Aldermen and community residents have an important role to play in how affordable housing goals are met, not if they are met.

Image courtesy Alex Nitkin/DNAinfo Chicago

Protesters and supporters of a proposed 100-unit development in the 45th Ward

A frequent mantra in community development is “the community is the expert.” A welcome—and needed—change after a history of top-down development, the rise of the community development movement starting in the late 1960s embodied the wisdom of centering decisions in the hands of local leaders who had long been denied avenues to determine the fate of their own neighborhoods.

More and more I am seeing... “listening to the community”... being used to justify highly questionable decisions.

As a former community-based affordable housing developer, I come from that tradition, and in the right context it can be a powerful approach.

More and more, however, I am seeing “listening to the community” held up as the decision-making North Star when it’s actually being used to justify exclusionary and even racist decisions. What then?

First, some history

We’ve been here before. In his book, The Color of Law, Richard Rothstein details how for decades, strict segregation was enforced by officials citing “local resentment” toward integration as their rationale.

In the early 1970s when the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) suggested low-rise, scattered site public housing in predominantly white areas, then-Mayor Richard J. Daley rejected the proposal on the grounds that such housing—sure to have black tenants—should not go where it would not be “accepted.”

Rothstein notes that while CHA proposed constructing public housing units in majority white areas, “each project was subject to veto by the alderman in whose ward it was proposed.” The result? As the district judge who reviewed the case reflected, “No criterion, other than race, can plausibly explain the veto of over 99.5 percent of the housing units located on the white sites…and the same time the rejection of only 10 percent of the units on Negro sites.”

The federal government had long been “planting the seeds of Jim Crow practices… under the guise of ‘respecting local attitudes.’”

These local attitudes have long been supported at the federal level. In 1973, President Richard Nixon stated that public housing should not be imposed upon white communities that didn’t welcome it, and showed the door to HUD Secretary George Romney for having the temerity to attempt to enforce the Fair Housing Act’s anti-segregation edicts. The subsequent Ford Administration’s solicitor general defended Chicago’s placement of public housing in ways that furthered segregation this way: “There will be enormous practical impact on innocent communities who have to bear the burden of the housing, who will have to house a plaintiff class from Chicago, which they wronged in no way.” (emphasis mine)

Here we have the federal government framing the notion of an equitable distribution of affordable housing across a jurisdiction as punishment unfairly imposed upon blameless communities—but only those that happen to be white. The federal government has long been “planting the seeds of Jim Crow practices… under the guise of ‘respecting local attitudes.’”

Research shows more entities, more segregation

There is a troubling correlation between the number of public sector entities making land use decisions and levels of segregation. Empirical research has shown that across metros, the higher the number of jurisdictions, the higher the level of income and racial segregation. For example, a 2016 study found that the greater the level of involvement by local government and residents in development approval, the greater the segregation, concluding that “land use decisions cannot be concentrated in the hands of local actors.” (Lens and Monkkonen, Yang and Jargowsky, 2006)

Chicago’s 50 Aldermen in perspective

What does this have to do with the city of Chicago? The answer can be summed up by the headline of a recent Reader article, “How’s Chicago supposed to desegregate when developments with affordable housing can be blocked by aldermen on a whim?”

The higher the number of jurisdictions, the higher the level of income and racial segregation.

Anyone who knows Chicago politics knows that our 50 Aldermen maintain near-total control over zoning changes and development approvals in their wards. In other words, contrary to the warning above, our land use decisions are heavily concentrated in the hands of local actors.

Consider that New York City had 8.5 million inhabitants in 2016 and 51 city council members. Los Angeles clocks in 3.9 million residents with 15 city council members. As the third largest city with 2.7 million, each of Chicago’s 50 Aldermen represent 54,000 residents. New York City, in contrast, has one council member for every 166,666 residents and LA has one for every 264,666. Another way to put it: New York City has 5.8 million more residents than Chicago, but just one more city council member.

The result of such a high number of decision-makers per capita? Zoning and land use decisions concentrated in the hands of 50 local actors, with plenty of opportunity to ‘respect local attitudes’ at the hyper-local level.

A Northwest Side case study

GlenStar

A rendering of the proposed Northwest side development near the Cumberland Blue Line stop

This is what plays out in Maya Dukmasova’s piece in the Reader: a developer proposes a nearly 300-unit building with 10 percent affordable units near O’Hare and the Cumberland Blue Line stop. While the Alderman was initially supportive, after intense opposition to an affordable development in nearby Jefferson Park targeted to veterans and people with disabilities (marked by protesters with signs reading ‘Cabrini started as vet housing too,’ a reference to Chicago’s Cabrini-Green public housing development which had 3,600 units; the Jeff Park development proposed 100), he withdrew support and asked the Zoning Committee to delay the matter indefinitely. The project, which proposed 30 affordable units on site—7.5 percent more than the ARO requires—was deferred by the Zoning Committee and has not advanced.

Policies that are racially neutral may still be in violation of the Fair Housing Act if their impact is discriminatory, regardless of intent.

The reason for both the Alderman's lack of support and the Zoning Committee's agreement to delay? Deference to local control. When the developer recently sued the City for blocking the development, the Alderman's Chief of Staff explained his lack of support this way: "Ultimately it comes down to local residents and their feedback. The Alderman is ultimately focused on what his ward wants and what the residents want and don't want."

As for the Zoning Committee, the reason for the go-along is the city’s long-standing practice of aldermanic prerogative. The City Council version of deferring to local interests, it is described by a spokesperson for the chair of the Zoning Committee as the reason for that body's deferral: "(The chair) greatly respects his colleagues and the fact that they have been chosen by the voters to represent them. On matters of zoning changes, the Chicago City Council has always given great deference to the Alderman of the ward where a change is requested."

