The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) tackles inequality through its landmark Cost of Segregation initiative. This initiative has gained traction in the local media and the national consciousness alike, as elected officials and residents start frank conversations on the impact of income and racial inequality. Working in development, I’ve become intimately familiar with the statistics. Statistics are important. They have a way of distilling the intangible into a set of easily digestible facts. But the impact of segregation and divestment is truly felt in your feet, walking through communities.

Chicago’s South and West Sides often are named as the poster children for the region’s rampant inequality. While this rightly merits our concern, poverty is growing fastest in the suburbs. The suburbs are diversifying at a rapid rate, absorbing many of the same issues as Chicago, but without the population or tax base to marshal adequate resources. As a public servant and photographer, I feel compelled to explore and know my region. I wanted to see how a city like Waukegan, which grew up independent but is now firmly in Chicago’s orbit, is faring. This past weekend, I hopped on the Union Pacific North train from the Ravenswood stop to the end of the line.

Look for the Tumbleweeds

Walking through downtown Waukegan, it’s hard not to feel like something’s amiss. Empty storefronts announce their vacancy in large bold letters. The new(ish) shopping center offers tenants the “First 6 months Free!” Even the newly restored Genesee Theater, that hopeful engine of redevelopment, is flanked by empty store windows. It’s noon on a Sunday, and on my particular street, I’m completely alone. It’s another full two minutes before a car even zips by.

I pop into one of the few remaining businesses, a coffee shop. Instead of being greeting with the customary “Hi, how are you?”, I get a surprised, “Oh!” A Katy Perry playlist echoes in the cavernous space. The cashier looks sullenly at the ground. I pay for my Gatorade and leave. As I turn down MLK Ave from Washington I’m struck by the hulking new addition to the Lake County Court rising skywards. The glassy Waukegan City Hall likewise clashes with earth-toned, century-old churches and Lake County’s Brutalist concrete monoliths. There, on Grand, the McDonald’s is starting to fill up. It’s the one business with a pulse.

Despite its shoreline location, Waukegan is not connected to its water.

I arrived on the Metra train to a station abuzz with neon-clad teens eagerly awaiting the Spring Awakening festival. While that small hub of activity glowed with youthful energy, not one of them found their way downtown. Despite its shoreline location, Waukegan is not connected to its water. The underused Amstutz Expressway, known locally as the “road to nowhere” is a multi-lane dividing line. Beyond the expressway, a gauntlet of train tracks further complicate lake access. Where the Amtrak terminates, there is simply no easy way to the harbor. Even getting from the train to downtown requires crossing off-ramps and tight-roping a narrow strip of sidewalk. Invaluable lakefront land is gobbled up by three superfund sites, which will require substantial remediation prior to productive use. A ten-minute walk over highways and through train tracks rewards me with a harborside hotdog stand, a baitshop and a seasonal ice cream shack. Certainly not a destination in its own right.

I don’t know the city well enough to answer: Is all of Waukegan like this? Is downtown the anomaly here? Are there thriving, vibrant business districts outside of downtown? How can Illinois’ 9th largest city and the county seat for a county with over 700,000 people be crumbling from benign neglect? Perhaps this is a harsh assessment, but I’m troubled by what I see.

Cheek and Jowl

I was last in Waukegan in 2009 during the height of the Great Recession. Aside from the new County Court, Waukegan is a city frozen in time. I recall the same disorienting isolation, the same deeply unsettled feeling of neglect. I remember the whipping, lake-tinged November wind far colder than the announced 45 degrees.

At the time, I was a bank teller in tony Lake Bluff. Lake Bluff’s three-block downtown was always full of diners and shoppers, freshly painted buildings and shaded patios. Old money mansions extended eastward towards the bluff overlooking an aquamarine Lake Michigan. Two days a month, the 1st and the 15th, I was posted at the bank’s North Chicago Branch. Aside from those days, the bank was slow business. Those other two days, everyone cashed their checks and left without deposits. Adjacent to the bank, ambitious weeds poked through sun-baked asphalt.

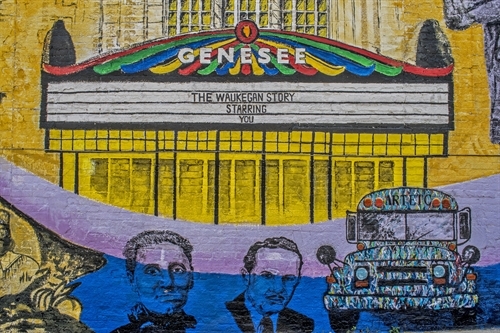

A mural of Waukegan's carefully restored Genesee Theater Matt Altstiel

Such is the extreme polarity of Lake County. Home to the likes of Lake Forest, Lake Bluff and Highland Park—Lake County is the nation’s 31st wealthiest county according to the 2010 Census. This concentrated generational wealth is readily apparent walking through finely manicured streets, past specialty store windows offering up European wines and cheeses. Those wealthy communities are beautiful mix of leafy trees, lovingly maintained brick and stucco buildings and gleaming late model luxury cars.

Immediately north, the communities of North Chicago, Waukegan and Beach Park are the inverse. Where segregation is largely a neighborhood phenomenon in Chicago, it’s a city by city process in the suburbs. Lake County is perhaps most jarring, as the UP-North train passes through the nation’s most exclusive zip codes and some of its most marginalized. Waukegan has tried to jump start its downtown, banking on the lavishly restored Genesee Theater. Even as the venue commands some admirable headliners, the type of dining experiences adjacent to comparable venues do not exist. In downtown Waukegan, at least, the needs are manifold. When people can’t spend their money in North Chicago, Waukegan or Zion—they’ll spend it in Gurnee, Lincolnshire and Libertyville. Dollars go out, they do not come in. Consequently, downtown lacks the people, the jobs and the amenities it needs to rebound.

Where segregation is largely a neighborhood phenomenon in Chicago, it’s a city by city process in the suburbs.

Takeaways

I am not an urban planner, although as of April 2017, at MPC, I am surrounded by them. I don’t personally know the economic costs to revamp infrastructure and jumpstart downtown. I don’t know what magic bullet of retail, employment and residential will make downtown a place where people work, play and stay. But I do know that a resurgent Waukegan requires overcoming substantial physical and psychological barriers, a long-term project of equal parts love and patience.

This is the paradox and the promise of Waukegan: It has coveted commuter rail, an enviable perch on Lake Michigan, intriguing century-old architectural gems and is the county seat for the state’s third most populous county. And yet, seemingly no one is investing here. The distance between vibrant past and unfulfilled present grows ever wider. As I whip through the verdant North Shore, the question is inescapable: Can Waukegan come back? And do we as a society care enough to reinvest in increasingly marginal places like it?