flickr: Nic McPhee

Just another work day in Minneapolis

This post is the second in a series of three. Read the other two.

We last looked at Census data that showed that of the top 20 most populated regions in the U.S., Chicago ranked 18th in population growth. From 2010 to 2013 it grew by just about 20,000 people annually, about 0.22 percent a year, substantially less than most peer regions across the country. That matters because if Chicagoland grew at the average rate of the top 20 metros, we’d gain, for example, $271 million in state and local tax revenues and $4.2 billion in personal income annually.

A Midwest comparison

It’s not just the coasts or warm weather areas that are growing faster than the Chicago region. Midwestern counterparts are outpacing us too. From 2010 to 2013, the Minneapolis region’s population grew more than three times faster than the Chicago region, and the city of Minneapolis almost five times faster than the city of Chicago.

In 2013, Minneapolis Mayor R.T. Rybak set a high goal that the city grow to 500,000 people over the next 10 years, a 22 percent increase. His reason? “The more people there are to support strong schools, shopping districts, restaurants, art groups” and other amenities, adding, “More people living in Minneapolis means that more of us share the costs of running a city.”

The Urban Institute’s Mapping America’s Future tool predicts that the goal is certainly achievable. Over the next 15 years, it forecasts that region-wide, Minneapolis will grow by more than 20 percent, or 640,000 people. That same tool forecasts the Chicago region to grow by only 7.5 percent during the same period.

What’s going on in Minneapolis? It’s certainly not the weather.

Jobs and economic growth

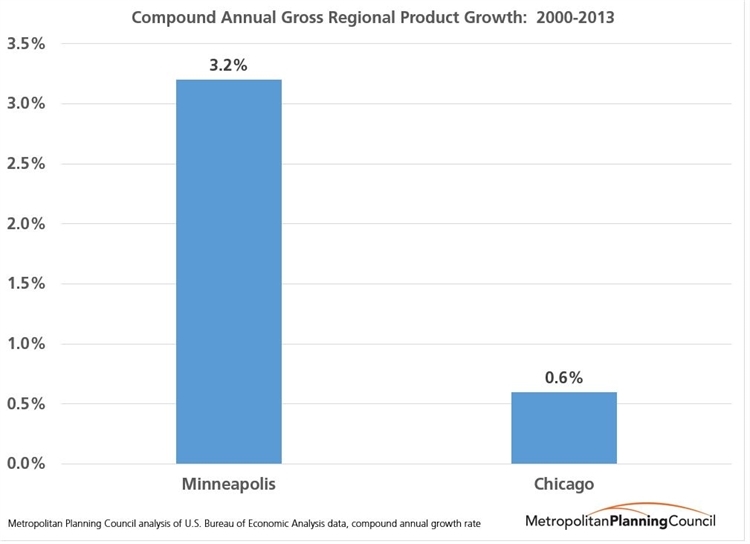

After analyzing a host of indicators and trends, the key difference between Chicago and Minneapolis is that the city to our north has maintained a strong economy, far outpacing Chicago and other cities throughout the nation, even during the recession.

For starters, 33 of the nation’s largest 1,000 firms are located in Minneapolis. Thirty-three! While 62 of these firms are located in Chicago, we’re a city eight times Minneapolis’ size.

And while the number of private-sector jobs in the Chicago Loop now stands at nearly 542,000, the highest since 1991, and the City ranks number nine On The Economist’s list of cities that will be the most economically powerful in the world by 2025, Chicago’s unemployment rate has been a sticking point. It has remained consistently high compared nationally and especially to Minneapolis.

Minneapolis has the highest percent of the workforce population (people aged 16 and over) employed in the country and boasts a higher GDP per-capita than Chicago, producing almost $2,000 more for every resident. A recent analysis by the Brookings Institution found that Minneapolis has fully recovered from the recession; Chicago has not.

Keys to success

1. Eliminating inefficient competition

Northeastern Illinois municipalities have a bad habit of giving away tax revenues to lure businesses to move from one suburb to the next or from a suburb to the City of Chicago, because they believe it will grow their overall tax base and create jobs locally. But this is often done without assessing the overall economic impact to the region and the effect is only a relocation of jobs, not net new job growth. Businesses are at an advantage because they know communities will compete for them.

The Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning finds that in the Chicago region, “Local governments are spending or committing significant amounts of incentive dollars to firms that may generate sales tax revenues, but have low jobs multipliers and/or low wages.” In other words, municipalities give up revenue that is supposed to go to public services or schools, and often no new net job growth is created regionally.

