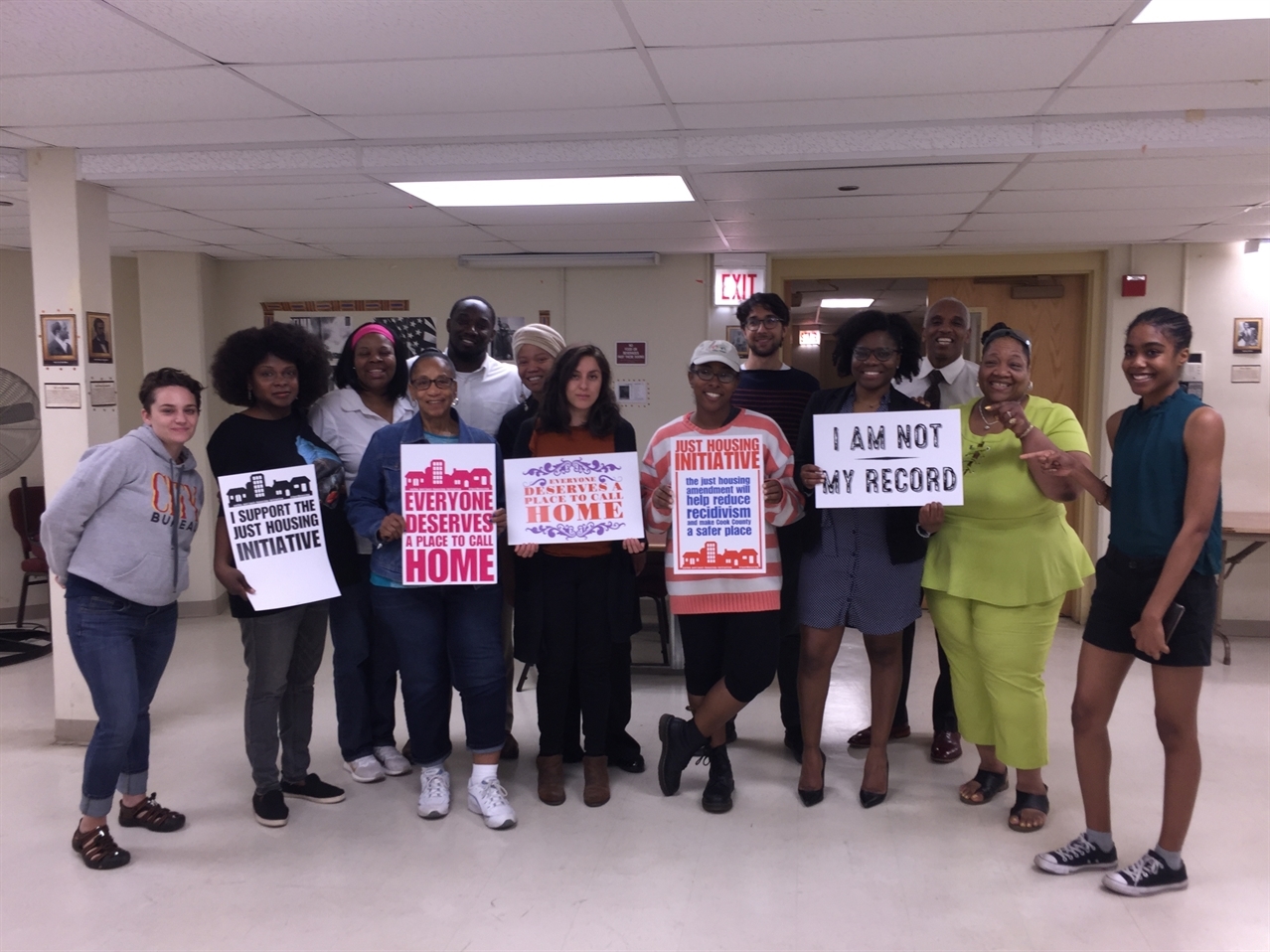

The Just Housing Initiative Coalition prepares for the April 24th hearing

By Patricia Fron, Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, and Marie Claire Tran-Leung, Shriver Center on Poverty Law

By Patricia Fron, Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance, and Marie Claire Tran-Leung, Shriver Center on Poverty Law - April 23, 2019

Note: On Thursday, April 24, The Cook County Board of Commissioners passed the Just Housing Amendment which ensures that people with arrest and certain conviction records will have a fair chance to apply for housing throughout Cook County.

