Jack Castillo

Protesting trickle-down economics

By Amy Khare and Jessica Smith & Alden Loury

By Amy Khare and Jessica Smith & Alden Loury - April 6, 2017

Last week, the Metropolitan Planning Council’s Cost of Segregation report revealed how expensive it is for the Chicago region to live so separately by race and income, and the price tag is in the billions: $4.4 billion in lost income; $8 billion in lost regional GDP; $90 billion lost in total lifetime earnings.

Simply put, we cannot afford to be so segregated. That’s why in the next phase of our work, we are examining equitable economic development policies that seek to change the systems that perpetuate racial and economic segregation and injustice. In doing this work, we’ve critically examined the economic and political forces currently at play in our region, state and country.

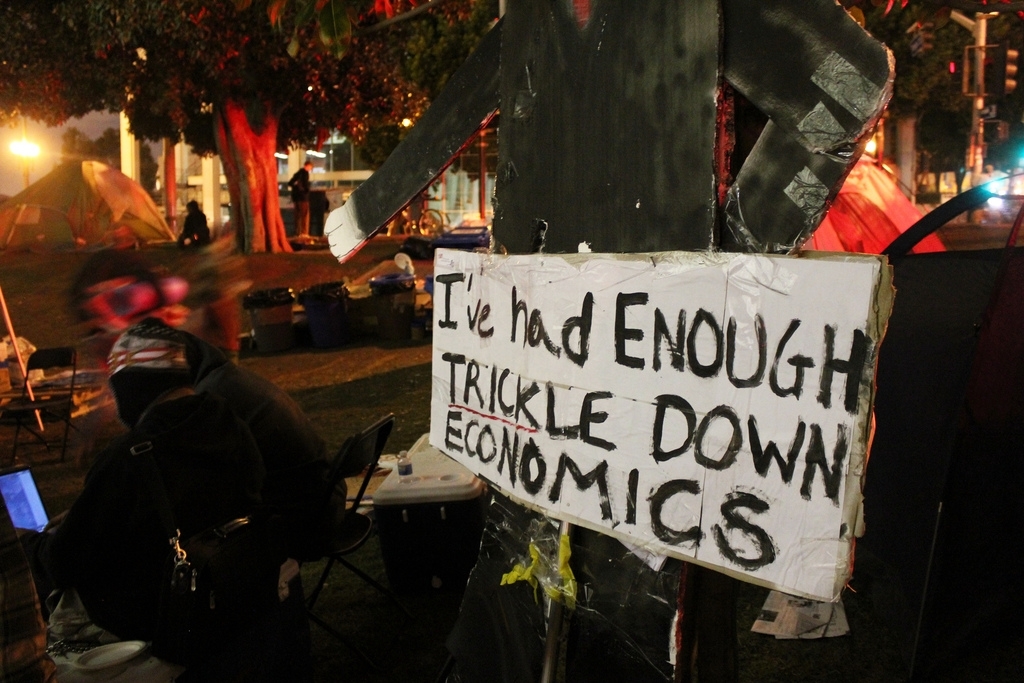

At the national level, it seems we are re-entering an era of trickle-down economic policy. Leadership is pushing income tax cuts for the top earners, deregulation of corporations and other powerful entities, and low minimum wages as solutions for business stagnation and unemployment. Locally, trickle-down approaches can be seen by Governor Rauner’s opposition to progressive tax hikes.

Chicago bears the mark of historical connection with trickle-down economics, which was promoted by economists, such as Milton Friedman, at the University of Chicago in the fifties. Today, those who believe in this economic theory would much rather it be called “supply-side” or “pro-business.”

In the decades since we’ve started to talk about trickle-down, we’ve accumulated a lot of evidence that wealth does not in fact trickle-down and improve economic mobility for everyone, including communities of color.

Research shows concentrated wealth negatively impacts metropolitan regions

Research shows that excessive concentrations of wealth and power at the top have negative consequences for nations across the globe and for metro areas, like Chicago.

