Earlier this week the City of Chicago elected the first African American woman in its history to serve as mayor. It is a watershed moment to celebrate—congratulations to Mayor-elect Lightfoot. While moving expeditiously into transition tasks, the challenges ahead are daunting: rising debt, violence, police reform, affordable housing, school performance, job growth, and many more. All of these issues are inextricably linked to addressing our history of segregation and inequality, and creating pathways to opportunity for residents of South and West Side communities. Structural racism and segregation are often discussed but seldom addressed in a bold and comprehensive manner. Now is the time to make equity the top priority of the new administration. Our city’s viability lies in its ability to make progress on our inequitable past.

Chicago Cannot be a Vibrant City if it Keeps Losing its Black Residents

Chicago’s black population has been declining for over two decades. The number currently stands at roughly 800,000, down from approximately 1 million in 2000, a fact that MPC and many others have noted. Largely because of this, Chicago’s total population has been flat for the past several years, while the greater Chicago region has actually lost population. Population loss eats away at our ability to raise the revenue needed to address Chicago’s budget challenges. But more importantly, can we really consider Chicago to be a vibrant, livable, equitable city if one of its largest population groups is fleeing?

The challenges ahead are daunting: rising debt, violence, police reform, affordable housing, school performance, job growth, and many more. All of these issues are inextricably linked to addressing our history of segregation and inequality...

There is no clear answer to why black families are leaving Chicago, but data hint at a reverse migration, with southern cities being the recipients of black families who have left Chicago. Pete Saunders identifies “displacement through disinvestment” as a likely cause. Opportunities for economic mobility are tightly tied to place, and in many predominantly black neighborhoods, employment options and new investments are scarce. Saunders notes that 60% of black residents who have moved from Chicago did not have a job when they moved. They may have simply been seeking other areas, outside of deeply segregated Chicago, where there are greater opportunities for employment and quality of life.

