Imagine a transit system with no turnstiles and no fares. Photo courtesy of the CTA.

Tweet this

In March, MPC held a sold-out Urban Think & Drink with Jahmal Cole, founder of My Block, My Hood, My City, to discuss how we might break down the barriers to equity in our region. During the event, Cole made a provocative statement that has sparked a discussion: the CTA should be free. As noted elsewhere, the potential benefits are huge. Reducing barriers to mobility would create new opportunities to work, play, and live for millions of Chicagoans. Making transit free could get more people out of their cars, improving local air quality and reducing the city’s greenhouse gas emissions. There’s even a strong business case. Free transit would draw more people to the city, deepening our pool of talent and expanding the local customer base.

But what exactly would it take to provide free CTA service? The CTA can’t just operate without revenue, after all. It’s a complicated question, and it depends on the approach taken to subsidize the service. For instance, are fares still collected and then later reimbursed? Are fares eliminated entirely? Are they eliminated for residents, but visitors and tourists still need to pay? In any scenario there are some major legal hurdles that would need to be cleared first. Getting something like this passed would require a clear vision, very broad public support, very strong political champions, and as much as $580 million in new annual revenue to offset the cost.

Is it even legal?

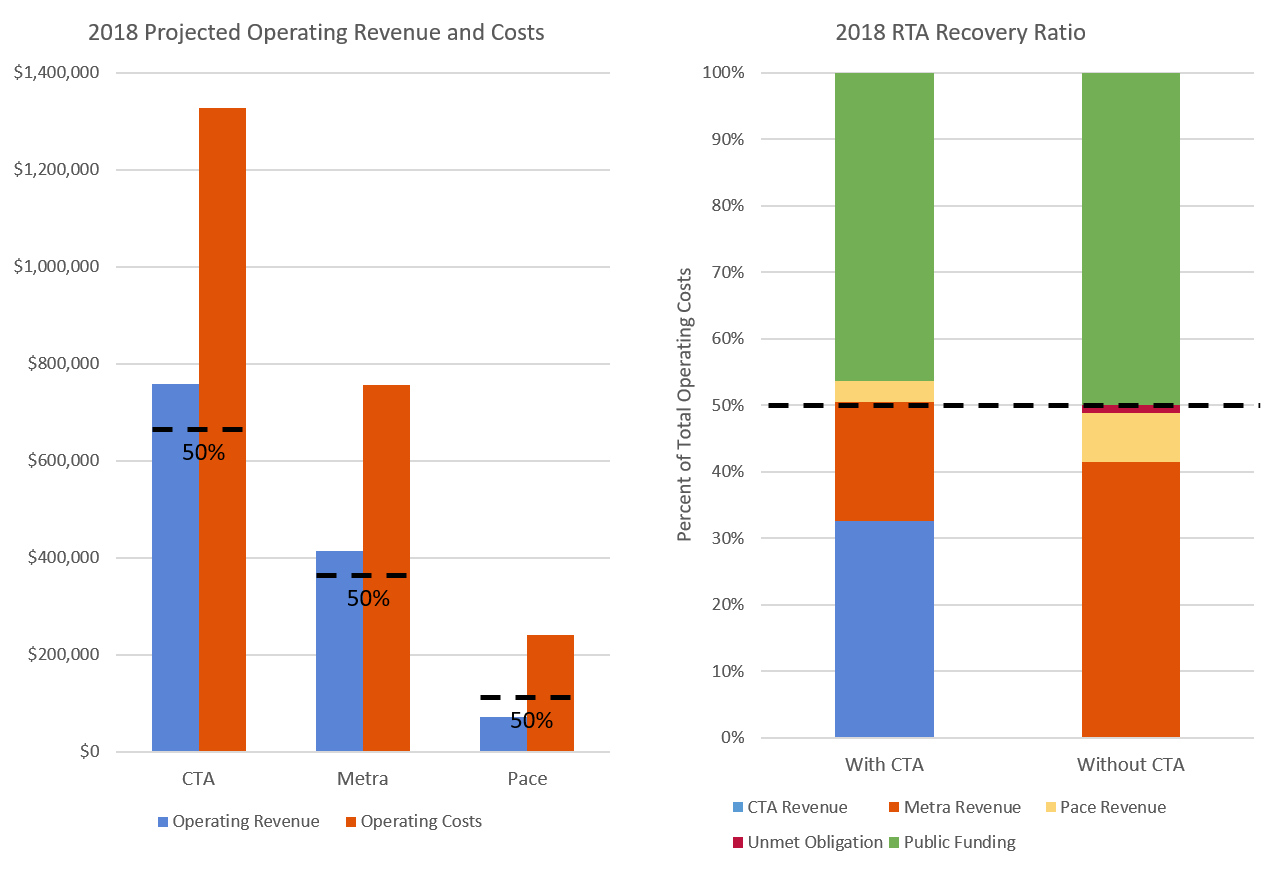

Currently, a fare-free CTA is not exactly legal. The most immediate hurdle is the Regional Transportation Authority Act. The RTA Act specifies the structure, responsibilities, and finances of the RTA, which is the oversight body for Northeast Illinois’s three transit agencies (CTA, Metra and Pace). Critically, the RTA Act mandates that the three agencies must recover at least 50% of their combined operating costs through system-generated revenue (fares, passes, ads, vendors, etc). This is called the recovery ratio. The first step toward a free CTA could be to amend the RTA Act to decouple CTA’s finances from Pace and Metra, and exempt CTA from the 50% recovery ratio requirement. Doing this in isolation from Pace and Metra could be challenging. The three transit agencies have very different revenue generating capabilities, and CTA (the most profitable) helps pad the total.