According to recent research by the International Monetary Fund, such siloes of wealth hurt not only those at the bottom income levels but also the overall national economy:

“If the income share of the top 20 percent increases by 1 percentage point, GDP growth is actually 0.08 percentage point lower in the following five years, suggesting that the benefits do not trickle-down. In contrast, an increase in the income share of the bottom 20 percent (the poor) is associated with higher GDP growth.”

Along the same lines of inquiry, the non-partisan Congressional Research Service (CRS) issued a report in 2012 that analyzed the effects of tax rates from 1945 to 2010. The CRS concluded that top tax rates have no positive effect on economic growth, saving, investment, or productivity growth. They did, however, find that top tax rates increase income inequality.

We’ve seen this evidence play out in concrete terms on a federal level, during the Reagan administration—a period when taxes for the rich were cut. When the major tax cuts for the top began in the 1980s, that’s exactly when we saw national growth levels fall and income inequality rise. One result is that more people in the U.S. are working in lower-paying jobs, carrying more debt, and facing declining incomes compared to their parents’ generation, as explained by the Roosevelt Institute’s report Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy.

Segregation and increased inequality and injustice

So, what does excessive concentrations of wealth and power have to do with our latest report on the Cost of Segregation? We believe that these disparities drive economic and racial segregation, and therefore increase inequality and injustice.

Income inequality has been on the rise since the 1980s. The latest economic research shows that American workers in the bottom 50 percent have not experienced income growth in 35 years, while those in the top 1 percent earn 81 times more than the average worker. In Chicago, this has contributed to an increased neighborhood polarization. As the University of Illinois’ Voorhees Center report shows, there are growing concentrations of wealthy areas alongside growing numbers of poor neighborhoods.

This growing inequality in Chicago’s neighborhoods has the most detrimental consequences for communities of color because they are disproportionately represented on the middle- to lower-income spectrum. Communities of color have also experienced disparate negative impacts from tax and asset-building policies, such as mortgage interest deductions that reinforce generational wealth. And here in Chicago, government policies reinforced racial segregation and inequality in ways that produced wealth divides, still present in 2017 as demonstrated by the Corporation for Enterprise Development (CFED) in their recent report.

On the other hand, some of the most exciting research on economic growth has come from the perspective of equity. MPC’s Cost of Segregation report highlights that metropolitan areas with lower levels of segregation experience, for example, higher African American incomes. Regions with higher levels of inclusion generate more long-term economic growth, while areas with higher levels of segregation have slower economic growth and shorter periods of economic growth.[i]

Leveling the Playing Field in Chicago: Equity and Inclusion

At a neighborhood level, we are encouraged by the Pullman community that MPC honored for its coordinated efforts to attract well-paying jobs for local residents. It’s a symbol of the benefits of sustained investment in underserved communities.

At the regional level, we are encouraged by early efforts to ensure inclusive growth. Cook County President Toni Preckwinkle helped launch a set of Chicago Regional Growth Initiatives, tackling disinvested areas in the South Suburbs. This focus on equitable regional growth is important—our local economy can only grow sustainably when we involve all communities in the process. We are also exploring efforts by local and state governments to align resources in ways that enhance equity and social inclusion.

MPC and our partners have a vision for an inclusive metropolis. Chicago’s diverse constituencies share a commitment to our region that requires some facilitated consensus among all of us. Trickle-down approaches alone won’t result in this improved metropolis we imagine. We need to pivot from business as usual and consider “trickle-up” equity approaches as a core part of economic development in our region.

[i] Li, Huiping, Harrison Campbell, and Steven Fernandez. “Residential segregation, spatial mismatch, and economic growth across US metropolitan areas.” Urban Studies 50.13 (2013): 2642–2660; Benner Chris, and Manuel Pastor. “Brother, can you spare some time? Sustaining prosperity and social inclusion in America’s metropolitan regions.” Urban Studies 52.7 (2015): 1339–1356.