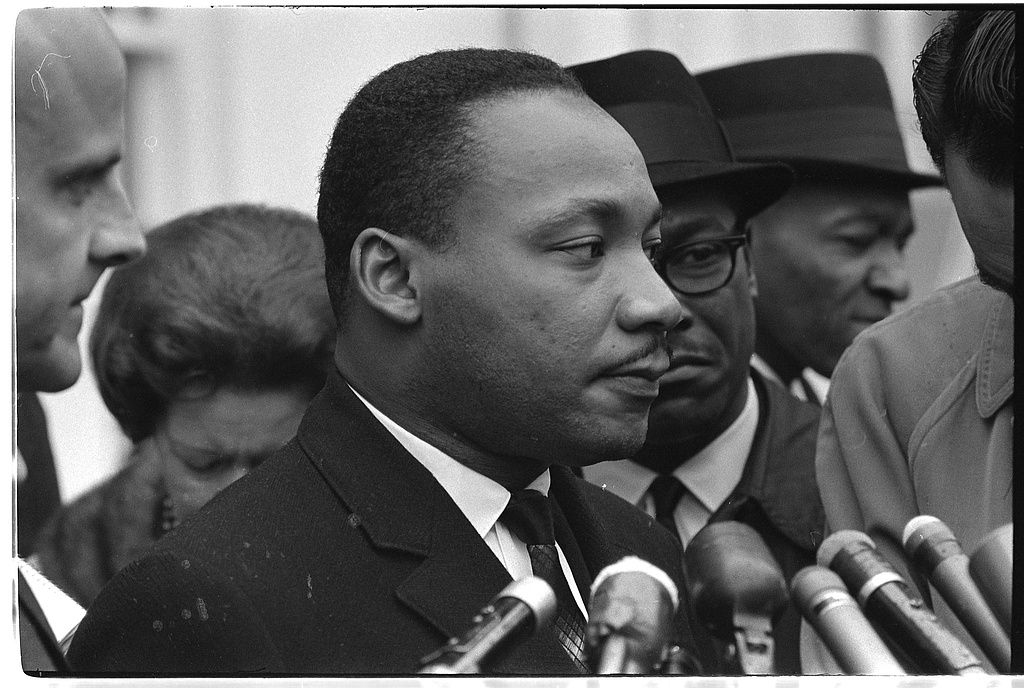

Image courtesy The Library of Congress

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1963, after meeting to discuss civil rights with President Lyndon B. Johnson

In the 1960's, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. met a Chicago that represented America’s deeply rooted history of discrimination, cemented in local and federal policy. Redlining maps show how Federal agencies influenced investment by the racialized mapping of communities. Superhighways reinforced and exacerbated segregated neighborhoods. Black and white children were explicitly separated in school. The size, scale and institutional organization of Northern racism in Chicago was a different challenge than segregation in the South.

The problems Dr. King battled in Chicago decades ago still plague us, from school inequality and segregation to lack of access to quality affordable housing.

After the passage of the Civil Rights Act, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s advocacy shifted from fighting legal racial segregation to pursuing genuine equality in all facets of American citizenship. In advocating for an Economic Bill of Rights, King’s movement embraced full inclusion in society—including equitable education, affordable housing and access to jobs—seeking a fundamental reformation of society and its institutions. However, the challenges Dr. King battled in Chicago decades ago still plague us, from school inequality and segregation to lack of access to quality affordable housing.

The inequities that Dr. King battled persist in our region today, in part, because they’re enabled by a form of governance that feels innocuous: local control. But local control means smaller units of government make unilateral decisions, from school boards to aldermen.

The inequities that Dr. King battled persist in our region today, in part, because they’re enabled by a model of governance that feels innocuous: local control.

Local control in policy making is not inherently bad. At its best, policy proposals that seek beneficial results for the entire city are refined to include local concerns and add local value. At its worst, local control creates or reinforces discriminatory practices that burden marginalized communities of color and benefit wealthy and often white communities. Administrative law and rulemaking has long been used as a method to reinforce segregation. In the 1960's, Chicago Public Schools (CPS) used attendance boundaries to keep schools racially segregated. Superintendent of CPS, Benjamin Willis, described the policy not as segregation, but as neighborhood school preservation, consistent with Chicago’s history of deference to local control. It is also a prime example of how northern cities achieved Jim Crow results without explicit Jim Crow policies.

In plain language, this privileging of ‘local preference’ in decision making results in racial and economic exclusion.

Chicago’s activism around the issue caught the eye of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. He visited Chicago organizers prior to the ‘63 boycott, for which over 200,000 students did not attend school and over 20,000 marched in protest Chicago’s school segregation on what became known as ‘Freedom Day’. Though no policy change occurred in response, the event did inspire The Chicago Freedom Movement and the later involvement of Dr. King in Chicago.

