Flickr user Ken Douglas (cc)

How much parking do we really need for new residential development?

Like those of many cities, Chicago’s zoning ordinance requires off-street parking for most new development projects. These parking requirements were created decades ago with the goal of ensuring that peoples’ automobiles do not crowd the street.

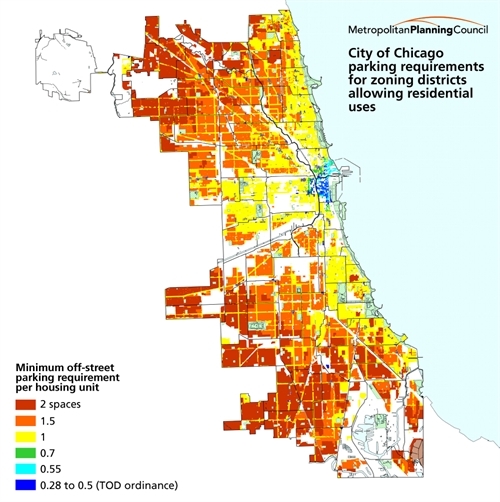

Development on more than 98 percent of Chicago land where housing is allowed must include at least one parking space per unit, and about two-thirds of that land requires at least 1.5 spaces per unit.

We’ve learned, however, that these requirements have some negative effects. Parking that is provided for free at offices increases the number of people choosing to drive to work, reducing the use of the transit system and exacerbating pollution and congestion. Parking that residential developers are required to provide with new homes increases housing costs even for those who do not drive, in essence forcing them to pay for the construction and maintenance of parking they may not even use. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) is working with the city government and partners to address this problem through regulatory reform.

Minneapolis, our growing neighbor to the north, is considering a major zoning change that would dramatically reduce parking requirements for projects being built around the city, not just downtown but also in neighborhoods throughout the city. These changes, which are currently undergoing review by the city council, would reduce peoples’ reliance on cars and lower overall household costs, particularly for those who choose not to live with a car.

The Minneapolis policy, proposed by Council Member Lisa Bender, would eliminate all parking requirements for new residential units built within 350 feet, or about a block, of bus or rail service offering frequent, all-day service (every 15 minutes at midday). Within a quarter-mile of frequent bus service and a half-mile of frequent rail service, the policy change would eliminate all requirements for buildings with 50 or fewer housing units, and reduce them to one space per two units for projects larger than that. For developments within 350 feet of infrequent bus service—coming only 30 minutes at midday—the policy would reduce current parking requirements by 10 percent.

This policy has yet to be approved, but it provides an interesting example for what could be implemented in Chicago. It would supplement Minneapolis’ existing elimination of parking requirements for downtown residential buildings and 10 percent reduction in parking requirements for developments within 300 feet of transit.

In Chicago, the Transit-Oriented Development ordinance that was passed in 2013 took a significant step toward accomplishing similar reductions in parking requirements. That ordinance eliminated all requirements for commercial or office buildings near rail transit stations, and reduced them by half for residential uses in certain districts.

The ordinance has been effective so far in encouraging new development, particularly on the north and northwest sides of the city—but today, only about 2.8 square miles of land in the city, or about 1.2 percent of the city’s land—qualifies for those parking reductions, which reduce requirements to between 0.28 and 0.5 spaces per unit (meaning 28 to 50 spaces for a 100-unit residential development).

Indeed, the following map and chart demonstrate clearly that residential developments occurring on the vast majority of land in the city still require at least one parking space per standard housing unit. Indeed, development on more than 98 percent of city land where housing is allowed must include at least one parking space per unit, and about two-thirds of that land requires at least 1.5 spaces per unit.

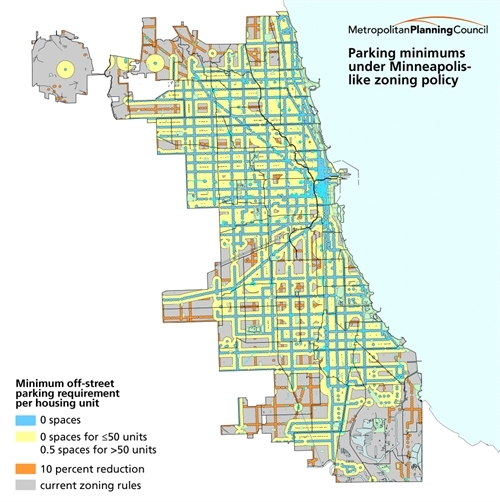

What would happen if Chicago were to alter its parking requirements to imitate those being proposed in Minneapolis?

As the following map and chart illustrate, the effects on city parking requirements would be dramatic. Because of Chicago’s very extensive frequent bus and rail network, amazingly about 20 percent of all of the city’s land is within 350 feet of a stop (shown in light blue on the map), including most of the central area and most parcels lining our city’s major arterials. These areas would, according to the Minneapolis policy, have no parking requirements whatsoever for residential uses.

Another 46 percent of the city’s land would qualify for no parking requirements for projects with 50 or fewer units and just 0.5 spaces per unit for larger buildings, as shown in yellow on the map. Because these shares also include industrial zones such as Back of the Yards, Calumet and the two Chicago airports, the vast majority of residential areas in Chicago would qualify for very significant parking reductions under a policy like Minneapolis is proposing.

It is important to note that a zoning change eliminating parking requirements is not the same as a parking maximum, which is a policy already in place for some areas of central Chicago. The changes in parking minimums proposed in Minneapolis allow developers creating new units to adapt their parking provisions to the demands of expected future residents, not to arbitrarily build parking even for people who won’t use it. In other words, developments can be customized to ensure that they are most effective for the people who need them.

There is more work to be done to determine whether a Minneapolis-style zoning change is appropriate for Chicago, or whether our city should adopt a different policy. But evidence suggests that new projects are being required to provide too much parking. For example, within a half-mile of the Chicago Transit Authority Red Line north of Belmont, 50 percent of renter households have no vehicles at all. Yet the vast majority of the land in that area requires at least one parking space per housing unit. We’re requiring the overprovision of parking, and residents are paying the cost because of it.

MPC is currently working with the City of Chicago and civic partners to evaluate how we can improve our zoning policies to foster less car-dependent and lower-cost housing options for our neighborhoods. By reforming rules that govern how developments are constructed, we can work together to improve quality of life for everyone in the city.