NASA

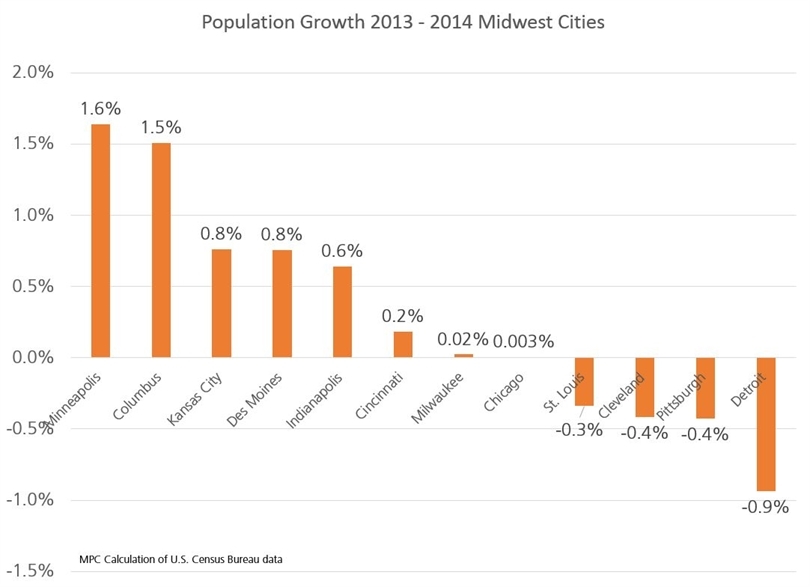

82. No, that’s not the number of your favorite Blackhawks player or the people coming to your next block party. It’s the number of people the City of Chicago gained last year. 82. Chicago’s population of 2,722,307 grew by a measly 0.003 percent. Of the top 20 most populated U.S. cities, Detroit, with a declining population, was the only city to grow more slowly than Chicago.

Is slow growth a Midwest phenomenon? It depends on how you look at it. St. Louis, Cleveland, Pittsburgh and Detroit—all former industrial Midwest cities—saw their populations decline last year. But plenty of other Midwestern cities grew at faster rates than Chicago.

The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) is getting to the root of Chicago’s population problems to find answers and solutions. The region as a whole is growing much slower than its peers, and there’s the show-off Minneapolis, which continues to place at the top. A growing population is important. More people means a larger, better-skilled labor force that generates economic benefits as they earn income and purchase goods and services, ride transit and buy or rent homes.

One answer is to change Chicago’s zoning ordinance that limits development near transit. One of the reasons people move to Chicago is because of our transit system. Google chose to relocate its Chicago office in the Fulton Market area of the West Loop because of public transit amenities such as the new Morgan Street Chicago Transit Authority station on the Green and Pink lines. According to Rob Biederman, Google Midwest public affairs & government relations manager, when deciding where to relocate, "We did an extensive real estate search throughout the entire Central Business District of Chicago…It became clear that the Fulton Market property aligned most closely with all of our needs, including access to public transportation.” And focusing development near transit is a win for the City’s budget because properties near a Chicago Transit Authority train station have almost 160 percent more value per square foot than those farther away and retain more value over time.

But as my colleague Yonah Freemark points out, there has been a decline in the share of the region’s population living near transit, even in desirable neighborhood. It’s not that people don’t want to live there, it’s that they’ve been priced out—a direct consequence of city zoning policy that limits how many residential units a developer can build. In 2013 the City passed a transit oriented development ordinance to enable more growth near transit. It was a good start, but a majority of land in the city doesn’t qualify for those incentives. Further, the law doesn’t allow mixed-use developments with a combination of retail and residential in some areas near transit—which undermines business’ desire to locate near the train. Yonah notes that even within two blocks of a CTA train station, more than half of land is zoned to ratios less than 2, which means about two stories in a dense urban neighborhood. As a result, the ability of developers to build new projects to respond to the public’s growing desire to live and work near transit is limited.

The result? We’re not making Chicago as attractive as it could be. We’re pricing people out of the most in-demand areas because there isn’t enough housing stock. So what do people do? Maybe they move to the suburbs—and if they don’t want to live in a suburb—another city.

Chicago’s transit system is one of the best opportunities to catalyze growth. More than most other places in the country, it’s one of the few cities where transit provides access to jobs and fun. MPC is working to revise local land use policies to orient them toward increased density in areas near transit, extend the Ordinance passed by the City of Chicago in 2013 and develop regulatory incentives and financing tools to encourage transit-oriented development projects accessible to people with a variety of incomes. It seems easy: Chicago has one of the best transportation systems in the country, so let’s capitalize on it to grow.