Indeed.

Except that times are changing. The 2015 Supreme Court case, Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs v. The Inclusive Communities Project, ruled that policies that are racially neutral may still be in violation of the Fair Housing Act if their impact is discriminatory, regardless of intent.

I am not arguing that everyone who opposes affordable housing does so with racist intent. What I am saying is that intent is irrelevant.

In other words, regardless of whether opposition is framed in neutral terms of concerns about density, parking or school crowding, if the impact is discriminatory it can still be illegal. At the many hearings I attended in support of the Jefferson Park proposal, I heard those in opposition state over and over that their objection was not based in racial animus; rather, that they truly were concerned about traffic or tall buildings or school enrollment.

It is not my place to judge their motivations, and the truth is that it doesn’t matter.

I am not arguing that everyone who opposes affordable housing does so with racist intent. What I am saying is that intent is irrelevant. Why? Because even without conscious racist intent, the impact of one's actions can be racially discriminatory.

If we agree to set aside intent and focus on impact, what do we find? In this Cumberland example, we find the

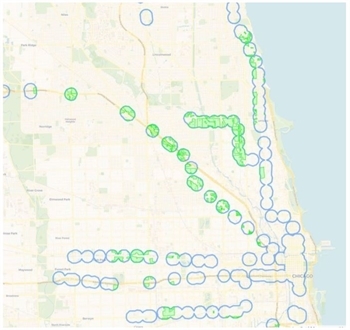

Steven Vance/Chicago Cityscape, using zoning map data from the Chicago Department of Planning & Development

Single Family Zoning near CTA Stations: Multi-family units are not allowed in green areas

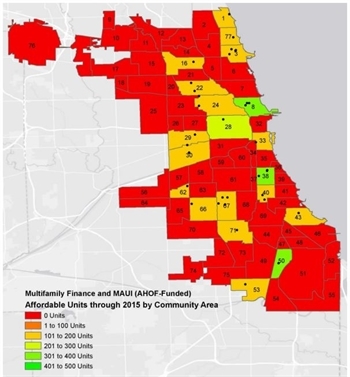

loss of 30 affordable units in a ward in which 45 percent of renters are paying more than the recommended 30 percent of their income in rent. Expanding out from this specific example, nearly half of adults living in Chicago are spending more than they can afford on their homes or apartments. This cost burden and shortage of affordable housing—especially for low-income residents—is experienced in all 50 wards and 77 community areas spanning the city of Chicago. In higher-cost areas, the shortage is particularly stark due to local and political opposition, higher costs for land, and zoning laws that limit multi-family development. The city’s Inspector General recently found that of the 1,623 affordable housing units created by the Affordable Requirements Ordinance and Density Bonus fees through the year 2015, there were zero in nearly two dozen North, Northwest and Southwest side community areas.

OIG based on DPD data through December 2015

Paths forward

So what do we do about the lack of affordable housing in many parts of the city? That’s the question we’ve been working through with dozens of advisors in the second phase of our Cost of Segregation work. We can learn from the state of California’s recently passed Senate Bill 35. Effective January 1, 2018, the law requires cities that have not yet met affordable housing targets to streamline and more quickly approve developments with minimum levels of affordability, even if there is local opposition to them. The bill’s fact sheet explains:

When local communities refuse to create enough housing—instead punting housing creation to other communities—then the State needs to ensure that all communities are equitably contributing to regional housing needs. Local control must be about how a community meets its housing goals, not whether it meets those goals. Too many communities either ignore their housing goals or set up processes designed to impede housing creation.

How might this thinking be applied at the city level? Just as California has done with each city, we could establish a minimum level of affordability desired for each ward; let’s say 10 percent. (This is the threshold used for Illinois’ statewide Affordable Housing Planning and Appeals Act; gutted of any enforcement mechanisms, its ineffectiveness is a cautionary tale. We’ve written before about ways this law could be improved).

Here's how it could work: When a residential development with at least 10% affordability is proposed in a ward with less than 10% affordable housing, said development can no longer be rejected or delayed indefinitely by the Alderman. In a new streamlined process, the Alderman can still shape the development and request changes, but no longer has complete veto power over the project moving forward. Enacting a streamlined approval process would ensure that projects don’t languish simply by dragging them out over long periods of time, forcing developers to abandon their plans without ever actually being told no. Most importantly, it would generate more affordable housing choices near jobs and transit.

This idea is neither radical nor ambitious enough. But it is one avenue to address the structures that reinforce our separation. Over the past two and a half years, we’ve worked with more than 100 advisors to outline near-term strategies to reduce our region’s segregation and increase equity. We will share these strategies later this spring, and while no single idea is a silver bullet, taken together, we have definitive steps we can take to become a more equitable, inclusive region.

Our policy of deferring to local decision-makers matters that should be city-wide policy has a similar impact as previously more overtly discriminatory practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants.

Aldermanic prerogative seems as old as the city itself; it is part and parcel of what Chicago is. Many people I've shared this proposal with have reacted with bemusement - almost as if I'm suggesting Chicago no longer be located along Lake Michigan.

But we are a city with profound residential segregation. Our practice of deferring to local decision-makers matters that should be city-wide policy has a similar impact as previously more overtly discriminatory practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants. We are creating a disparate impact on protected classes of people, and on our city and region as a whole. As former Newark Mayor Cory Booker said, "We should not be putting civil rights issues to a popular vote, to be subject to the sentiments and passions of the day." If we are serious about being an equitable city, aldermanic prerogative cannot be sacred.