Flickr user clarkmaxwell (cc).

We could see more Metra trains on the line with a broadened sales tax.

Published monthly, MPC’s Talking Transit provides updates about transit-related activities around the world.

Get In the Loop on all the latest local, national and international transit headlines.

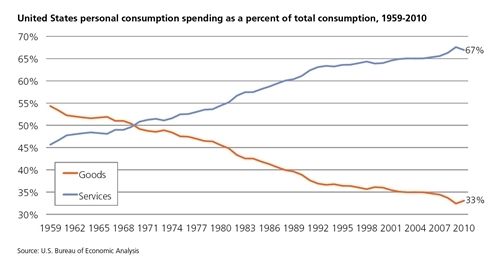

Did You Know? In the 1950s, Americans devoted over half of their personal spending to material goods, from cars to refrigerators to the new Barbie doll. The growth of the economy over the past half-century has not reduced the consumption of household goods, but the share of spending devoted to such needs has declined dramatically, to just a third of total personal spending by 2010. On the other hand, services from lawn care to hairdressing now collectively account for two-thirds of spending.

Our tax system is outmoded—and we’re paying the price in transportation

Our local transit systems rely heavily on the sales tax. A large majority of funding for Chicago Transit Authority and Metra commuter rail operations are derived from a sales tax in the six-county Northeastern Illinois region. Those revenues are vital to keeping our trains and buses moving, as passenger fares only contribute about half of the total cost of operations—let alone new capital expenses. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC), which supports the vital provision of transit services in the region, is working to support long-term, reliable funding for them.

Illinois has one of the narrowest sales tax bases in the country: Only 17 of 168 potential taxable services are included, ignoring most of the economy. This narrow base hampers investment in the region’s growing demand for transit.In Cook County, for example, sales tax revenues—when adjusted for inflation—have only increased by 10 percent since 2000, at the same growth rate as ridership on the CTA.

But that growth was only possible because the State of Illinois passed a significant sales tax increase in 2008 that augmented the devoted tax to regional transit from 1 to 1.25 percent in Cook County and 0.25 to 0.5 percent in the five collar counties. Had the tax remained at the previous rate, total sales tax revenues in the region would have actually declined by 11 percent when adjusted for inflation, as shown in the following table. Because the Illinois sales tax is so narrow, we’re getting less and less return on the dollar, and transit agencies are suffering from the consequences.

Transit wins by broadening the sales tax base

By updating the tax law to include personal services, the state would be adopting a more stable source of revenues. And while we already have one of the highest sales tax rates in the country—totaling 9.25 cents on the dollar in the city of Chicago— the increase in revenues at the state level would be enough to reduce the state sales tax rate by a full percentage point while breaking even.

Surrounding states like Iowa, Missouri and Wisconsin already tax a number of their services, so Illinois would not be all alone on this issue.

It’s a proposal that has made it onto the campaign platforms of prominent Illinois and Chicago politicians, and received endorsement from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning.

But perhaps the biggest winner from a sales tax increase would be the Chicago region’s transit agencies, which would stand to gain almost $100 million collectively on an annual basis in the first year, with that amount likely growing with time. If distributed to the regional transit agencies like Chicago Transit Authority and Metra at a rate similar to today’s, those funds would increase agency budgets by 3 to 5 percent, adding more than $40 million for the Chicago Transit Authority, $30 million for Metra and $20 million for Pace bus and paratransit services. Those funds would go a long way toward improving daily service on train and bus lines throughout the region, adding service on some lines and potentially restoring service on others.

MPC supports exploring alternative funding sources in an era when states and municipalities can’t rely upon scarce federal dollars. Transportation funding on maintenance and capital projects can’t wait—and shouldn’t have to—for a time in the future when funding is plentiful again.