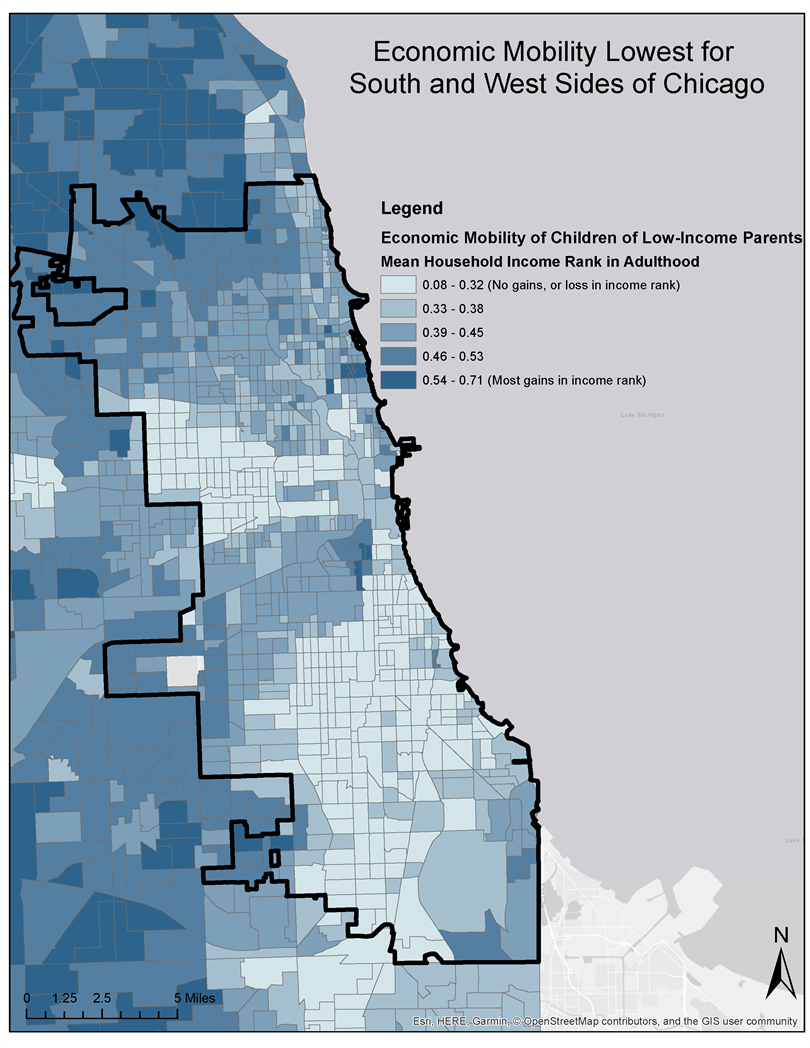

Economic Opportunity is Tied to Place, and Those Places are Largely White

Last year, Harvard economist Raj Chetty and collaborators at Opportunity Insights released data and interactive maps illustrating just how strongly earnings, economic mobility, and other outcomes associated with place. Lifetime earnings, educational attainment, and employment outcomes for those living in “opportunity areas” are much greater. These areas are predominantly white, and in Chicago, largely on the north side. As the map below indicates, west and south side children born low-income families experience the least amount of income gains by adulthood.

Data obtained from Opportunity Insights

These geographic desparities are no coincidence. They are directly tied to the racist, inequitable legacy of past policies. If one overlays the original “redline” maps from the Federal Home Owner’s Loan Corporation (HOLC), as the National Community Reinvestment Coalition did last year, the pattern is immediately clear. The neighborhoods that were refused loans for home purchases, a practice banned by the Fair Housing Act in 1968, are the same ones identified as having low economic mobility today. Black families have long been locked out of predominantly white communities, while witnessing little of the investment that has transformed much of the rest of the city and helped white families accumulate wealth.

Breaking Down Mobility Barriers is a First Step

Ever since the Gatreaux lawsuit in 1966, when the Chicago Housing Authority was challenged for racial discrimination in its housing locations, policymakers have been working toward pathways for low-income residents to access more racially and economically mixed areas. Experimental studies from the federal Moving to Opportunity program, and work by Professor Raj Chetty and others have shown that outcomes such as lifetime earnings and educational attainment are higher for people when they can access higher-opportunity areas. But there are few affordable housing options in such areas. MPC’s Shehara Waas illustrated that communities on the south and west sides have the largest share of affordable units, while many north, northwest, and southwest side communities have a nearly nonexistent—less than 5%—share of affordable units.

Predominantly white communities, and particularly those with high rates of homeownership and higher property values, often fight the creation of new affordable housing. Opponents of affordable housing rarely mention race, but it is always lurking, thinly veiled, behind each argument. Aldermen use prerogative to scuttle proposed developments. A first order of business for our new mayor-elect is injecting sunshine and abolishing the use of aldermanic prerogative to block affordable housing developments. This would open up racially and economically mixed neighborhoods for low-income black and brown residents. Providing pathways to opportunity through mobility is an important step, but our new mayor-elect must also equally prioritize place-based investments.

Ending the Punishment and Disinvestment of Black and Brown Communities is Just as Important