Today administrative rulemaking takes the form of school closing due to low enrollment and the shifting of enrollment boundaries to give higher-income residents access to resources at the expense of communities of color. In the 2018-2019 school year, CPS changed its rules to allow for community members to request a school closing as the only justification needed to initiate a school action. This justification was used to request that National Teachers Academy, a majority black majority low-income school, be closed and converted to a high school. The school maintained adequate enrollment and was performing at level 1+, the highest designation possible under the CPS rating system. There was no academic justification to close the school, yet influential local residents pushed for prioritization of their desire for a high school over the needs of majority low-income black and brown students—and they almost succeeded. Ultimately, in December 2018, the decision was blocked by the court and CPS decided not to appeal.

Administrative law and rulemaking has long been used as a method to reinforce segregation.

Another method for reinforcing discrimination is in the power held by politicians to prevent inclusive change from occurring. Dr. King returned to Chicago to help lead the Chicago Freedom Movement in 1966 advocating for the end of slums which included open housing, quality education, transportation and job access, income and employment, health, crime and the criminal justice system, community development, tenants’ rights and quality of life. Dr. King chose Chicago after the ‘63 boycott because “the atmosphere was created last summer for the building of a vibrant movement to end discrimination, injustice, slums and slumism in the City of Chicago” and felt if demonstrations made progress in Chicago, they could be successful anywhere. Unfortunately, Dr. King would face resistance previously unseen.

Local neighborhood resistance was fierce in opposition to the Chicago Freedom Movement and Dr. King. He was famously hit in the face by a rock while marching through Marquette Park protesting housing discrimination and slum conditions. The movement faced a new, specific defiance in the form of Chicago local control, where neighborhood disapproval and violence came directly from the then majority white community. “I have seen many demonstrations in the south but I have never seen anything so hostile and so hateful as I’ve seen here today”, Dr. King is quoted as saying. Instead of challenging the hostility of the residents, Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley filed an injunction to limit the size and duration of marches.

Today administrative rulemaking takes the form of school closing due to low enrollment and the shifting of enrollment boundaries to give higher-income residents access to resources at the expense of communities of color.

The stakes rose when Dr. King pursued a march in Cicero, site of a race riot in 1951 after Harvey E. Clark, and African-American man, rented an apartment in the Chicago suburb. Due to its history, a march in Cicero was considered to be suicidal. Chicago Mayor Richard J. Daley pushed an agreement in which CHA would build low rise housing and that loans would be accessible to all races through the Mortgage Bankers Association. The agreement resulted in unkept promises, and in true Chicago fashion, activists decided to march anyway. Though many view this agreement as a hollow victory, it paved the way for passage of Fair Housing Act of 1968 after Dr. King’s assassination.

Today, Aldermen control zoning changes in their wards with little oversight as to the merits of their decisions allowing them to unilaterally block development. Opponents of affordable housing use local-control to impede housing proposals, often described as NIMBYism, to protect a racially homogenous status quo. As my colleague Marisa Novara has previously noted, “[o]ur practice of deferring to local decision-makers (on) matters that should be city-wide policy has a similar impact as previously more overtly discriminatory practices such as redlining and restrictive covenants.”

Today, Aldermen control zoning changes in their wards with little oversight as to the merits of their decisions allowing them to unilaterally block development. Opponents of affordable housing use local-control to impede housing proposals, often described as NIMBYism, to protect a racially homogenous status quo.

In plain language, this privileging of ‘local preference’ in decision making results in racial and economic exclusion. Aldermanic prerogative and administrative rulemaking are two ways Chicago perpetuates the exclusion of low-income, primarily persons of color from majority white, higher-income communities. It is imperative that policy and process limit institutional local control when it excludes low-income and minority residents from accessing public services and restricts neighborhood inclusion. Limiting exclusionary local control practices would increase decision transparency and be inclusive of all members of a community.

Though he was in Chicago for a brief time, Dr. King’s legacy through housing advocacy is felt today. His work in Chicago has been memorialized by a Marquette Park memorial, the same place he was struck with the rock. There are affordable housing units at the site of Dr. King’s apartment in North Lawndale. Stone Temple Baptist Church where he preached during his time here was given landmark status in 2016. These landmarks serve as reminders of the struggle taken to address exclusionary local control, whether it is administrative rulemaking, aldermanic prerogative or other methods. As we remember the work of Dr. King in Chicago, let us channel his spirit for a more equitable and inclusive city. Chicago can do better.

Learn more about Chicago's '63 Boycott, in which over 200,000 students boycotted school. The event inpsired Dr. King's later involvement in Chicago:

"From the '63 Boycott to #SaveOurSchools" by Gabriel Charles Tyler

MPC’s Blogs and Data Points on community development and equity issues such as this are made possible in part by the Chicago Community Trust – Seale Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Field Foundation of Illinois, the Bowman Lingle Charitable Trust, the Conant Family Foundation, and individual donors.