Flickr user Disco Palace (cc).

A rezoning proposal by the City of Chicago would increase the potential for construction in the West Loop.

Earlier this week, the Mayor’s Office of the City of Chicago introduced an ordinance that, if approved by the City Council, would significantly expand the reaches of the downtown area, increase funding for commercial and cultural needs in low-income sections of the city and simplify the development process.

These changes, which the city’s Dept. of Planning and Development has detailed, would represent one of the largest “upzonings” in Chicago’s history, adding significant new space for the city to grow.

Understanding the proposed zoning change

The proposal released for aldermanic consideration could and probably will be revised as it is being reviewed by the public over the course of the next week, but as it stands, the “Neighborhood Opportunity Bonus,” as the City has entitled it, is interesting and worth evaluation.

This zoning reform has three main principles:

One, it would replace 20 existing rules that allow developers to increase the size of their buildings downtown (the bonuses are not currently in effect outside of downtown). These bonuses currently provide builders the right to build larger buildings (in the form of an increase of floor area ratio, or FAR) in exchange for providing amenities such as green roofs or winter gardens.

The reform would eliminate those bonuses and replace them with a single pay-to-expand system that would allow developers to pay the City in exchange for the right to build larger. They would be able to pay more, up to a certain point, for each additional square foot of space they want to build.

Two, the reform would direct money raised through the above process into three funds. Eighty percent of money would go to a new Neighborhood Opportunity Fund designed to support commercial and cultural developments in underserved parts of the city, primarily on the South and West sides. Ten percent would go to landmark building renovation and 10 percent would be directed to public benefits downtown within a half-mile of new construction, such as better transit or river walks.

The net effect would be a redirection of city funds to areas of the city that have experienced underinvestment for decades. The Metropolitan Planning Council (MPC) agrees with this focus on investing in retail and other amenities in lower-income portions of the city, and it was one of the primary conclusions of our 2015 report, Grow Chicago.

Though it is insufficient, Chicago has financing available for affordable housing in underserved communities. There aren’t nearly as many tools like that available for retail or commercial needs, however, to balance it out between booming areas and underinvested ones.

Three, the downtown zone itself—the areas where the “D” zoning designation is in effect—would be expanded north, northwest, west and south, further into River North, the West Loop and the South Loop. Developments in these areas would be able to benefit from the new bonuses described above and, in many cases, would be able to be larger than currently allowed as their current zoning classifications would be replaced with downtown zoning classes.

Responding to demand to live and work downtown

This zoning reform responds to the reality that the city of Chicago’s growth over the past few decades has been concentrated downtown. The center of our region is the area where public demand is focused, and it’s the area where the city has the greatest opportunity to grow.

Between 2002 and 2014, more than 90 percent of the city’s job growth, or 86,322 of the city’s overall 94,270 new jobs during that period, were located downtown, according to an analysis of data from the Census’ On The Map. Though developers have responded through the construction of new buildings such as at Wolf Point, this growth in jobs suggests that more development is needed to accommodate future jobs.

Moreover, the city’s population growth has been focused in the center city. Despite a loss of almost 200,000 residents between 2000 and 2010 in Chicago as a whole, downtown and the surrounding neighborhoods gained tens of thousands of people. For our region to grow, it is essential to respond to this demand, and this zoning reform does so.

Major impacts

An MPC review of the proposed zoning reform suggests that it would dramatically impact development potential in the areas where the downtown zone would be expanded.

In the four areas where the downtown zone would be expanded outside of today’s downtown, about 20.1 million square feet of developable parcels would be affected by the zoning change (this figure excludes open space and transportation facilities). Of these parcels, about 1.9 million square feet is currently vacant or simply holding parking, according to land use data from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning, indicating that they’re ripe for redevelopment in the near term.

MPC conducted an analysis of the proposed zoning reforms to determine how much they would impact development potential in the expanded downtown zones. The analysis focused on the 11.9 million square feet of parcels not currently zoned as Planned Developments or Planned Manufacturing Districts. These areas would be affected by the reform but are difficult to compare because development restrictions imposed on them are customized by the parcel through a special zoning review process.

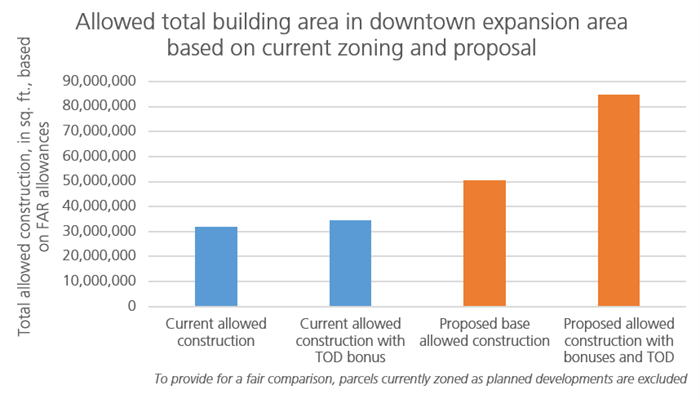

As the following chart shows, on the parcels where the downtown zone would be expanded, current law allows between 32 and 35 million square feet of development, depending on whether developers take advantage of the provisions of the recently passed TOD Ordinance.

With the zoning change, new development in the area would be dramatically encouraged by increasing the potential for new construction in the area to 50.6 million square feet of built space, or a 58 percent “upzone”—a term to describe a regulatory reform that allows more construction than previously permitted. If developers take advantage of the full zoning bonuses included as part of this reform, the development potential in this area would increase to 84.7 million square feet, or a 165 percent upzone.

That’s the equivalent to adding the developable space of almost 12 new Willis Towers—likely enough capacity to accommodate the growth of the city of Chicago in the coming decades. And that figure does not include changes in zoning affecting the aforementioned Planned Development or Planned Manufacturing District areas.

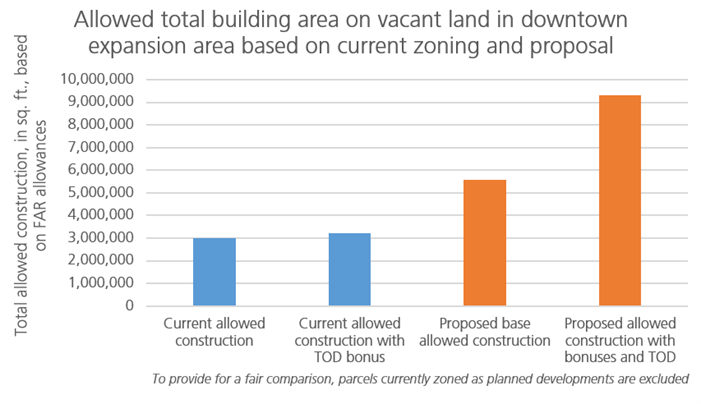

Just looking at land that is currently vacant or used as parking, the zoning changes proposed by the City of Chicago would provide for significantly more construction than currently allowed, increasing the buildable development potential from about 3 million square feet to almost 6 million square feet with no bonus or more than 9 million square feet if developers take full advantage of the bonuses that would be provided to them.

For context, that’s the equivalent of providing extra space for between 2,400 and 6,100 new units of housing.

MPC supports efforts to expand development in in-demand areas like the center city, where quality transit options are available. In addition, new funding for neighborhood retail and commercial needs will play an important role in improving quality of life for disinvested neighborhoods in the coming years.