A Brief History of the Fight for Equitable Education in Chicago

MPC Vice President Marisa Novara introduces the film '63 Boycott to a full house. | Photo by Liz Granger

On October 22, 1963, more than 250,000 students boycotted the Chicago Public Schools (CPS) to protest racial segregation. It's noted as one of the largest student demonstrations ever staged. And it sparked a wave of similar civil rights actions in cities across the United States, including school boycotts in New York City, Cleveland and Seattle.

In honor of the 55th anniversary of this historic event, MPC and Kartemquin Films hosted a film screening of '63 Boycott on October 22, 2018. The 30-minute documentary connects the 1963 CPS Boycott to today's education struggles.

Here's a brief overview at how parents, teachers, students and activists in Chicago have fought to ensure equitable education for all of the city's youth, along with some additional reading materials that'll help you take a deeper dive into this issue.

Demanding quality education for all of Chicago’s youth

Racist education policies in Chicago helped maintain segregated and unequal schools for decades. In fact, the United States Civil Rights Commission released a report in 1962 stating that the city’s public schools were “an example of rank de facto segregation in the northern metropolises.” The report also revealed that roughly 90 percent of black elementary students and 63 percent of black high school students in Chicago attended schools that were more than 90 percent black.

Photo courtesy of Kartemquin Films

1963: "Freedom Day"

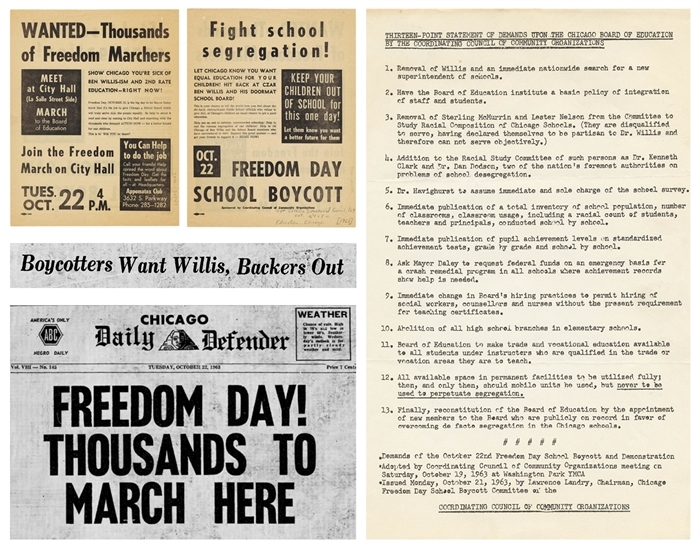

Tired of inferior, segregated, and overcrowded schools, community members began organizing resistance. The Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO) took the lead, organizing “Freedom Day,” a mass boycott and several demonstrations. Fliers for the 1963 boycott (top left) called on people to keep their children out of school and meet at the Appomatox Club on “South Parkway,” which later became King Drive.

The Boycott had a list of 13 demands (right), including the institution of policies to promote integration and a public inventory of racial demographics (school by school). Local publications, including the Chicago Tribune and The Chicago Defender (bottom left) covered the boycott plans and published the list of demands.

Photos courtesy of Kartemquin Films, the SNCC Archive at the Woodson Library and the Chicago Urban League

Pushing for equal representation and integration

Parents and students in Chicago expressed the desire to have a more diverse and representative school administration that would embrace integration. Chicago Public Schools (CPS) Superintendent Benjamin Willis, who ran the school system during this period, was known for maintaining an “intransigent position on integration in the city’s public schools.” By the beginning of 1964, Willis had become the central target of the fight for equtiy in Chicago's schools. The call for his resignation or removal remained the movement's number one demand (as pictured in one of the boycott signs) until he resigned in 1966.

Photo courtesy of Kartemquin Films

Taking it to the streets

The march originated at neighborhood schools from all sides of the city: South (Chinatown), West (East Garfield Park), and North (Lincoln Park). At 4:00 p.m., all of the marchers converged downtown for a rally outside of the Chicago Board of Education headquarters at City Hall. Estimates place the total of number of protestors at 20,000.

Photos courtesy of Kartemquin Films

“Something Better for Our Children”

The 1963 boycott was one of the largest demonstrations of the Northern Civil Rights movement. Using nonviolent means, the community made their voices heard. It was largely considered a success, bringing national attention to the situation in Chicago and highlighting the fact that segregation and inequality were not strictly Southern issues.