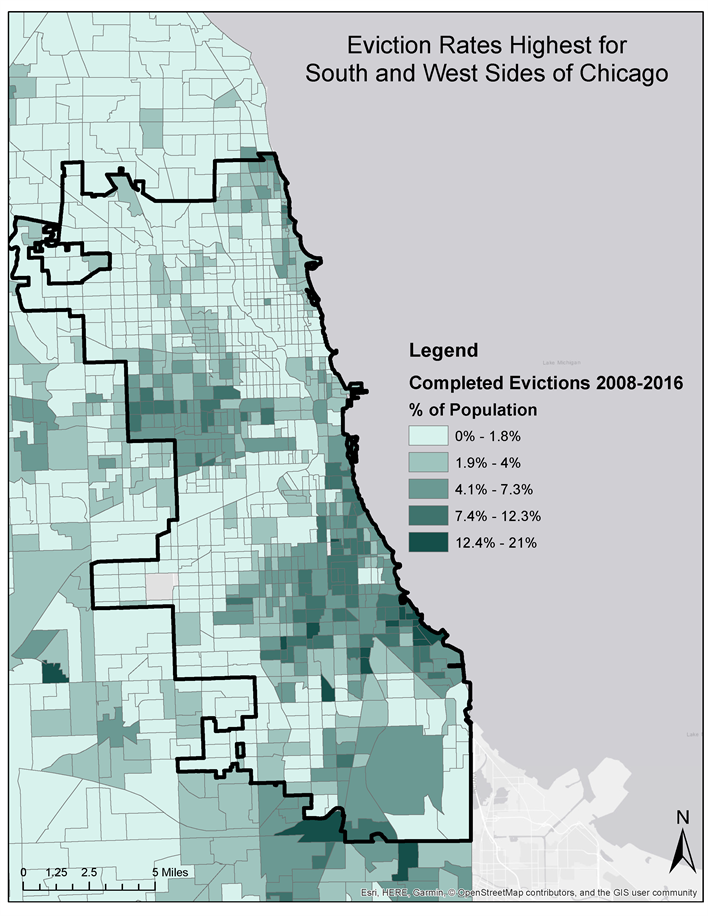

Mobility is a part of the urban experience, but it is experienced much differently for black families. Poor people are often pushed out and forced to move, and then have limited housing options. Low-income white families are more likely to have children who grow up in the same census tract as their parents, and more likely to live in areas with upward economic mobility, than low-income black families. Low-income black families are much more likely to move, but are not necessarily reaping any economic benefits. The map below illustrates how forced mobility through eviction is disproportionately experienced on the south and west sides.

Data obtained from Eviction Labs

For decades, Chicago has displaced black families not just through disinvestment, but also through punishment. The large sums of public dollars spent on policing and incarceration have also contributed to the uprooting of black and brown families. Policy levers have unfortunately made the black and brown neighborhood experience a punitive one—foreclosures, evictions, incarceration, public housing redevelopment, school closures, and mental health clinic closures—all have contributed to physical mobility while blocking economic mobility. The maps below indicate the large percentage of low-income children who have had a parent locked up in jail or prison. In some areas of Chicago’s south and west side communities, it is nearly 20%.

Data obtained from Opportunity Insights

In addition, the Chicago Housing Authority’s Plan for Transformation displaced many black families from areas that have witnessed large income and economic mobility gains. For decades, our policies have displaced black families, leaving them to chase the fleeting possibility of accessing whiter or more integrated spaces. Neighborhoods where public housing once stood and black families once lived—such as Cabrini Green, Lathrop Homes, and ABLA—have witnessed rising incomes and property values. Places aren’t static, but high opportunity, white neighborhoods seem to be magnetically resistant to people of color.

