MPC

By Christina Harris and and Olga Bautista, Alliance for the Great Lakes

By Christina Harris and and Olga Bautista, Alliance for the Great Lakes - June 1, 2021

An environmental justice collaborative in Southeast Chicago spent two years studying the lasting health impacts of industry in their community. Lens on the Calumet Corridor: A blog series highlighting the research in the Calumet Connect Data Book captures what they discovered, and why it’s time for a change. This is the second blog in our six-part series.

When it comes to environmental racism, Illinois has earned a dubious title. A University of Minnesota study ranked the Land of Lincoln third in the nation when it comes to pollution gaps (1), racial equities related to pollution exposure. While low-income individuals, young children, and adults of color are disproportionately exposed to residential pollution state-wide, this inequity is more pronounced in the City of Chicago, where COVID-19, the Hilco Crawford plant explosion, and the proposed relocation of General Iron have further proven the need for systemic changes to policies around land use and demolitions.

One method to combat environmental racism in our region may surprise you: modernizing policies around our industrial corridors. In Chicago there are 26 industrial corridors, many of which have a legacy of pollution with land uses that are now outdated and do not fit neighborhood and community context.

Chicago’s industrial corridors are an important asset. Located throughout the city, the corridors are used for industrial and manufacturing activities, providing jobs that are often higher paying than those in other sectors, like retail. Within these corridors, facilities specializing in chemical manufacturing, motor vehicle manufacturing, waste management, and chemical wholesale trade, among other things, carry out their day-to-day operations.

Industry and environmental racism grew up alongside each other

Industrial corridors historically sprang up along waterways and rail lines for access to transportation networks and waste disposal into the river. When many industrial uses first started there was little concern about how these facilities’ outputs (hazardous/non-hazardous waste disposal and emissions) were impacting the environment and surrounding communities. Although Chicago-based activists had long been organizing around environmental justice, when concerns around a toxic waste landfill in Warren County, NC gained national prominence in the 1960’s, local momentum was able to build in an unprecedented way. The protest in Warren County—a poor and predominantly Black area—premised under environmental injustices (2) being faced by communities of color ignited Chicago organizing, where zoning codes and land-use laws enforced segregation and resulted in low-income, minority communities as host sites for industrial facilities with known negative environmental impacts.

Industrial corridor modernization initiative promises a less polluted path forward

According to the City of Chicago’s Department of Planning and Development (DPD), manufacturing is among the region’s largest and most prominent sectors. The City’s industrial land use policies, which have not been updated in approximately 25 years, formally designated these areas as industrial corridors in 1992 via the Chicago Plan Commission, restricting the corridors’ zoning and uses to primarily industrial or manufacturing activities.

In 2016, the Department of Planning and Development launched the Industrial Corridor Modernization Initiative, which aims to “unleash the potential of select industrial areas for advanced manufacturing and technology-oriented jobs while reinforcing industrial activities in other areas; maintain and improve the freight and public transportation systems that serve industrial users in key job centers; support new job growth and local job opportunities, including residents in “at risk” communities; and leverage the unique, physical features of local industrial corridors to improve viability and foster demand.”

Recent modernization efforts have not served communities most impacted by environmental racism

Despite the City acknowledging the need for policy reform and specifically naming “at risk” communities as a priority for the modernization initiative, modernization efforts first began along the North Branch of the Chicago river, in a corridor situated between two relatively affluent Chicago neighborhoods. Prior to and as planning began, many community members and residents noted that the North Branch Corridor was selected first due to the commercial interest in redeveloping the corridor’s prime real estate, ripe for retail and residential properties.

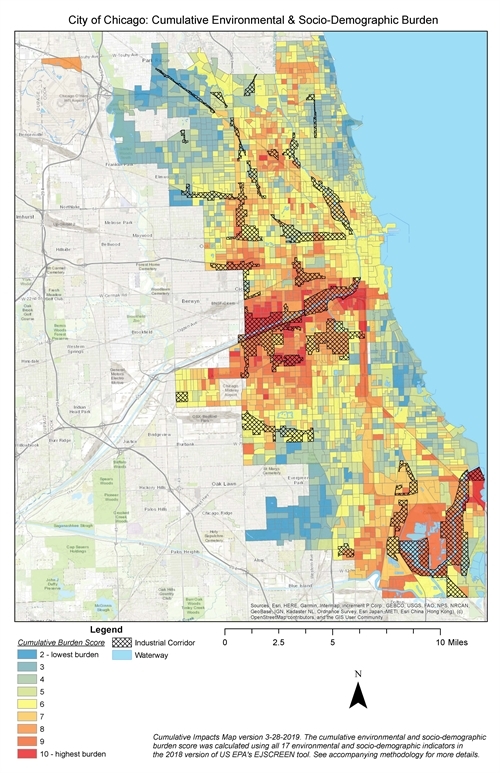

To live up to the stated goal of supporting job growth and opportunities in “at risk” communities, the City process should have selected corridors located in or adjacent to neighborhoods that are low-income and underserved by employment. Many of these corridors are located in the south and southwest areas of the city. These same corridors have also been identified as having greater cumulative environmental and socio-demographic burdens as demonstrated by mapping analysis released by the Natural Resources Defense Council (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Cumulative Burden of Environmental Exposures & Population Vulnerability in Chicago. Mapping analysis created by the Natural Resources Defense Council.

There are high cumulative burdens of environmental pollution located in many environmental justice communities across Chicago and supports the need for land use and public health reforms, most urgently in industrial corridors located in the southwest and far south.

Calumet Industrial Corridor Modernization Initiative

As indicated by the Department of Planning and Development, the southeast side of Chicago, which is home to the Calumet Industrial Corridor, is one of the corridors next in line to undergo the land use modernization process. Data from 2017 indicates that an Hispanic/Latinx population makes up more than half of the study area population, 58.96 percent, followed by Black/African-American residents at 25.02 percent. This demographic is notable, considering that environmental justice communities, in most cases, tend to be made up of residents of color, as is the case with our study area.

Zoning and planning ordinances have typically not been created with public health and the environment in mind. They are typically framed around the need for economic development and jobs rather than an approach that integrates and prioritizes health and community needs. These land use planning and policy decisions have set-up a false binary, pitting economic development against environmental and public health, rather than championing a co-existence.

Previous modernization efforts that have been conducted in the North Branch, Ravenswood, Kinzie and Little Village Corridors have been varied without a consistent process for engaging communities and stakeholders. The City should integrate a more equity-centered and community-driven decision making approach such as the one set forth by the Great Cities Institute (GCI) Calumet River Communities Planning Framework. As planning continues, we want to advocate for these types of frameworks to be followed so that community residents can be true partners in creating new land use visions for their neighborhoods.

Want to get Involved?

http://setaskforce.org/

https://www.claretianassociates.org/

Former MPC Resarch Assistant Chloe Nunez contributed to this post.

(1) Pollution Gap was coined by Lara P. Clark, Dylan B. Millet, Julian D. Marshall in their article titled, National Patterns in Environmental Injustice and Inequality: Outdoor NO2 Air Pollution in the United States meaning that there are racial inequities that exist when it comes to pollution exposure.

(2) Environmental justice, as defined by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), is the “fair treatment and meaningful involvement of all people regardless of race, color, national origin, or income, with respect to the development, implementation, and enforcement of environmental laws, regulations, and policies.”