Photo courtesy of Kartemquin Films

Public reactions to the boycott

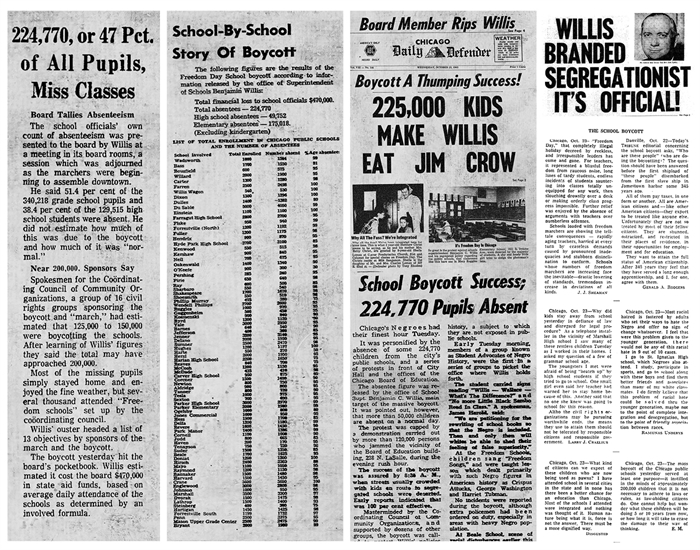

Nearly 225,000 students were reported by the school board as absent on “Freedom Day.” The Chicago Defender ran a school-by-school tally of absenteeism the day after the boycott. While The Defender’s columns took a more positive spin on the boycott, the public opinion column in the Chicago Tribune on October 25, 1963 (bottom, far right) revealed a wide range of public reactions to the protest.

Photos courtesy of Kartemquin Films

The push for equal education across the nation

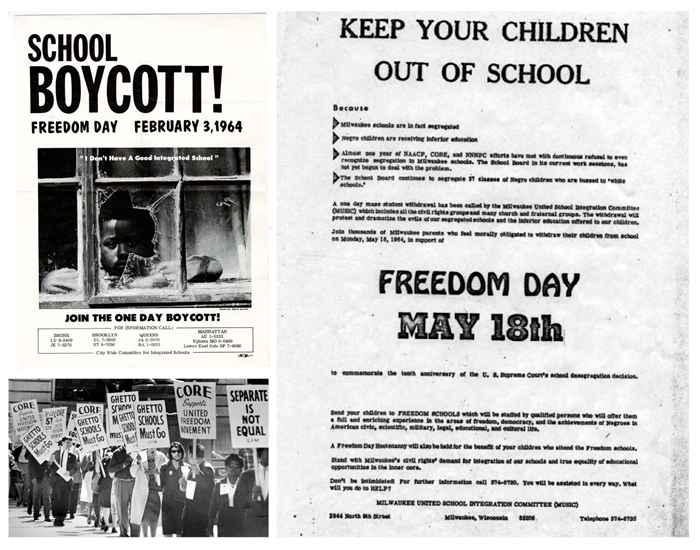

Negotiations between Civil Rights organizations and the City of Chicago began soon after the boycott, but they eventually fell apart, which gave way to “Freedom Day II,” another massive boycott in February 1964. This became part of a wave of community activism to desegregate schools across the country.

On February 3, 1964, more than 460,000 students, predominantly black and Puerto Rican, stayed out of school to protest educational inequality and school segregation in New York City. On April 20, 1964, an estimated 60,000 black students in Cleveland Public Schools also boycotted for equality. On May 8, 1964, a one-day boycott of predominantly Black schools took place in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, on the 10th anniversary of the U.S. Supreme Court’s Brown v. Board of Education decision. About 11,000 students (roughly 60 percent of the city’s black, inner-city school population) stayed out of school as part of the demonstration organized the Milwaukee United School Integration Committee (MUSIC).

In the numerous school boycotts that took place across the U.S. in 1964, the message was clear: “Jim Crow must go.”