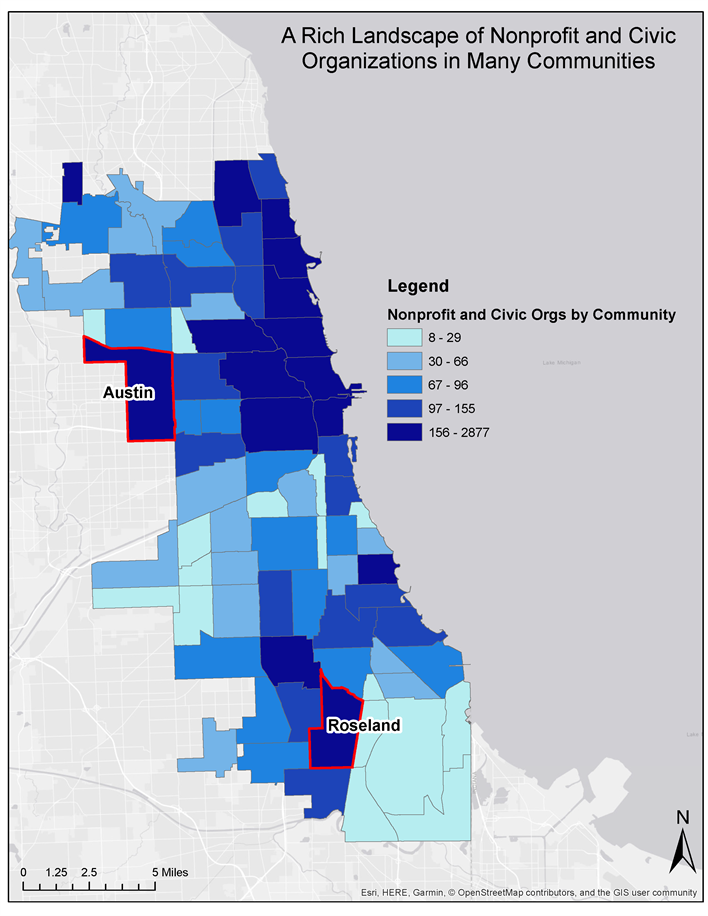

The Right to Place and the Importance of Community

We need policies that strongly assert both the right to access opportunity through mobility and the right to access opportunity through place—that is, the option to stay rooted in one’s neighborhood and reap the benefits of investments in people and institutions. We have become conditioned to view neighborhoods as dichotomous—good or bad—and this predictably aligns with notions of race. White neighborhoods are viewed as good and black neighborhoods bad. But static maps never tell the whole story about what constitutes a neighborhood and community. Interactive data presented on Opportunity Insights' website show that despite segregation and entrenched challenges, neighborhoods of color are capable of producing good outcomes for young people and families. For example, in many of the lowest income black families, the unemployment rate is higher than the median for all of the lowest income families. However, there are many neighborhoods—in South Austin and Roseland, for example—where the unemployment rate for low-income black families is actually quite low.

From this, we can glean that there are many features of a place, or neighborhood that contribute to its residents’ quality of life. The social, civic, and institutional infrastructure of a neighborhood is what builds community, provides networks for residents to plug into, and social capital to advance the well-being of families. The neighborhoods referenced above are rich in non-profit organizations working to improve and build community, as the map below illustrates.

Mayor-elect Lightfoot must build on this existing civic infrastructure, and work collaboratively to end punitive policies and attract new investments that will benefit longtime residents. We need a coordinated plan to build resilient communities, where residents will have a pathway to economic mobility in the place they currently live. Residents don’t need another description of what’s wrong with their community, they need solutions that leverage the many existing assets, and equitably prioritize pathways to opportunity. Such a plan that places equity first, will help stem the tide of black population loss in our city.

Promising Solutions for an Equitable City of Chicago

MPC outlined promising policies that can help build a more equitable Chicago that can be found here. In addition, the following solutions could prioritize place-based investments in the south and west sides of the city:

- Help end aldermanic prerogative immediately

- Reform TIF so that money actually goes to areas that have long been starved of investment

- Enact Community Benefits Agreements that prioritize the hiring of people from south and west side neighborhoods

- Enact better tenant protections

- Make housing more easily accessible to individuals with a criminal record

- Work to attract new investments into opportunity zones

- Expand the Equitable Community Schools pilot program so that west and south side schools remain civic pillars of the community

- Work with residents on new master plans that encourage development and improvements that residents want

- Invest in the civic and social infrastructure—organizations that tie community together

MPC’s Blogs and Data Points on community development and equity issues such as this are made possible in part by the Chicago Community Trust – Seale Fund, the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Field Foundation of Illinois, the Bowman Lingle Charitable Trust, the Conant Family Foundation, and individual donors.