The agency analyzed 137 sales tax rebates and found that, for example, the average for a discount store is $3.8 million. However, one retail job supports just an estimated 0.3 to 0.9 other jobs in the regional economy and provides relatively low wages (an average of only $21,903 per year). The agency also determined that while property tax abatements may lower a bill for that particular business, the result may be higher taxes for everyone else.

In 1975 the Minneapolis region enacted the Fiscal Disparities Act so that municipalities could avoid this lose-lose competition and instead work together to grow the region. The program puts 40 percent of the growth in the commercial-industrial tax base in each municipality annually into a seven-county regional pool and then distributes those funds back to participating municipalities and school districts based on tax base and population.

The program is hailed as an effective way to reduce incentives for inefficient competition.

According to the Metropolitan Council, Minneapolis’ regional planning organization, it also “provides insurance against future changes in growth patterns—few parts of a region can count on being a regional growth leader forever and it reduces inequalities in tax rates and services.” Even donor cities—those whose contributions are shared with other regional cities—have praised the program. For example, Edina Mayor Jim Hovland likes the "trickle effect from having a strong region," while Eagan Mayor Mike Maguire says it discourages tax concessions. "We're not constantly worried that Inver Grove Heights or somebody else is going to be trying to poach those businesses and that tax base."

The City of Minneapolis has had periods where it contributes and others when it benefits. Minnesota State Representative Myron Orfield said that, “Over the past 20 years, this has reduced the gap in property-tax base between the richest and the poorest Twin Cities suburbs from 47 to 1 down to 11 to 1. By contrast the Chicago area now has a 33 to 1 disparity between richest and poorest.”

2. Education

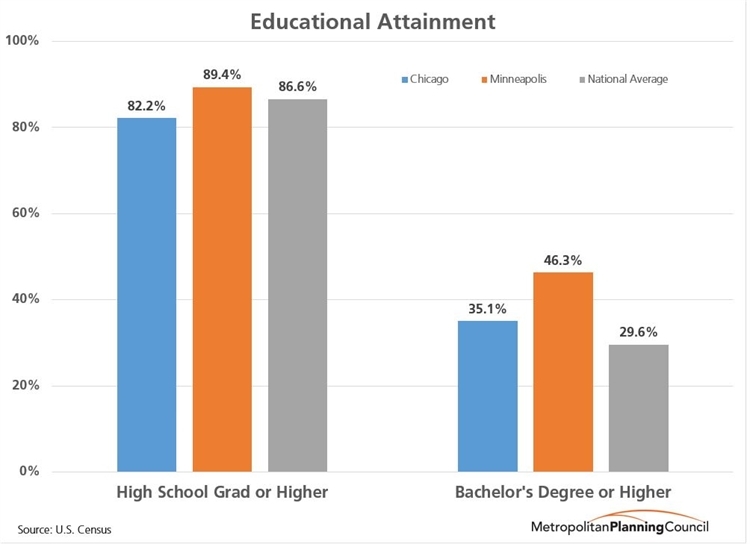

According to the Business Roundtable, “Effectively developing ‘homegrown’ talent is one of the most important challenges of our time.” Minneapolis shows how, as the Business Roundtable states, “A skilled, prepared workforce is the cornerstone of economic competitiveness.” Their low unemployment rate is linked to their educated workforce, which beats the national average and Chicago on all measures.

Talent link to job growth

According to Myles Shaver at the Carlson School of Management, University of Minnesota, this talented work pool allows business leaders to “…move from company to company within the Twin Cities, often taking best practices with them.” He also found that “all but one” of Minneapolis Fortune 500 companies “were homegrown—and that’s unique.” Shaver attributes this to a skilled labor pool that allows talent to “move from established companies to new start-ups” that are successful.

3. Quality of Life

Minneapolis consistently ranks high on quality of life indexes. Nerd Wallet recently ranked the city third in the country for quality of life, citing “ a healthy work-life balance, and a relatively low cost of living and high rates of health coverage.”

In fact, Derek Thompson writes in The Atlantic, Minneapolis is one of only three cities in the nation where “at least 50 percent of houses [are] affordable to middle-class Millennials…” and “…low-income households can work their way into the middle class and above.”

Shaver also attributes Minneapolis’ high quality of life to the reason so many businesses are successful. He finds that once talent moves to the Twin Cities, they stay there. Among college educated workers, the city has the second lowest outflow of people. “Quality of life doesn’t attract people to the Twin Cities,” Shaver said. “It keeps them from leaving.”

Transportation

Travel time to work in the Minneapolis region is 11 minutes less per day than Chicago, adding up to an extra hour a week of free time for Minneapolis workers. The city also has a widely successful congestion pricing strategy that—combined with bus rapid transit that tripled bus capacity on local interstates—speeds travel times and provides options for workers.

