Flickr user John W. Iwanski (cc).

Chicagoans are packing into trains as if it were the 1940s.

Published monthly, MPC’s Talking Transit, supported by Bombardier, provides updates about transit-related activities around the world. Read In the Loop for the latest transportation headlines.

Did you know?

With 145 stations, Chicago’s El system has the second-most number of stops of any heavy rail rapid transit network in the United States after New York City. People throughout the Chicago region rely on these stations for their daily commutes and other types of daily travel. What they may not realize is that there used to be many, many more of them on the lines traveling through their neighborhoods.

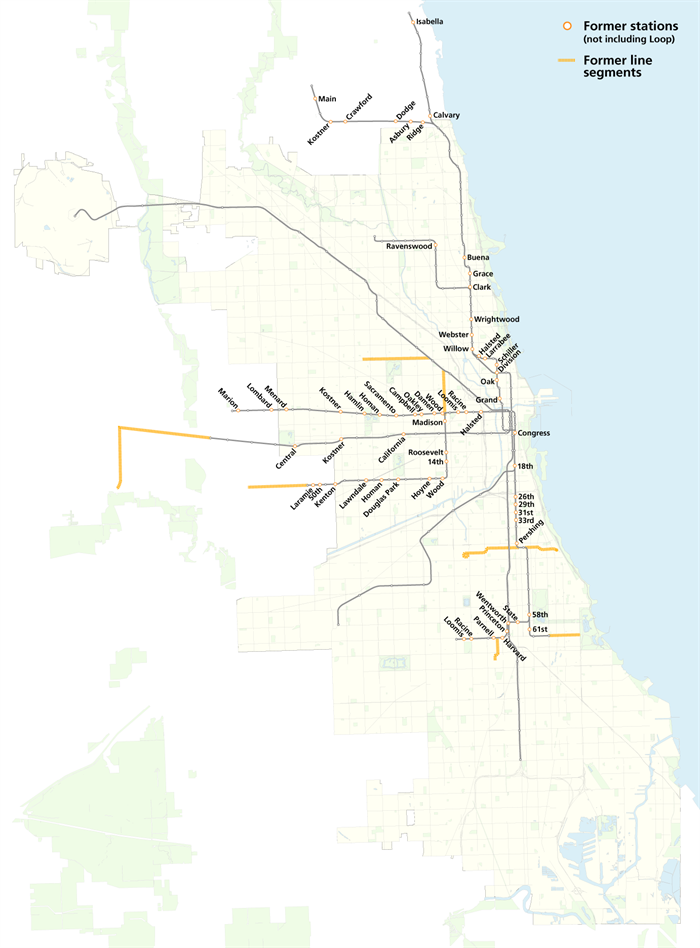

Indeed, a comparison of today’s rapid transit system with the networks that were in place in 1944 and 1957 shows that a total of 64 stations have been eliminated along lines that are still operating today. That doesn’t include dozens of stations that once operated on branches of the El that have since been torn down, including the Humboldt Park, Kenwood and Stockyards branches, among others.

Why were the stops eliminated?

The initial set of Chicago Transit Authority (CTA) rapid transit lines were constructed between 1892 and 1930 by private companies that had received contracts from the city to build the mostly elevated services. As a matter of practice, stations were generally located about a quarter-mile from one another, which, for reference, is the distance between stops like Diversey, Wellington and Belmont in Chicago’s Lakeview neighborhood.

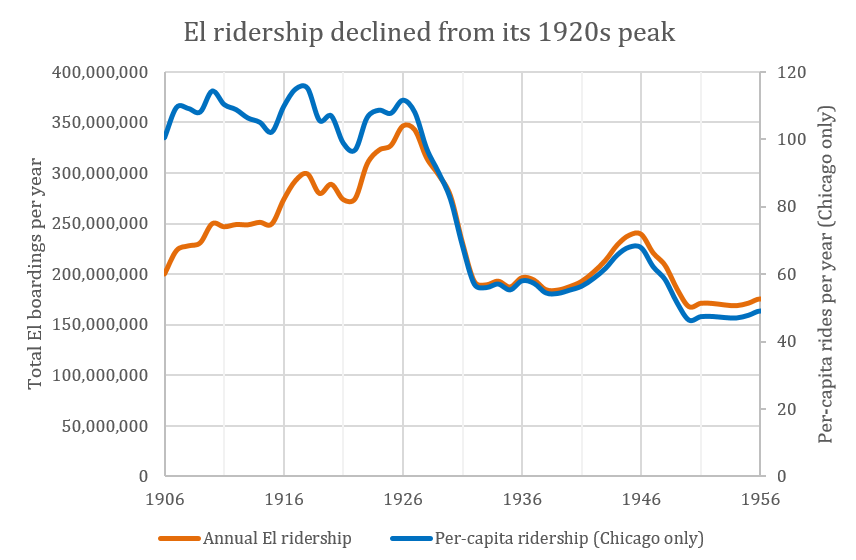

By the 1930s, the private operators suffered from a number of problems: One, they were not making much money—if any—from the services they were providing; two, both rolling stock and the physical infrastructure of the system were literally falling apart due to a failure to ensure proper maintenance. Rail ridership on the system peaked in 1926, when almost 347 million rides were taken on the lines, but it declined steadily until the early 1930s, when it plateaued, before rising due to the industrial mobilization related to World War II.

In 1945, the publicly run CTA was founded by the State of Illinois, and, because of the failure of the private companies to keep the system going, took over the city’s El and streetcar lines in 1947.

The CTA’s immediate need was to adjust service to a continued drop-off in ridership. As the region’s economy shifted away from the resource shortages that characterized the wartime period, increasing numbers of residents chose to buy and use personal automobiles and the result was a reduction in transit use. The number of boardings fell by 30 percent between 1946 and 1950, as shown in the following chart.

