Someone once suggested to me that the simplest way to describe an urban planner’s job is that we “decide where to put stuff." As in, urban planners help city officials, developers and communities make decisions about how to use land for specific purposes, whether it’s retail, housing, parks, offices or manufacturing.

It’s a bit of a generalization, but also kind of true. Planners may often lack implementation authority, but their plans and policies have guided the development of cities throughout history—for better or for worse. For example, when Chicago’s comprehensive zoning policy was enacted in 1923, it encouraged the locating of industrial facilities near minority neighborhoods and exposed minority communities to a disproportionate share of environmental pollution. Ultimately, the policy impacted the economic opportunity of minority homeowners.

As a planner, I'll be the first to admit: we don't always get it right.

But it’s not just planners. For decades various powers in the Chicago region—including real estate professionals, politicians, institutions and, yes, planners—made decisions about where development and investment should be focused and often determined who is, and is not, allowed to live and engage in those environments.

Restrictive covenants pushed to keep black families from moving into desirable communities; redlining by banks limited access to mortgages and financial capital; real estate “steering” guided investment away from black communities; and urban renewal destroyed many communities in an attempt to address urban blight. These decisions and policies created legacies that continue to shape the cities we live in today.

While many of these practices have been declared illegal, their legacy, along with existing structures such as zoning codes and urban sprawl, continue to have important implications for both racial and economic segregation in the Chicago region. And as my colleague Marisa Novara pointed out, “It only makes sense that taking steps to deconstruct segregation must be just as deliberate as those taken to create it.”

As we launched our Cost of Segregation work at MPC, one of the questions we’ve asked is how our region’s land use decisions today may perpetuate segregation. And on the flipside, how they can be used to encourage integration, with a mind towards equity and inclusion. Our ultimate goal is to identify a set of policy recommendations that could be implemented to reverse the structural cycles of segregation, reduce the effects of racial and economic isolation and move the region toward greater integration in the future.

There’s so much to talk about on this topic as it relates to land use specifically – where to start?

Below are some broad thoughts on foundational ways planning and regulating land are related to economic and racial segregation. These may point us toward strategies for removing barriers to integration.

Urban Sprawl and Neighborhood Disinvestment

Issues of white flight and suburban sprawl helped perpetuate systematic segregation in the 20th century. Today sprawl continues to be a problem, but we don’t necessarily think of it as a “white flight” issue. In fact, demographics of the suburbs are rapidly changing, and the Chicago region continues to expand outward despite research showing that the pushing out of the urban frontier in a metropolitan area is closely tied to segregation and poverty in urban neighborhoods.

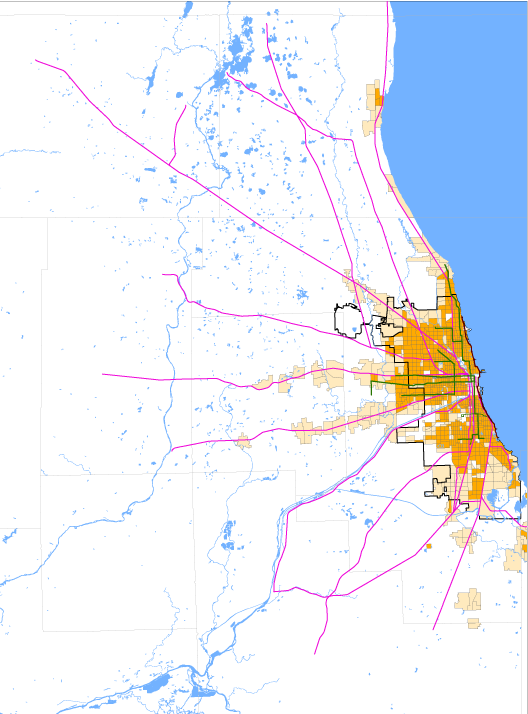

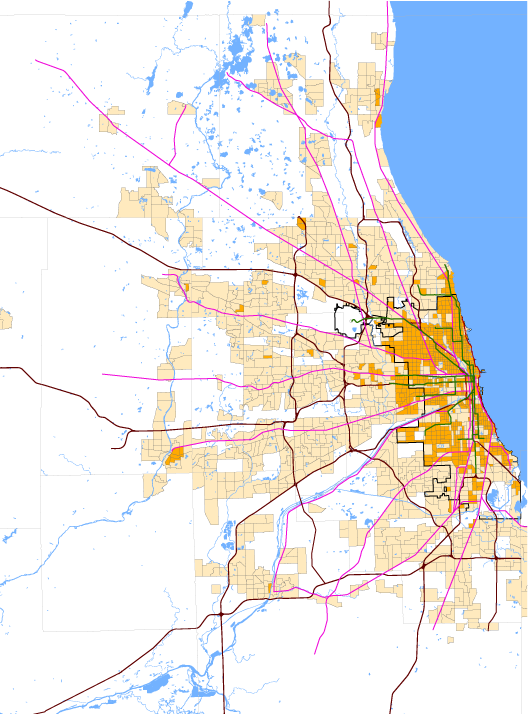

The maps below show how the Chicago region has expanded since 1950. While the region has grown by 4 million people since 1950, the City of Chicago has lost nearly 1 million people over that same period.

Chicago region development 1950

Chicago region development in 2013

Sprawl happens when development outpaces population growth, resulting in a more dispersed population living in areas of low-density development. Regions suffering from sprawl often have a housing-jobs mismatch and lack adequate transportation and transit connections. This not only creates an environment that makes upward mobility more difficult for individuals living in areas of “sprawl,” but it is also linked to population loss and disinvestment in the inner city and inner ring suburbs as development focuses on the periphery.