Click here for a closer look at the following charts.

The RTA has the power to set specific recovery ratios for each agency on an annual basis. In 2018, both CTA and Metra are expected to recover well over half of their operating costs. Pace’s requirement is lower because the cost of operating suburban bus service is disproportionately higher. Having CTA and Metra’s recovery ratio above 50% allows the combined ratio to still meet the statutory requirement. If CTA’s operating revenue and cost were removed from the 2018 budget, there would be an $11.7 million gap Metra and Pace would have to make up to satisfy their legal obligation. That might not sound like a lot, but if CTA service became free, we could expect a significant shift in ridership away from Pace and Metra, making that extra money hard to find. It would be a tough sell to those outside the CTA's service area.

How would we pay for it?

Whether or not the RTA Act is amended, the revenue lost by providing free CTA service would need to be replaced. For the past several years, the CTA has collected about $580 million in fares. This could be replaced by increasing existing sources of public funding, or by creating new ones. There are currently three significant sources of public funding: the RTA sales tax (about $440 million a year), the Real Estate Transfer Tax (or RETT, which totals about $65 million a year), and the Public Transportation Fund (a state-provided match on a portion of sales and RETT tax collected in Cook County, totaling about $80 million a year). Unfortunately, the state has been chronically late making PTF payments for several years. They now owe the RTA $485 million, forcing the agency to issue millions in short-term loans to cover the gap and adding even more uncertainty to an already tenuous position. Cash flow woes aside, how exactly could $580 million be raised to cover operating costs? Increasing the sales tax in Chicago by 1 to 2% might be enough, but it would put the city’s combined state and local sales tax rate at about 11 to 12% - among the highest, if not the highest, in the nation. The Real Estate Transfer Tax likely couldn’t be increased to the point that it made a major contribution. Extracting such a high cost from existing sources of transit funding seems unlikely.

MPC has investigated many alternative revenue sources as part of our efforts to advocate for sustainable transportation funding in Illinois, such as increasing the motor fuel tax and expanding the sales tax to services. A mixture of these sources could potentially cover the lost revenue from a fare-free system. However, it’s impossible to have an operating revenue discussion without also considering capital costs. The RTA has estimated the existing capital funding shortfall for the Northeast Illinois transit system to be in the neighborhood of $2-$3 billion annually. This is the money needed to simply stop the degradation and bring existing infrastructure into a state of good repair (currently 31 percent of the system is not in a state of good repair). By eliminating fare revenue, the CTA would need to raise an additional $580 million on top of the billions needed annually to fix current infrastructure. That’s not to say it can’t be done, but it’s imperative to avoid a situation that results in further deferring maintenance needs, putting us on the road to becoming the next MTA or Washington Metro.

Has it been done before?

There are a few examples of cities that provide free transit service, and many others that provide limited free service on one or two routes, or within a limited zone. The most famous case is Tallinn, the capital of Estonia (population: 450,000), which provides fare-free transit for all residents. The system was already heavily subsidized when it became free and is largely financed through an income tax. Visitors still pay to ride. Other smaller overseas systems are partially or wholly free, but those countries generally have a much healthier appetite for taxing themselves. An example closer to home is Chapel Hill, NC, which offers free fixed-route bus service. That system has an annual budget of about $20 million, an order of magnitude smaller than Chicago. It’s paid for by the surrounding municipalities, and very healthy contributions from the University of North Carolina. In Pittsburgh, free trips are provided between 6 adjacent light rail stations that take people from downtown to the city’s stadium district. This is funded through a partnership with the Steelers and the Rivers Casino, but it has a very limited geographic scope and bus service is not included. Kansas City has a single free street car line that runs just 2 miles through downtown. Salt Lake City has a free fare zone in its downtown, but any rides originating or ending outside of the zone require payment. These are fairly typical examples of the limited free transit options in the US. Needless to say, a free CTA would be the most ambitious project of its type in the Western Hemisphere, and probably the world.

Is it worth it?

There are many ways free CTA service could benefit not just Chicago, but the whole region. It could incentivize more transit-oriented development, reducing sprawl and the inflated infrastructure spending that goes with it. Given that transportation is the largest contributor to climate change in the US, it could be a powerful local strategy to reduce greenhouse gas emissions. There’s also an obvious equity argument. Approximately 71.5% of CTA ridership qualifies as minority, and 29% qualifies as low-income. Eliminating fares would be a powerful tool to improve mobility and access to opportunity for these populations. As MPC’s Cost of Segregation report showed, reducing income inequality and segregation in our region would have a massive impact on us all.

Paying for it would require creativity. But if there’s a political will, there’s a way. If we could show that the system would pay for itself by attracting new residents, boosting the economy, cleaning up the environment, and reducing inequality, we might just convince people that it’s worth paying for. MPC always encourages Northeast Illinois to think big and look for innovative solutions. Making transit even more accessible to riders could distinguish Chicago as a place that has doubled down on investing in a high quality of life for all.