Alden Loury

The CTA bus terminal on Western Avenue near 79th Street. In the 1980s, the author observed Western Avenue as an unofficial boundary between black and white Chicago.

This article originally appeared on the Social Justice New Network.

One of my enduring childhood memories, growing up in the 1970s and 1980s on Chicago’s South Side, was something I called the “boundary.”

At that time, the boundary was an imaginary line along South Western Avenue separating the neighborhood where I spent most of my childhood from the neighborhood to the west. The boundary was clear and distinct because of one unmistakable fact: the people were black on my side of that boundary, and they were white on the other side.

This is me in 1978

Travelling along 79th Street, I remember crossing the boundary quite often as a child accompanying my mother on routine trips to the Evergreen Plaza, Scottsdale and Ford City shopping malls among other destinations. Whenever we crossed Western Avenue, I knew things were different.

The houses were bigger, the lawns were prettier, the cars were fancier, and the streets were cleaner. As a result, I presumed that the people there were happier and wealthier.

The sun even seemed to shine brighter on the other side of that line.

I wasn’t surprised by the boundary, having heard my mother—a Chicago native herself who came of age during the 1950s and 1960s—talk about segregation. She’d told me that Damen Avenue served as the boundary when she moved us to the neighborhood in the early 1970s.

Even with that knowledge, the boundary’s presence still had a profound impact on me.

After dozens of trips back and forth across that imaginary dividing line, witnessing the same characteristics over and over again, those observations became more than just youthful perceptions of the world around me. What formed was a firm picture of reality—a stone cold truth etched into my psyche.

I concluded, quite simply, that life was better where the white people lived.

It’s an understanding held by many Chicagoans, young and old, I believe. It’s a reality reinforced by living in a metropolis with dozens of invisible color lines that have separated racial groups, particularly blacks and whites, for decades. People on either sides of those boundaries, including folks who’ve never actually ventured across them, consider the presence of white people to be an indicator that a neighborhood is safe, prosperous and “better,” while the presence of black people indicates the opposite.

That picture was crystallized for me in stark terms when I actually saw a visual representation of the boundary, as I remembered it, for the very first time.

The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates used Chicago as the backdrop for his provocative June 2014 cover story, “The Case for Reparations.” In it, he artfully weaves Chicago’s history of segregation through a timeline of the American government’s plundering of black wealth from slavery—through Jim Crow, decades of racist housing policies and separate-but-equal realities—to this very day.

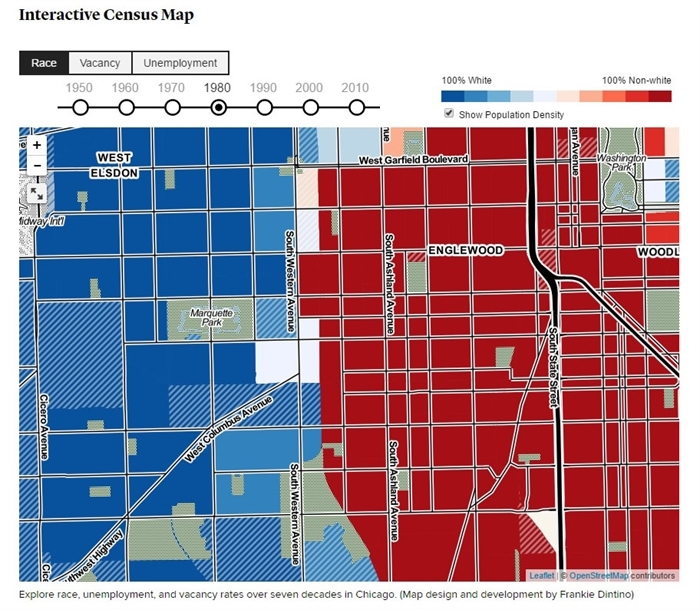

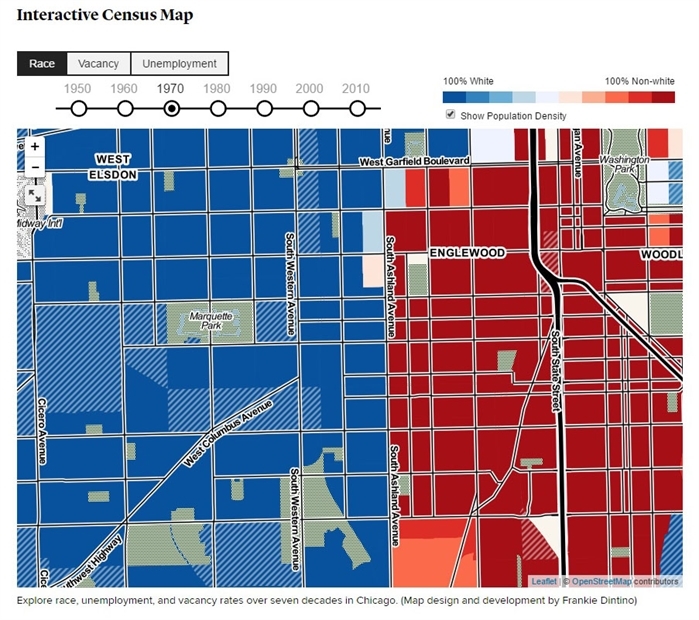

To highlight Chicago’s segregation, The Atlantic included interactive online maps of the Chicago region that tell their own powerful story—vividly illustrating the boundary I remember as a child and uncovering dozens more of which I’d never known.