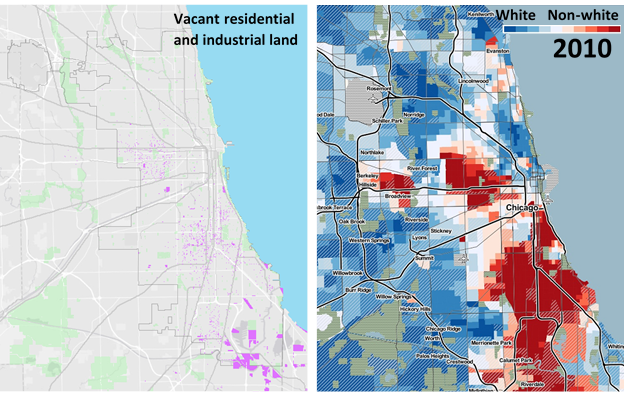

One way we see this play out is in terms of the large swaths of vacant land sprinkled throughout some of the city’s poorest, most segregated neighborhoods. Industrial and commercial disinvestment has also left large swaths of post-industrial land in our region underutilized for jobs and economic development. The map below shows vacant housing and post-industrial parcels in the City of Chicago next to a map illustrating the racial composition of those areas.

While many view this vacant inner-city land as a problem, it could be our region’s greatest advantage if planned for strategically. We’ve certainly heard our counterparts in New York and San Francisco say they wish they had this much developable land – especially near transit.

As the region creates its next comprehensive plan, ON TO 2050, there is a need to ensure that equity goals are infused within the region’s growth agenda. Research shows that regions that restrict sprawling development, promote policies that protect undeveloped land and carefully plan metro-wide transportation systems are less segregated and more prosperous.

Part of the solution may lie in urban growth boundaries, which have been adopted by other cities around the country. In Oregon, for example, each of the state’s cities and metropolitan areas has created an urban growth boundary around its perimeter, which controls urban expansion into farm and forest land and promotes the efficient use of land inside the boundary. Could the Chicago region benefit from a growth management strategy like this one?

Strategies that promote a shift in development patterns to address environmental, health and economic disparities could help drive investments in the region to where they would most improve access to opportunity for residents in segregated places – and perhaps start to turn some of this vacant land into productive, vibrant uses for those communities.

MPC is exploring strategies to curb uncontrolled suburban development and sprawl through expanding protection of land and restricting growth in areas where development has not yet occurred, such as in unincorporated Cook but also unincorporated areas in other counties. We’re also soon launching a new initiative focused on this issue of vacant and unproductive land in the region – how much is there and what can we do about it?

Land use regulation and zoning

One way in which public officials regulate land is through the zoning code. Land use and zoning regulations determine the allowed uses of a specific parcel of land and the density and size of development that can be built there.

It’s a powerful tool that shapes communities, with the potential to create vibrancy and economic opportunity. It’s also a tool that has been used to exclude specific kinds of housing stock and certain types of people from a given community, leading to the continued racial and economic segregation we see today.

Research shows that land use regulation and anti-density zoning fosters segregation and inhibits desegregation over time.

To see what I mean by “exclusionary” zoning policies, here are some examples:

- Restrictions on density can limit the supply of housing in a given area and favor the development of single-family homes that may be unaffordable for low-to-mid income families. Most of Chicago’s zoning code allows for only single-family homes to be built or makes it nearly unaffordable for a developer to build a multi-unit building with affordable housing given the allowable density. Density restrictions also encourage the tear down of multi-family buildings for single family homes in wealthier neighborhoods, further diminishing supply and inhibiting integration. Time and time again we’ve seen opposition to density used as a way to wall off wealthy communities and enable their isolation.

- Minimum parking requirements can also impact the affordability of housing and inhibit integration. In the City of Chicago, 98 percent of residential land actually requires 1-2 parking spots per housing unit, despite the fact that over 25 percent of households in Chicago don’t even own a car. This takes up precious square footage for parking instead of apartment units which might make those units more affordable. Parking can increase the price of units up to $20,000 per surface space, $50,000 per structured space and $80,000 per underground space, according to data from TransForm. Since parking spaces are typically attached to units when they’re sold or rented, that’s like adding up to $80,000 per unit.

- Minimum lot sizes, or restrictions on how small a lot can be for a housing unit to be built on it, prevents the building of smaller, more affordable housing units. Larger lots are also generally more expensive.

These are just a few examples of how the zoning code can implicitly exclude low-to-middle income individuals from accessing affordable housing in areas of opportunity.

Removing these zoning policies also removes barriers to housing affordability and can promote integration. Inclusionary zoning can help ensure housing affordability across neighborhoods and mitigate displacement in neighborhoods in the early stages of gentrification.

We’ll be digging into the City of Chicago’s zoning code more, and zoning codes of municipalities across the region, with the goal of identifying and developing focused recommendations to ensure that the way we are planning today is not complicit in allowing the continued stratification of people by race and income across the region.

Next Steps

Urban sprawl and zoning are only two ways in which our modern land uses policies may continue to foster segregation and disinvestment.

I didn’t even mention how our region has continued to isolate affordable housing from employment opportunity and the transit assets that connect the two. Nor did I address how the valuation and devaluation of land and real estate is implicitly biased, and a barrier to wealth accumulation for black and brown communities (we’ve tackled this in a different post). And I could have spent a big chunk of my word count on issues of property taxes in our region and how they create instability and insecurity for long-term residents and business owners in areas facing gentrification.

These things are all related to the relationship between land use and racial and economic segregation.

My amazing colleagues and our team of advisors at MPC have done a lot of work to determine what segregation costs the Chicago region. (Hint: It’s a lot). Their research also points us toward a hopeful future – one where a more integrated region means a stronger economy, greater educational opportunity and increased safety and security for all.