Black and white image of a hand inserting a vote into a ballot box

The day before the midterm elections, pollsters and analysts are producing exhaustive—and exhausting—analysis about our highly polarized electorate. Stark divides are widening across parties and across geographies. But there is one trend that isn’t diverging.

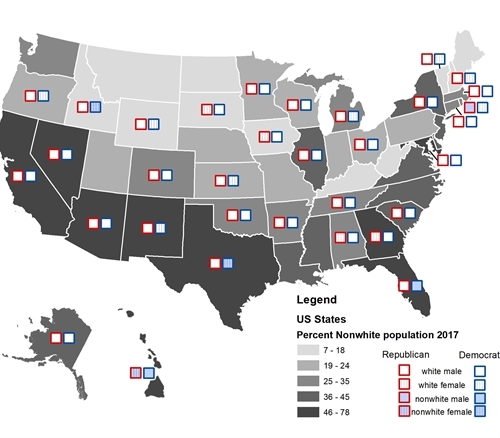

In states across the country, the candidates vying for the most important executive position—the governorship—share stark similarities across the two major parties: they are almost exclusively white, and largely men. Of the 36 states with a gubernatorial election in 2018, 90% of the candidates are white (94% of Republican candidates and 88% of Democratic candidates).

On gender parity, the field fares only a bit better—78% of candidates are men with a notable dissimilarity between parties (89% of Republicans and 67% of Democrats). Are we witnessing a trend away from diversity in our highest states’ executive positions—positions that make crucial budget decisions affecting our cities and metropolitan regions? And, what does this mean for the future of legislation that would address longstanding inequities, like segregation or unequal access to transportation and jobs, or access to key appointed positions of power?

Percent of nonwhite population by US State in 2017 and diversity of 2018 gubernatorial candidates

But as this map makes clear, whether you live in a state that leans Democrat, a state that leans Republican, a state with large shares of non-white population, or a state where that share is growing faster than others, the candidates are overwhelmingly white and male.

Moving down the ballot, there are certainly some encouraging signs of inclusion: we may witness the first Muslim women elected to Congress (Michigan and Minnesota) and the first Native American woman elected to Congress (New Mexico). Tuesday could see the election of the first Black female governor (Georgia), the first openly transgender governor (Vermont). And in our nation’s cities, we are witnessing a larger pool of young and diverse candidates for local offices.

Inclusive political representation that reflects our country’s demographic makeup is a starting point for bridging our political divide. Echoing the current polarized political climate, and the challenges that nonwhites face in political representation, more than half of Latinos (54%) say it has become more difficult in recent years to be Hispanic in the U.S. And, Black voter turnout fell sharply during the last election, from nearly two-thirds to slightly below 60%. Black millennials were the only group in that generation to witness a decline in voter turnout—from 55% in 2012 to 49% in 2016. In fact, in general, the public’s belief that their government is working for them is near a 50-year low.

In Illinois, it was recently reported that Governor Bruce Rauner, a white male, overwhelmingly appointed other white males to a broad array of state positions.

A representational mismatch has serious consequences for the civic health of our states. When diverse populations do not see and feel the government working for them, there is less motivation to participate in civic and political processes.

As I sifted through these disheartening trends, I find myself encouraged by a more diverse field of candidates for Chicago’s City Council. There are indications that the 2019 election will include record numbers of challengers, many of whom are women, people of color, and those who identify as LGBTQ. This is important because city councils are an important feeder for higher positions such as mayor or congressman. Our pivot toward more inclusive representation can begin in our cities. And this is more than purely academic.

MPC’s Cost of Segregation study in 2017 with the Urban Institute quantified how all residents suffer when longstanding patterns of racial and economic segregation remain—a stunning of $4.4 billion in lost income per year. This means fewer dollars for public investments, fewer jobs, and more homicides, if we accept the status quo. Enacting equitable policies to undo our entrenched racism is going to take strong political will and groundbreaking collaboration. It starts in cities like Chicago, which have the power to re-set debates at the state and federal levels.