The maps provide snapshots of the racial demographics of census tracts in the Chicago region—depicting their levels of white and nonwhite population (shown in hues of blue and red, respectively)—for each decade dating back to 1950. The maps also provide options to view vacancy and unemployment rates. (Explore the maps by going to “The Case for Reparations.”)

I zoomed in on the 1980 map to see the deep red just east of Western Avenue and the dark blue to the west. It was a colorful, bird’s eye view of the contrast I remembered from my childhood: black on one side and white on the other.

In 1980, the border between black and white was at Western Avenue.

I studied the maps for the preceding decades and quickly realized that the boundary had existed long before I’d recognized it as a child. Not only had racial dividing lines existed for decades, but they moved, rapidly shifting to the east, west and south from the historic Bronzeville community where hundreds of thousands of African Americans had settled during the first half of the 20th Century.

In 1970, the border between black and white was a mile east, at Ashland Avenue.

Through the years, the boundary I remember as a child has gradually shifted farther west extending beyond Western Avenue in 1990, Kedzie Avenue in 2000 and Pulaski Road in 2010. What was almost completely dark blue in 1950 is nearly all red in 2010. With the emergence of Latino communities on the southwest and southeast sides and the continued expansion of African-American neighborhoods, nonwhites now dominate a South Side where they were practically non-existent half a century ago.

All the while, the maps clearly show that the racial dividing lines remain, displaying varying shades of red on one side and blue on the other. Collectively, the images lay bare just how intertwined racial segregation is with the history of Chicago.

The stark contrasts between dark blue areas of whites and deep red areas of nonwhites reveal that racial segregation is as much a part of Chicago’s identity as the city’s iconic skyline, harsh winters and deep dish pizza.

In convincing fashion, the maps also show that Chicago’s segregation is no accident and that these boundaries don’t emerge as happenstance. Their persistent presence and continually shifting nature illustrate that Chicagoans are deeply aware of these racial borders. They’re not at all invisible.

Generations of black folks have come to the same conclusion I reached as a child, actively seeking to cross those racial dividing lines in search of a better quality of life. And generations of white folks have responded by moving elsewhere.

Sure enough, the racial turnover doesn’t occur today as rapidly as it did 50 to 60 years ago, but it still occurs. As a result, South Side areas that are racially mixed today will probably be predominantly black at some point in the near future; you can put money on it.

These racial boundaries uncover our deepest beliefs about the areas where black people live and the areas where white people live. Those ever-changing borders are perhaps the clearest signs of how little progress Chicago has made with its eternal struggle with segregation and the underlying assumptions and fears that drive black people to cross those boundaries and white people to establish new ones.

And make no mistake about it, regardless of whether the fears and assumptions are warranted or true, their impact is dramatic. The identification of a community as a “black” neighborhood has serious, real-life consequences for its residents.

As Chicago communities change from white to black, their opportunities for major investment—from both the private sector and public sector—begin to evaporate. Retailers and developers have to ask themselves if it’s worth it to build in mostly black areas, knowing that they’re unlikely to attract white shoppers or residents. As evidenced by those shifting racial dividing lines, today’s African-American communities in Chicago are ill-equipped to compete for housing, economic development and other resources or amenities, in part, because they’ve been written off by whites.

This is me in 1987

Interestingly, the characteristics that I witnessed in the 1980s when I crossed that racial boundary are practically the same today; I returned to my childhood community in 2005. Now when I travel along 79th Street and cross Western Avenue, I see the same differences in homes, cars, and quality of life that I witnessed decades ago. But now the people living in what I’d always considered to be a “better” neighborhood are black.

It’s refreshing to see.

Perhaps, if the white folks who lived there during my childhood had stuck around long enough, they would’ve realized that they didn’t have to fear the arrival of their new black neighbors. Nearly 30 years ago, when African Americans first began moving to the area, they probably had more in common with their new white neighbors than they did with the people in the communities they left behind.

And since it appears that many of those black folks have stuck around, maybe they’ve realized that they don’t have to flee at the first sign of unrest or disinvestment. The mass exodus of stable black families—in search of “better” neighborhoods—is a contributing factor to the decline of some black communities. After all, my childhood neighborhood was, at one time, considered a prime destination for African Americans in the 1960s and 1970s, until the white communities to the west showed greater promise and drew black folks farther west—kicking off the next cycle of shifting racial boundaries.

But I’m just kidding myself.

Those colorful maps and their evidence that our racial boundaries still exist are sobering reminders that we’ve still got a long way to go before we realize that we don’t really need those borders at all.