At 28 percent, the number of people who commute via transit in Chicago is more than double that of Minneapolis, but the City is heavily investing in new rail and bus rapid transit lines. When Mayor Rybak announced his goal to grow the City to 500,000 people in ten years, he proposed to do so “…without putting a single additional car on the street.”

Last year, Minneapolis Metro Transit saw a ridership increase of 3.9 percent system-wide. The agency notes ridership was “bolstered by population growth in the greater Minneapolis-St. Paul region and by changing transportation preferences [of residents] and expanded service.”

While Chicago remains a strong transit town—the Chicago Transit Authority saw a 4 percent increase in rail trips— there was an 8 percent drop in bus trips, for an overall decline of 2.8 percent in ridership in 2014. Chicago is investing in a new Bus Rapid Transit, called Loop Link that will speed up travel times for Loop bus riders. However, it has cut bus service over the past few years, and Gov. Rauner’s budget would cut Chicago area transit by more than $120 million. Meanwhile, Minneapolis has expanded transit with more evening and weekend bus service and a new rail line that runs between Target Field in Minneapolis and downtown St. Paul.

Minneapolis also ensures long-time residents and workers can afford to live near transit. The region’s Metropolitan Council has targeted millions in funds for affordable housing along new transit lines. Further, the Corridors of Opportunity initiative, a unique community outreach and engagement project led by the Metropolitan Council and government and business stakeholders across the region, promotes equitable transit-oriented development around transit stations to ensure people of all incomes and backgrounds share in the resulting opportunities. It funds transit-oriented development projects to catalyze weak market areas and demonstrate the potential benefit to residents of all income levels. From January 2011 through December 2013 the initiative financed seven transit-oriented developments that will create 637 units of housing (75 percent of which are affordable) near transit stations. Corridors of Opportunity also works to ensure historically under-represented people are involved in the planning process and creates tools to help finance equitable transit-oriented development.

More affordable for families?

A comparison of Census data related to changes in age of residents shows that from 2010 to 2013, Minneapolis’ population of residents aged 25 to 34, along with those under 5, grew much more rapidly than in the city of Chicago. Chicago’s older populations grew faster than Minneapolis. That could assume more Minneapolitans aged 25-34 decided to have children (the under 5 growth) and remain in the city.

This is not to say that all is rosy in Minneapolis. Of the city’s 116 census tracts, 38 are considered “Racially Concentrated Areas of Poverty." But as my colleagues Breann Gala and Marisa Novara note, “The number of Chicago neighborhoods of low and very low socioeconomic status has grown from 29 community areas in 1970 to 45 community areas in 2010.” There are 77 community areas in Chicago.

In the article "The Changing Face of the Heartland," Jennifer Bradley of the Brookings Institution reports that the Minneapolis workforce is becoming more ethnically and racially diverse, but also, "With most of the future growth in the labor force coming from people of color, it’s alarming [for Minneapolis] to have to acknowledge how profoundly the existing education and training systems have failed them." Bradley notes how important it is for the future workforce to have the skills to replace retiring Baby Boomers. For example, Hennepin County government alone has between 2,500 and 3,000 employees who will retire in the next five years. To ensure there's a large emerging talent pool, Hennepin County and other businesses are customizing training at community colleges and nonprofit educational institutions, including trainings on how to start a business.

And Minneapolis is growing, there are more job opportunities and whether they like it or not, the region’s wealthier communities give money to poorer ones, which ensures more access to opportunity for all.

In the end it comes down to what we all know makes a successful place, but is easier said than done—an educated workforce, high quality of life and growing employment. It’s circular in Minneapolis: talent drives business, quality of life keeps talent and then talent starts new successful businesses that draw more talent.

It’s also important that former Mayor Rybak set a high goal to grow the city: net growth, not growth at the sake of neighboring communities. And he wasn’t afraid to say that growth will come without more cars but with more amenities that people want, like transit.

Chicago too must set high goals. Like Minneapolis’ plan, let’s grow our population by 20 percent over the next 10 years. That would mean more than 500,000 more people to widen the tax base, ride transit and spend money at local businesses. Let’s give the 140,000 annual Chicago college graduates a reason to stay by providing them the highest quality of life in the country, by building more transit, more neighborhood amenities across the city and more affordable housing options, which all will attract more employers. And most importantly, let’s do it in a way that provides opportunities for every neighborhood in the city. We know Chicago is a world class city. Let’s show everyone else.

Read the other two posts in the series: