Flickr user Stuart

Chicago's GINI coefficient for inequality, referenced below, is the same as El Salvador's.

By Breann Gala and MPC Research Assistant Nora Taplin

By Breann Gala and MPC Research Assistant Nora Taplin - September 16, 2014

In his recent best-seller, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, French economist Thomas Piketty argues that in our current state of inequality, “The past devours the future.” In other words, when the private rate of return on capital (or wealth) that has already accumulated becomes greater than the wages and other outputs from current business activities, the result is that the rich become ever richer while the rest of society doesn’t have the opportunity to catch up. This equation is at the root of the growing inequality in the U.S. and around the world today. While economic inequality is a global problem, it creates specific challenges in the Chicago region. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) addresses these challenges through our housing, transportation and community development advocacy and initiatives.

I can’t remember ever seeing an economics book top the Amazon and New York Times best-sellers lists. But Piketty’s research is revolutionary and his arguments clearly lay out why growing inequality is an issue that impacts all of us. Ideally, economic growth rewards entrepreneurs and workers for the efforts that they put into the economy. This kind of growth encourages new businesses and allows individuals and families to move up the economic ladder. Piketty demonstrates with his historical data that under normal conditions, economic growth rarely exceeds 1 to 1.5 percent. The only places that have had sustained economic growth of 3 to 4 percent are developing countries, places that are actively catching up to the levels of technology in the most advanced societies (a status that is by definition time-limited). Much of Western Europe fell into this category from 1950 to 1970, when these nations were recovering from World War II.

On the other hand, the pure rate of return on capital (which in rich countries today consists mostly of financial and real estate assets) does average around 3 to 4 percent and is fairly stable over time. Historically, the rate of return on capital has shown a tendency to exceed the rate of economic growth, inevitably leading to the concentration of wealth. When growth from new business activity and labor is completely overwhelmed by the growth of wealth, inequality spirals out of control and wealth becomes increasingly concentrated in the hands of a few families. Furthermore, your economic fate is determined increasingly not by your own achievements, but by inheritance.

To make this argument, Piketty uses extensive income tax return data spanning 20 countries, including the U.S., Canada, Germany, Japan and India. The data goes back to 1910 for most countries and as early as the 1880s for some. In addition to looking at incomes, Piketty also uses estate tax return data in order to examine how inequality of wealth has changed over time. The estate tax data is available for fewer countries, but in some cases goes all the way back to the beginning of the 19th century. This extensive historical data allows Piketty to put the trials of our own time into perspective.

Piketty finds that there was a massive reduction in economic inequality from 1910 to 1950 in most developed countries and this reduction was due to the economic shocks of the two world wars and the policies adopted to absorb those shocks. Since 1980 income inequality has risen dramatically in the U.S., and if this increase continues at its current pace, the top 10 percent of the income distribution will be earning 60 percent of national income by 2030. Wealth inequality (or the inequality of assets) is even greater, with the top 10 percent of the wealth distribution holding more than 70 percent of all wealth in 2010. Piketty argues that we must change our fiscal policy in order to protect the ability of those who were not born wealthy to participate in the economic future. He recommends a global tax on wealth to check the growth of economic inequality.

Chicago is not at all immune to the problem of economic inequality. According to a variety of measures, this is a serious problem for Chicago and the region: Chicago’s inequality measure is the same as El Salvador, a country struggling with social instability, concentrated wealth, violence challenges and low skill levels. According to a Brookings Institution report, another measure of income inequality, the 95/20 ratio (which measures the disparity between the top 5 percent of income earners and the bottom 20 percent), indicates that Chicago is one of the 10 most unequal cities in the U.S.

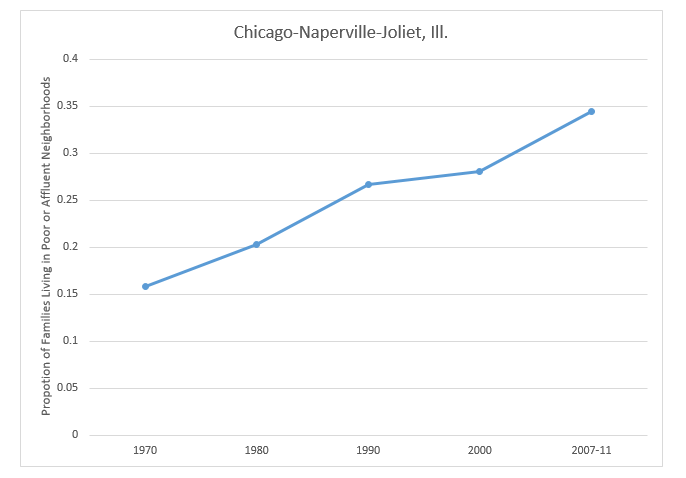

New analysis shows that residential income segregation is on the rise in Chicago. The proportion of families living in poor neighborhoods (where median income is less than two-thirds of the metropolitan area median income, which was $75,475 according to the 2007-2011 American Community Survey) or affluent neighborhoods (where the median income is more than one-and-a-half times the metropolitan area median income) has increased steadily since 1970.

This graph suggests the middle class is shrinking, as an increasing proportion of families are living in either poor or affluent neighborhoods.

Data from US2010

MPC’s current equity agenda is focused on expanding housing opportunities in low-poverty, opportunity communities through the Regional Housing Initiative and Voucher Pilot and on building municipal capacity to address the suburbanization of poverty and housing market instabilities. Through research and demonstration pilots, we’re interested in building off the national literature, like Piketty’s groundbreaking work, to explore how rising inequality is unfolding in Chicago and what this trend is costing us all. Often the inequality debate focuses on the extremes—concentrated wealth and concentrated poverty. To effect real change, we must explore the cyclical nature of inequality and its impact on governments, neighborhoods and the middle class.