Everyone in favor of criminal justice reform, regardless of your political leaning or underlying motivations, must be willing to make changes and challenge ourselves. We must take a moment to look beyond policing, sentencing, and what happens within jail and prison walls to how we, as a society, treat individuals who have had interactions with the criminal justice system. This means that it is not just our legislators, police, and judges who must take on the charge of change; we all have work to do, and we must commit to checking our own mindsets and prejudices about who deserves to live and work in our communities and be our neighbors.

One in three U.S. adults has some type of arrest or conviction record.

One in three U.S. adults has some type of arrest or conviction record; by comparison, arrest or conviction records are more common than four-year college degrees in the U.S.[1] In Cook County, this equates to more than 1 million residents. With quick and inexpensive access to these records, the effects of having an arrest and or conviction can be severe—individuals with records are marked, and often marked for life. Even a simple arrest or very old conviction can and often does deter an employer from hiring and a landlord from renting.

Take the example of Troy: As a veteran and a leader in his South Suburban community, Troy exemplifies the ideal of serving others. And yet, he too was limited in his ability to get housing long after serving his time behind bars. To overcome the drug addiction that he developed after Desert Storm and that led him to steal from a former employer, Troy underwent rehab and later excelled at his job helping hundreds of chronically unemployed people re-enter the full-time workforce. Nevertheless, Troy’s record created a formidable barrier to renting a home for his family. The unfairness and universality of his situation were not lost on Troy, who explained: “It takes only a second to break the law but a lifetime to live with the consequences. One second, one crime, one serious lack of judgment . . . in America this can be a life sentence.”

Arrest or conviction records are more common than four-year college degrees in the U.S.

As is the case for countless others, Troy had to struggle for a second chance. Assuming justice were blind, this would still be unfair. But it’s not; many people barely get a first chance. Grave inequities within the criminal justice system based on race, ethnicity, and disability, when combined with deeply rooted residential segregation reinforced by housing discrimination, tips the scales of justice overwhelmingly against a great number of Americans. Black and Latinx communities, and people with disabilities are more likely to be arrested, and those arrests are followed by more stringent sentencing. Even after they serve out those sentences, they are more likely to have their record used against them when searching for housing.[2] And this impacts not only the individual with the record, but entire families as well. Nearly two-thirds of people in Illinois prisons who have minor children.[3]

Stella is one of those parents. Upon her release in 2017, she longed to provide stability for the child she had been separated from, particularly to minimize the type of instability and trauma she had experienced during her childhood as a ward of the state. Her conviction history, however, has resulted in countless denials from landlords, which persisted even after she started working with a service provider and obtained a housing subsidy. Landlords willing to accept her with a record tend to have units that are in disrepair or in neighborhoods that lack the opportunity she seeks for her child, thus depriving her of any real housing options. The longer she goes without housing, the longer her child must remain in the care of others and away from her mother. Stella has recognized that “housing is the foundation for building families,” and yet, the building blocks she so critically needs are out of reach due to her record.

By adopting a new proposal—the Just Housing Amendment to the Cook County Human Rights Ordinance—the Cook County Board of Commissioners can help end this life sentence and ensure a fair chance at housing for Troy, Stella, and others like them living in the county with an arrest or conviction record. Introduced by chief sponsor Commissioner Brandon Johnson and co-sponsors Commissioners Larry Suffredin and Jeffrey Tobolski, in partnership with the Just Housing Coalition—a group of 115 supporter and coalition member organizations, the Just Housing Amendment aims to reduce unfair housing discrimination against justice-involved individuals by limiting the types of criminal history that landlords can consider, such as arrests, juvenile records and expunged/sealed records. As for convictions, housing providers would be required to conduct an individualized assessment and consider factors such as the nature of the offense and how long ago it occurred. The amendment also aims to add transparency to the tenant screening process.

With the Just Housing amendment in place, fathers like Troy will have a chance to show that they are more than their past mistake instead of being greeted with a criminal history question that sends the message, “You are not welcome here.” Mothers like Stella will have a fair opportunity to reunited with families. And Cook County will get serious about holistic criminal justice reform and work to ensure that people with records, like everyone else, have a place to call home.

Patricia Fron is executive director of the Chicago Area Fair Housing Alliance. Marie Claire Tran-Leung is an attorney at the Sargent Shriver National Center on Poverty Law and Soros Justice Fellow.

[1] The Sentencing Project. “Americans with Criminal Records.”

[2] http://www.gnofairhousing.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/09/Criminal_Background_Audit_FINAL.pdf; https://equalrightscenter.org/press-releases/unlocking-discrimination/

[3] https://cdn.americanprogress.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/12/09060720/CriminalRecords-report2.pdf