Data: CTA records, U.S. Census Bureau. Population adjusted based on decennial Census estimates; rail ridership adjusted to include station entries only, not cross-platform transfers.

CTA’s approach was a massive cutback in stations and services. As documented by Chicago-L.org, starting in 1948, the authority eliminated service on the Skokie branch, then soon after, the Westchester, far Douglas, Humboldt Park, Normal Park, Stock Yards, and Kenwood branches. (The Skokie line was later resurrected as the Yellow Line.) Due to low ridership, stations all around the city were closed, in many cases increasing the distance between stops from a quarter-mile to a half-mile or even, in some cases, a full mile.

At the end of 1957, the system was in many ways a shadow of its former self.

As the following map shows, CTA branch lines that once served communities on the South and West sides were eliminated. And stations all over the system on existing lines were eliminated in the name of cost cutting and the reality of serving a shrinking transit-riding patronage. Though most of the stations were closed in the late 1940s and early 1950s, additional stations were closed on the Blue Line along the Eisenhower Expressway (such as at Kostner in 1973, just 11 years after it opened) due to limited use, and others were closed on the Green Line after its reconstruction in the mid-1990s (such as at Racine).

All along the routes of the El, Chicagoans can still identify remnants of former stations.

Side effects of fewer stations

Though the removal of stations along many of the El lines reduced access for many communities through which rail services run, reducing the number of stations along lines does have some positive benefits.

For example, manning a station and keeping it in good condition requires annual operating expenditure. Given the limited funding for transportation, maximizing expenditures on only the most important services must be a priority for agencies like the CTA. Because stations were so close to one another before removal commenced, in most cases, there still isn’t that much distance between stops, which means most people have the ability to walk to nearby stations.

In addition, removing stops speeds transit service. By allowing trains to run longer distances between stops, average travel times for many people using the system were reduced when station elimination occurred. By reducing the travel times of trains from end to end of lines, CTA is also able to reduce operating expenditures by needing fewer trains operating on a line at the same time.

Is it time to consider adding stations again?

Even so, there is reason to believe that, in some cases, adding new stations to the existing lines has its merits.

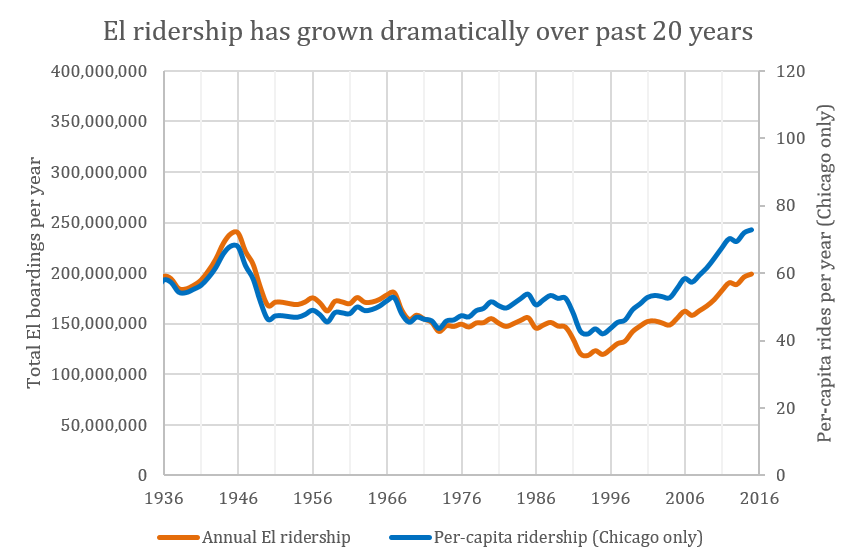

For the past 20 years, as the following chart demonstrates, ridership on the El system has been growing at an almost constant clip. As of 2015, boardings are the highest they’ve been in any year since 1948 (shown in orange). And on a per-capita basis (trips per average Chicagoan), ridership growth has been even stronger (shown in blue). 2015 had the highest per-capita El ridership since 1930, with the average Chicagoan taking 73 rides per year.

It is worth emphasizing that overall per-capita transit use in Chicago—including bus riders—is significantly lower now than it was in 1980. As I documented last year, while per-capita transit ridership in Chicago was equal to that of New York in 1980, Chicago’s per-capita figure is now 37 percent lower than our East Coast peer. But Chicago’s bright spot is our El system, which continues to grow in popularity every year.

MPC’s work on transit-oriented development has demonstrated that people living and working near rapid transit are much less likely to commute by driving. In the city of Chicago, 46 percent of people living within a quarter-mile of El stations took transit, walked or biked to work—versus just 26 percent of those living further than a half-mile from El stations.

Building additional stations on current lines can play an important role in adding accessibility to the transit system, which, in turn, can bring more people onto the transit network every day.

The recent openings of the Morgan Station in the West Loop (in 2012) and the Cermak-McCormick Place Station in the South Loop (in 2015) demonstrate how new stations on existing lines can be helpful. Both sit on sites where stations were once located but were eliminated (the stations were originally closed and demolished in 1948 and 1977, respectively).

Now, both are attracting significant surrounding new construction, and all indications suggest that they’re adding to overall transit ridership, not taking away from other services.

It’s been almost 70 years since the CTA took command of Chicago’s El system, and the network is in a decidedly different condition than it was then. Rather than declining ridership and poor maintenance, the El has experienced rapid growth in boardings and the CTA has improved the system’s infrastructure considerably. Now perhaps it’s time to bring back more of those old stations.