Photos courtesy of the Queens College Department of Special Collections and Archives (Elliot Linzer Collection) and the Wisconsin Historical Society

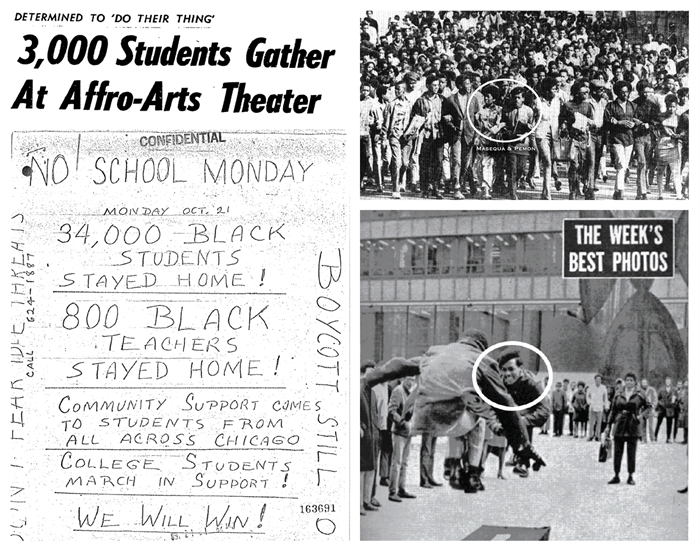

The 1968 CPS high school student walkouts

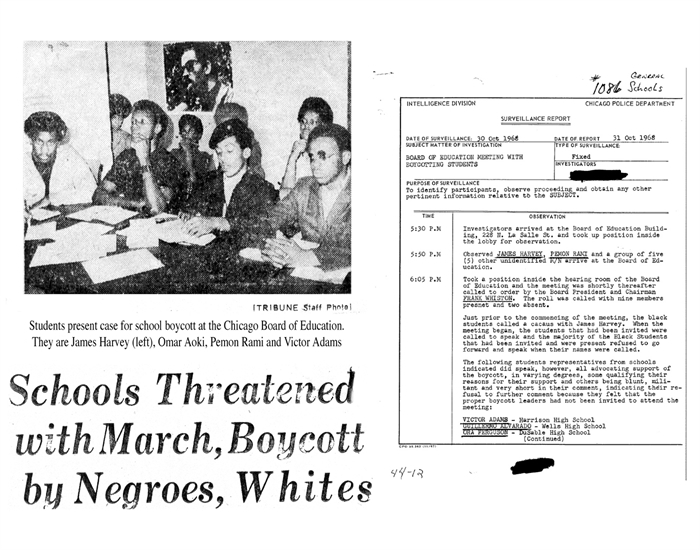

In 1968, Chicago high school activists conducted a series of city-wide “Black Monday” school walkouts for three weeks straight. These demonstrations, which eventually included 35,000 students, were an expression of growing dissent among the city's black and Latino student population. These student activists had a list of 12 demands, including black and Latino teachers and administrators, ethnic studies classes and clubs, and bilingual education.

From the collection of Pemon Rami

Youth Activism: Determined to “do their thing”

Then 18-year-old Pemon Rami, a recent graduate of Wendell Phillips Academy High School was one of the main organizers of these walkouts. At the Civic Center Plaza, he and several other students theatrically smashed a wooden coffin labeled “Board of Education.”

The Chicago Defender was once again instrumental in covering this fight for more equal education in the city. Many of the students involved in these protests faced violence, intimidation, disciplinary actions, and arrest, but their efforts led to greater numbers of black and Latino teachers, counselors, and administrators being hired, and allowed the creation of ethnic studies classes and clubs.

From the collection of Pemon Rami

The fight for educational equity continues

On the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington (and just two months shy of the 50th anniversary of the 1963 Boycott), almost 500 students, parents, teachers, and activists boycotted school and marched on CPS headquarters and City Hall. Organized by community groups, including Kenwood-Oakland Community Organization (KOCO) and Action Now, the primary objective of the protest was to call for an elected school board. The march concluded with members of the protest being admitted to a meeting of the CPS School Board.

Photo courtesy of Kartemquin Films

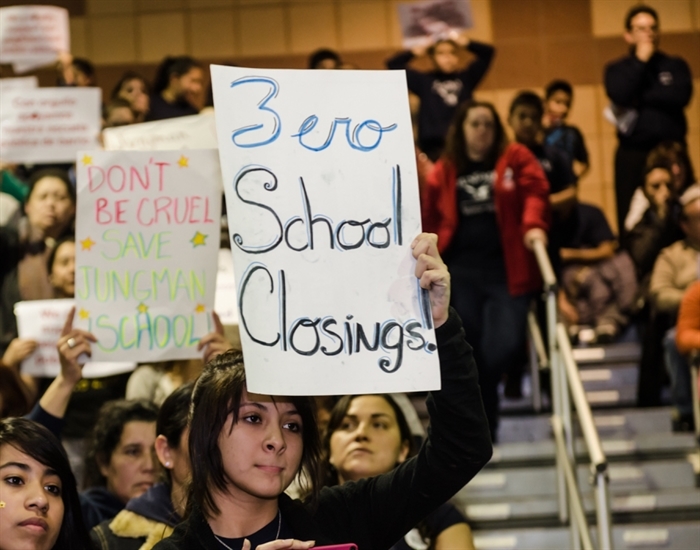

The disproportionate impact of school closings

On April 24, 2013, close to 300 Chicago students boycotted school and marched on CPS headquarters, in protest of the proposed closings of schools in predominantly black and brown neighborhoods, as well as the overuse of standardized testing to determine school and student performance.

