racism is undoubtedly complicated. What we know for sure: segregation is a pernicious outgrowth of racism, and one of many important ways to address its resulting inequities is through intentional desegregation.