In June 2013, nearly 50 schools were closed in a sweeping move. The community was outraged and confused at the disproportionate impact of the closures on black communities: Eighty percent of the students affected by the shortlist closures were black. A 2018 study at the University of Chicago found that the closures had had no educational benefits.

Photo: © Sarah-Ji, Pilsen, 2013

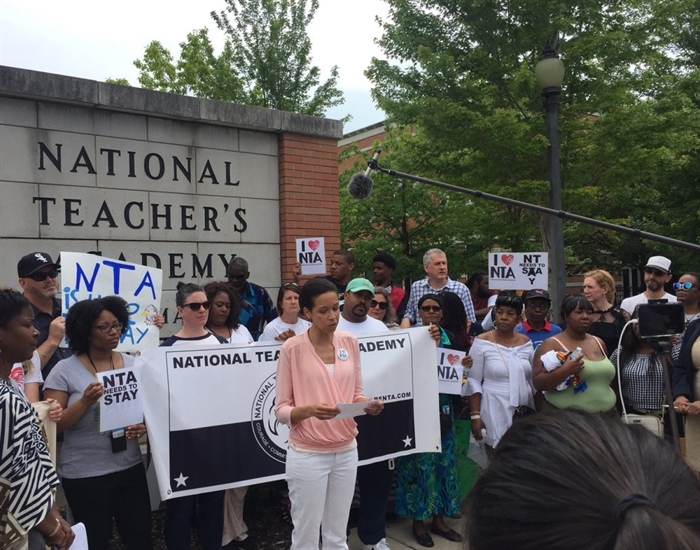

#SaveOurSchools

CPS is the still most segregated big-city school district in the U.S. As a result, black and brown students continue to face the deep-seated racism their predecessors faced. Since last year, Englewood students have protested the proposed closure of four neighborhood high schools. And more recently, parents, teachers and students from National Teachers Academy (NTA), a majority-black, elementary school, partnered with Chicago United for Equity—a nonprofit organization that promotes racial justice in schools and communities—to continue the legal fight against the CPS plan to convert NTA into a high school for communities near the South Loop. A judge will rule on the matter in December 2018.

Photo courtesy of the Chicago Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights

For More Information

Did you or a family member participate in the 1963 CPS Boycott? Boycotters are being located through the documentary project’s interactive website 63boycott.com. Kartemquin also invites those that participated in the 1963 CPS boycott to contact them through the website, by sending an email to 63boycott@kartemquin.com, or calling them at 773.413.9263.

Recommended Reading

Elizabeth Todd-Breland, A Political Education: Black Politics and Education Reform in Chicago since the 1960s, 2018

Adeshina Emmanuel and Yana Kunichoff, "In one Chicago neighborhood, three high schools offer dramatically different opportunities," Miseducation series, Chalkbeat, October 16, 2018

Tanner Howard, "1968 Student Uprising," Chicago Reader, October 4, 2018

Matt Harvey, "Stewart Elementary School," Chicago Reader, August 21, 2018

Eve L. Ewing, Ghosts in the Schoolyard: Racism and School Closings on Chicago's South Side, 2018

UChciago Consortium on School Research, School Closings in Chicago: Staff and Student Experiences and Academic Outcomes, May 2018

Sarah Karp, "Dashed Hope: How A Once Proud Chicago High School Hollowed Out," WBEZ, February 20, 2018

Kalyn Belsha, "Empty schools, empty promises" (series), The Chicago Reporter, 2017-2018

Alden Loury, Black students declining at Chicago's top public high schools and in CPS overall, August 21, 2017

Dionne Danns, Desegregating Chicago's Public Schools: Policy Implementation, Politics, and Protest, 1965-1985, 2014

Rachel Dickson, 1963 Chicago Public School Boycott, WTTW Chicago Tonight, October 22, 2013

Ben Joravsky, "Remembering Chicago's great school boycott of 1963," Chicago Reader, May 20, 2013